photography

#

portrait

#

self-portrait

#

pictorialism

#

portrait

#

photography

#

modernism

Dimensions: image: 8.7 x 11.5 cm (3 7/16 x 4 1/2 in.) sheet: 10.1 x 12.6 cm (4 x 4 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

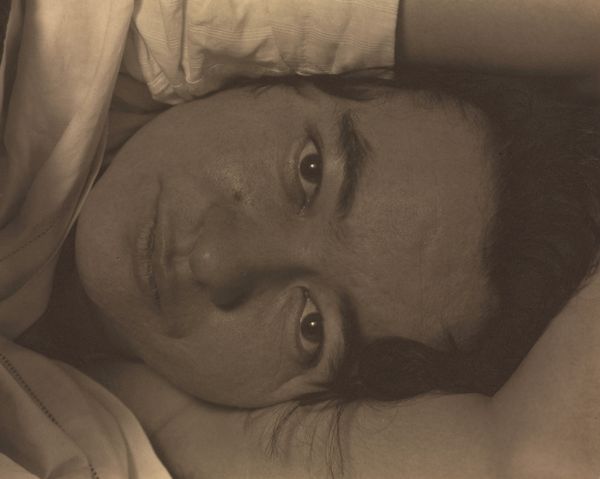

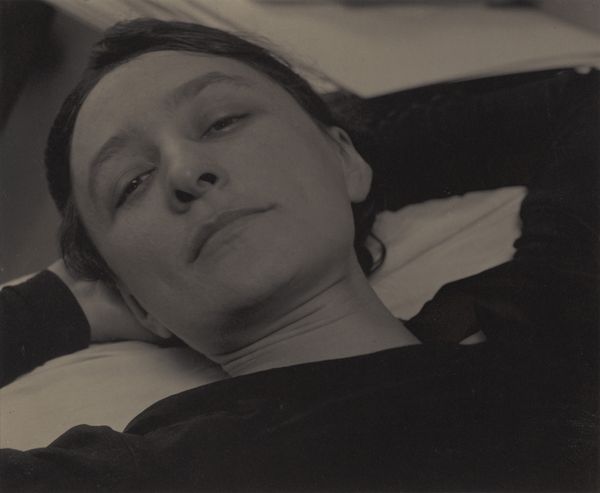

Curator: This is a photographic portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe, taken in 1918 by Alfred Stieglitz. It's an intimate image, capturing O'Keeffe during their early relationship. Editor: The first thing I notice is how vulnerable she appears. There's a rawness to her gaze. Almost as if we're intruding on a private moment. What can you tell us about the techniques used in this shot? Curator: Well, Stieglitz was a proponent of pictorialism and straight photography, emphasizing the photographer's control over the image-making process, from selecting the subject to printing. Here, we see soft focus which was very characteristic. The tones were often achieved using darkroom techniques to produce a print that resembles a painting, but without manipulation of the negative. The light is interesting in this work. What do you think? Editor: Right, the use of light creates stark contrasts, almost bisecting her face. It directs the viewer's gaze while also concealing, playing with the notions of revelation and privacy, which is crucial when understanding the narrative surrounding O'Keeffe as a woman artist negotiating patriarchal spaces. And, given their personal relationship, how does this dynamic influence the interpretation of this photograph as an art object? Curator: That’s key to my argument, I see how the soft-focus and grainy textures lend an almost tactile quality, drawing attention to the photographic process itself. He presented her in the readymade way. Stieglitz aimed to legitimize photography as high art, equal to painting and sculpture and here we can see it. This specific photograph helped solidify her image as a modern woman. Editor: Exactly. It raises critical questions about authorship, the male gaze, and the construction of female identity within the art world. And it’s this negotiation—between the artist, the photographer, and the viewer—that gives the portrait its enduring power. I still get a feeling that her gaze confronts established norms about femininity and representation. It feels brave. Curator: Yes, even a portrait is never neutral, is it? As much as we try, as objective art historians, there are things that resonate and are inevitably influenced by contemporary understandings. Thank you for making these points and questioning photography as art with me. Editor: Thank you. It reminds us how necessary it is to understand a work, and question the making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.