daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

romanticism

Copyright: Public Domain

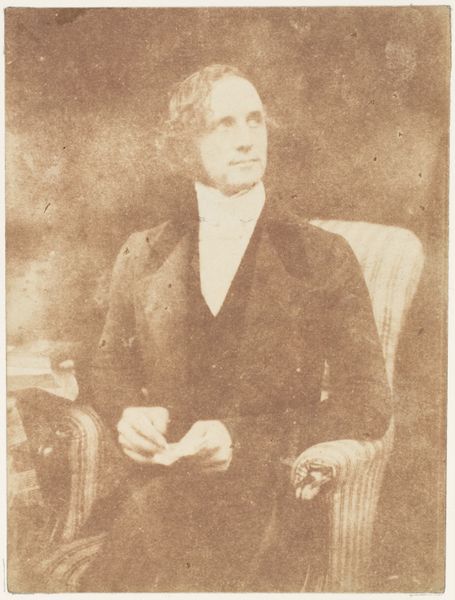

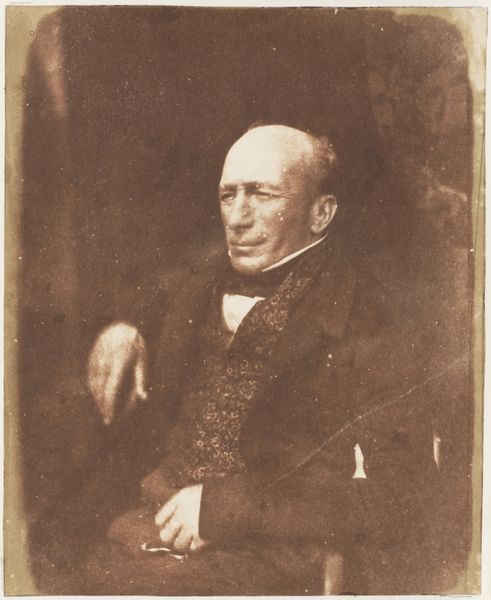

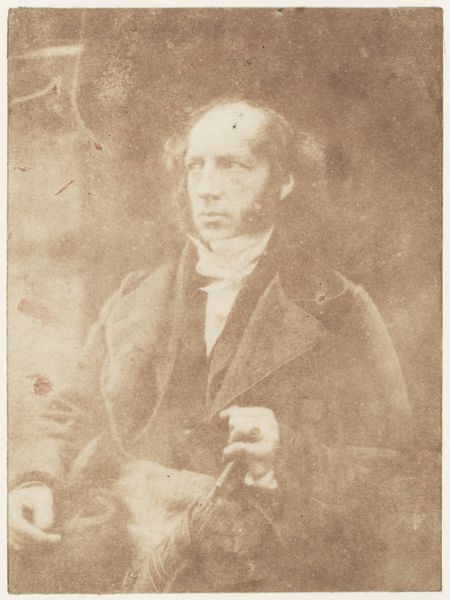

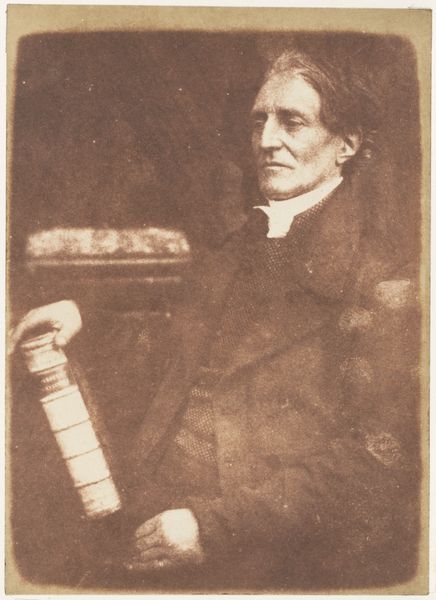

Editor: So, this daguerreotype, "Sir John Boilleau," by Hill and Adamson, made between 1843 and 1847. It's quite striking how the gentleman's pose and attire capture a sense of Victorian-era respectability, but I am curious, what do you see in this work beyond the surface of a formal portrait? Curator: What I see is an interesting interplay between the democratization of portraiture and the persistence of social hierarchies. Photography, even in its nascent daguerreotype form, offered a relatively accessible way to capture likeness, challenging the traditional dominance of painted portraits reserved for the elite. Editor: That’s a good point. How does this tension play out visually? Curator: Well, consider Boilleau’s attire and composed expression; he's clearly presenting himself according to established codes of conduct and class. Yet, the very fact that this image exists as a photograph speaks to the disruption of those same codes. The Romanticism tag hints at an idealization, but through a mechanical medium. Editor: I guess there's an irony there. The technology is new, but the social performance is very old. How did this portrait contribute to photographic traditions? Curator: Hill and Adamson were pioneers. Their use of photography extended beyond just portraiture; they documented everyday life. I find it a compelling exploration of representation at a pivotal moment, grappling with evolving notions of self and identity. It prompts us to consider photography's complicated relationship with truth and power. What do you think? Editor: It definitely challenges my initial impression. It's more than just a portrait, it's a document of shifting social dynamics! Curator: Exactly. Seeing photography within broader social and technological contexts helps us understand not only this one image, but how the medium has shaped our perception ever since.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.