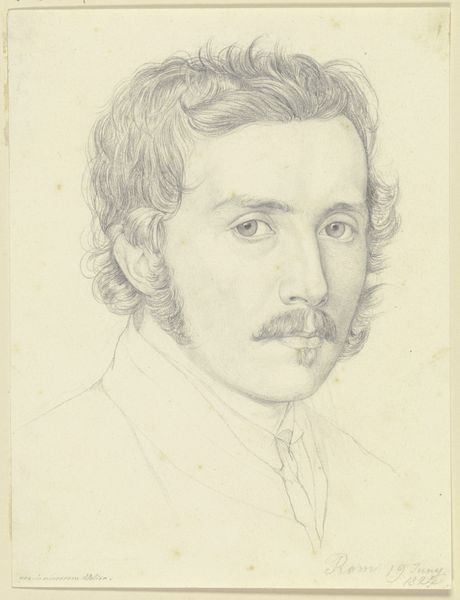

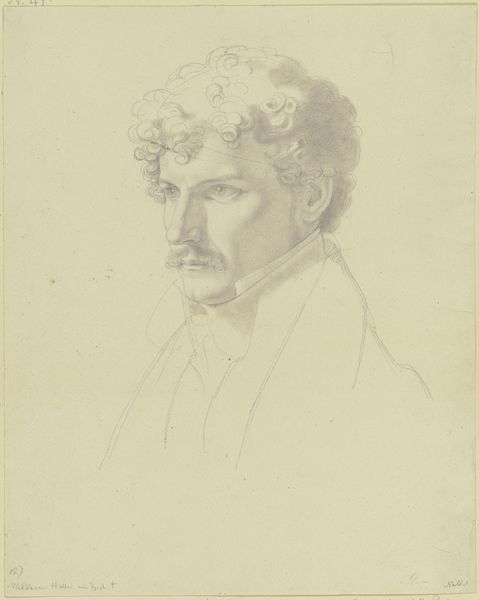

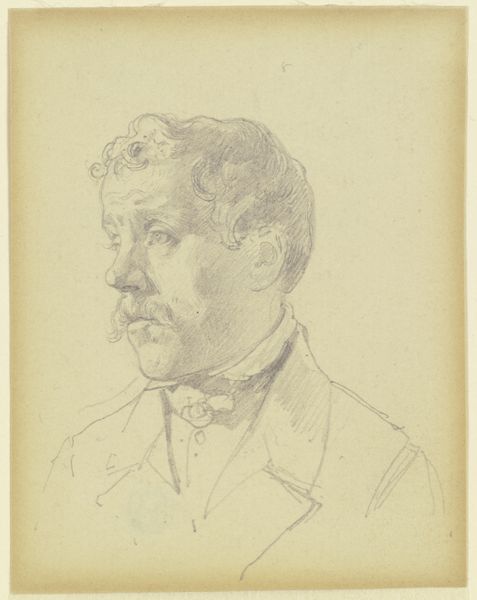

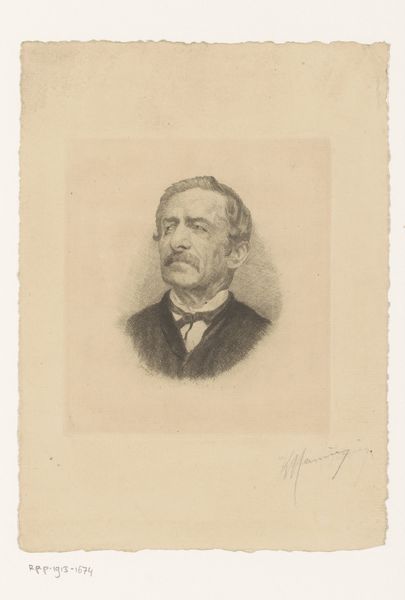

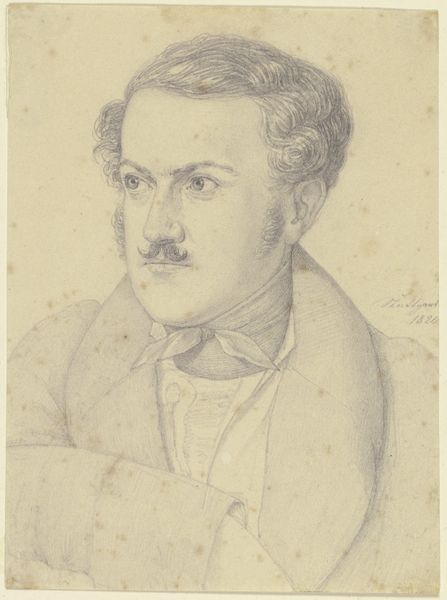

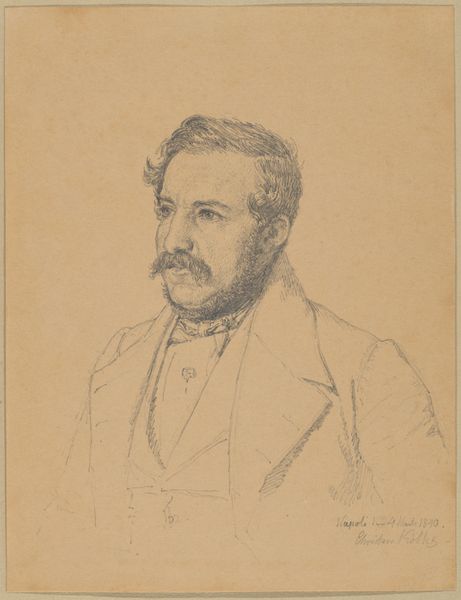

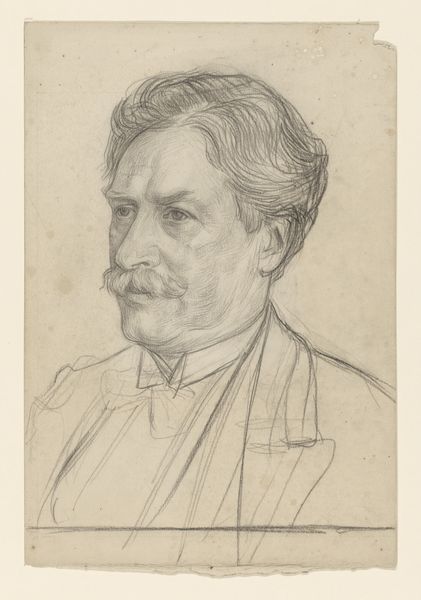

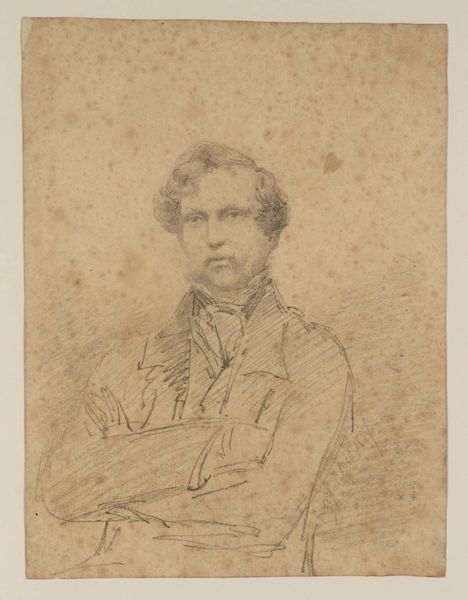

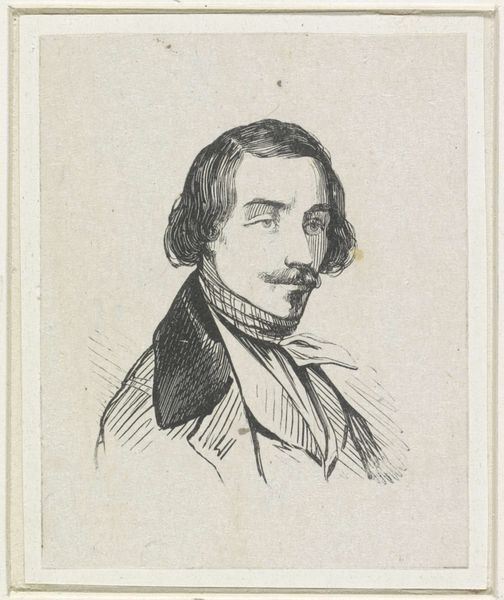

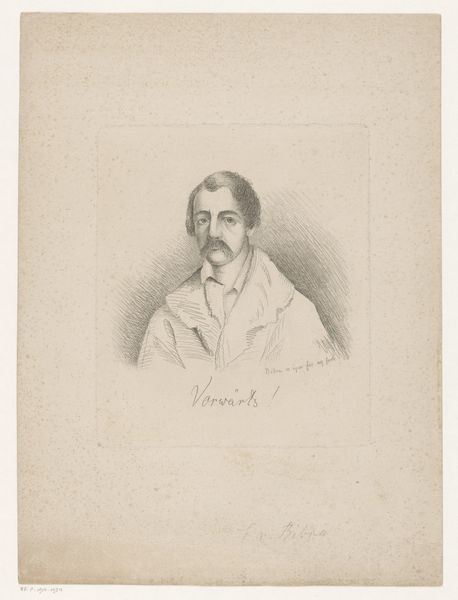

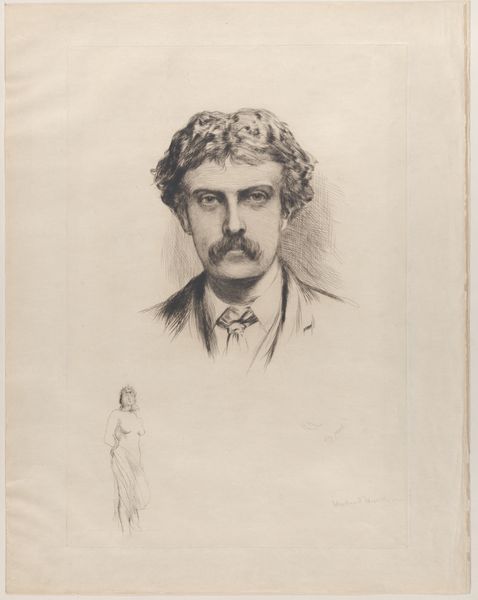

drawing, pencil

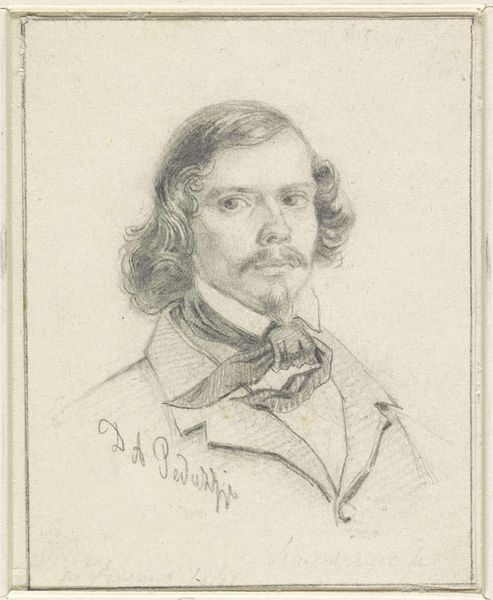

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

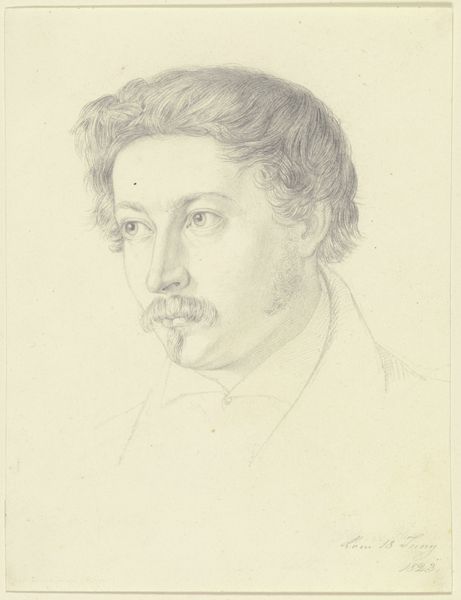

self-portrait

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: sheet: 13.2 × 10.5 cm (5 3/16 × 4 1/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Looking at this drawing, one is immediately struck by the artist's focused gaze and evident attention to detail. It's Eastman Johnson's self-portrait, dating from around 1850, rendered with delicate strokes of pencil on paper. What are your first impressions? Editor: Immediately, I