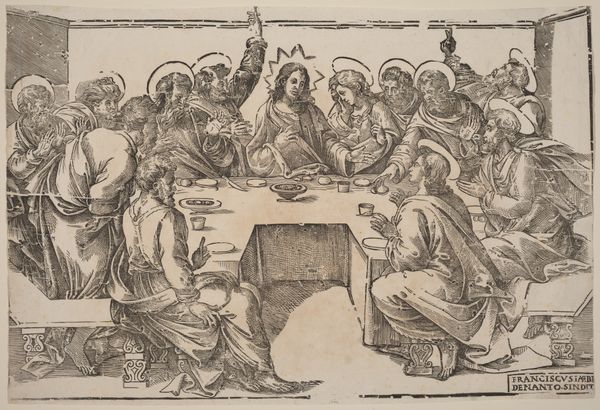

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

group-portraits

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 324 mm, width 382 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

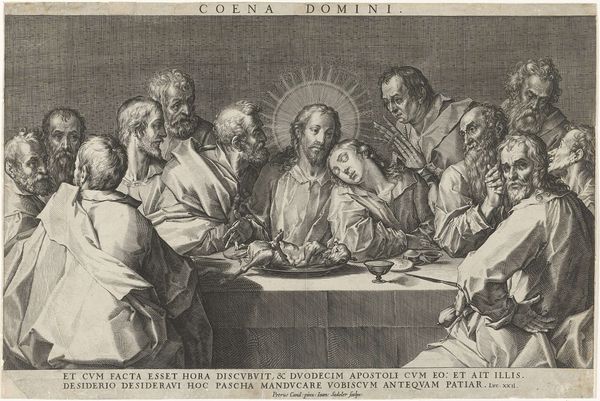

Editor: So, this is Johann Sadeler I's "Laatste Avondmaal," or "Last Supper," an engraving dating roughly from 1560 to 1650. It's got such a weighty feel to it, almost oppressive, with all those figures crammed together. How does this image speak to you? Curator: This print presents a powerful study of religious doctrine in a politically turbulent era. The "Last Supper" theme became less about pure faith and increasingly about demonstrating the power of the Catholic Church amidst the rise of Protestantism. Notice the theatrical lighting, the dynamic poses – hallmarks of Baroque art intended to inspire awe and reinforce authority. The print medium itself also speaks volumes. It made religious imagery accessible to a broader audience, functioning as a form of propaganda. Where do you see the political message within this engraving? Editor: Propaganda? Hmm, I was mostly focused on the somber mood and the detailed rendering. So, you’re saying that prints like this weren’t just devotional images but tools used in the conflict between Catholicism and Protestantism? Curator: Exactly. Think about who was commissioning and distributing these images. Powerful patrons, church leaders eager to sway public opinion and maintain control during a period of widespread religious questioning. Look closer at the expressions on the apostles' faces – some seem worried, others contemplative. It’s a deliberate effort to engage the viewer emotionally and intellectually. Editor: It's amazing how a simple print could be a battleground for such massive power struggles. I always looked at religious art on a purely devotional level. Now, the role of socio-political messaging changes everything. Curator: And that's the beauty of understanding art within its historical context. What started as a reflection of religious history is an open door to politics, society and control through visual narrative. Editor: That gives me a lot to consider about how imagery works within these timeframes. Curator: Precisely, always delve deeper. Art isn’t made in a vacuum, it's an echo of the times, a weapon of the powerful, and it influences how society interacts with politics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.