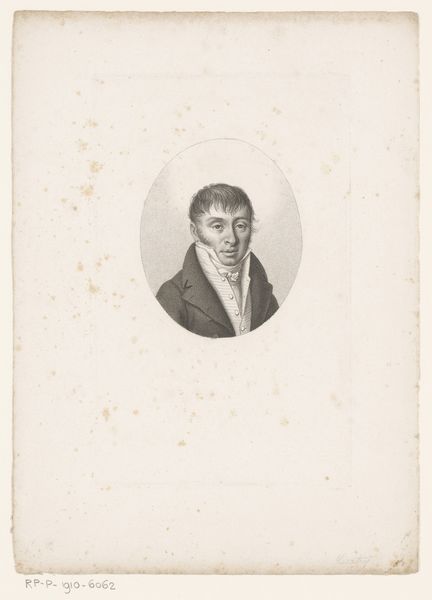

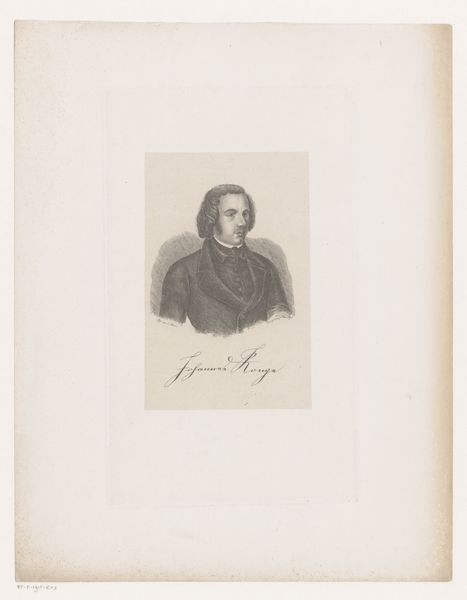

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 97 mm, width 89 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

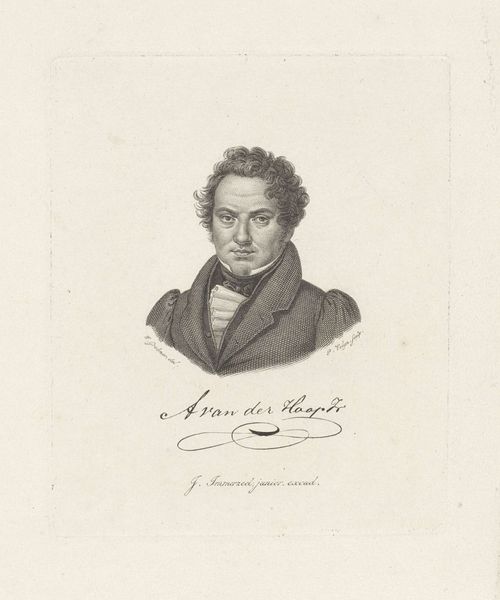

Curator: Here we have Heinrich Lödel's print, "Portret van Gustav von Hugo," created sometime between 1808 and 1861. The technique is engraving, typical of that era. Editor: He looks...intense. The man in the picture, I mean. There's a directness in his gaze, and the engraving gives it this lovely, almost ethereal quality. What was the process like to produce such engravings? Curator: Engraving involves meticulously carving lines into a metal plate, applying ink, and then transferring the image onto paper. It's a labor-intensive process, demanding a high level of skill and precision. I wonder what it tells us about value – labor of that kind. It must have seemed luxurious, despite its increasing affordability with mechanization. Editor: It does speak volumes, doesn’t it? Imagine the countless hours Lödel must have spent, carefully etching each line to capture Von Hugo’s likeness. It elevates the status of both artist and subject, in a way only achieved through such devoted craftsmanship. Makes you think about all that invisible effort behind images even then... were portraits often intended for mass production? Curator: Absolutely. While initially the preserve of the elite, advances in printmaking allowed images like these to circulate more widely, influencing popular perceptions and shaping cultural narratives, a powerful thing really, the shift of representation from singular paintings to a more dispersed image. How it echoes today, even. Editor: Looking at the details of his clothes, the way they’re rendered with such precise lines, speaks of the importance attached to materiality back then. Did Von Hugo, or his family, commission the portrait, and was it about prestige, displaying their wealth? What does the availability of reproducible images do to ideas of individual value, though? Does this impact Lödel’s commission and status? Curator: No easy answers to such questions. What this piece awakens in me is not the weight of history or the sweat and grime of labour; but a question of humanity—who was Gustav, what did he think, what was the world he hoped for? Editor: But Gustav existed within a particular social framework that Lödel had to navigate. Their relationship, even in reproduction, impacts how we interpret it all. But what did these portraits signify within that cultural landscape? And how do you, as an artist, reconcile that materiality, that process, with the subject and its emotional core? Curator: That, my dear friend, is the tightrope every artist walks: honoring the grit while seeking the stars. Now I must say, thinking of this piece has shifted something within me. The process suddenly seems alight with human potential.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.