think of a daguerreotype trying to break free from its own stillness. It’s so intimate, this self-examination frozen in graphite, but there's a fragility that transcends mere technical skill. Curator: Exactly. Consider that the mid-19th century was a time when the burgeoning middle class increasingly demanded portraiture, but outside formal painted commissions, drawings allowed artists to explore their identities more freely. This piece certainly conveys such exploratory intimacy. Editor: You can almost feel Johnson wrestling with his self-image, translating himself for the world. I see it in the contrast between the sharply defined eyes, full of self-assuredness, and the more vaguely rendered clothing, as if the outer trappings were less important than his inner essence. He doesn’t portray a persona, only the person. Curator: Right. Beyond this, it is also an exploration of light. Academic art demanded facility with line and value, and Johnson shows his mastery. How interesting that a style so connected to established institutions can become a site for revealing vulnerable, interior thoughts. Editor: Perhaps the rigid techniques become tools to really reveal that vulnerability? Like holding a mask up close, so you see every pore, every crack. Makes you consider the public role of the artist, their participation in society and how their intimate, interior expression plays with, or against, that. It's interesting to note he did a few images reflecting racial tension... Did that make him self-reflect more acutely do you think? Curator: It's tempting to imagine this drawing as preparation for later, more recognized portraits; a working-out of light and form. But it might be more than just study. Looking at those soft pencil lines constructing bone and muscle and doubt...it feels more akin to philosophical quest, if you ask me. Editor: Absolutely. And like all the best self-portraits, you begin by seeing the artist, and end by seeing yourself. It is something very honest about the piece and refreshing after centuries of painting royals!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.