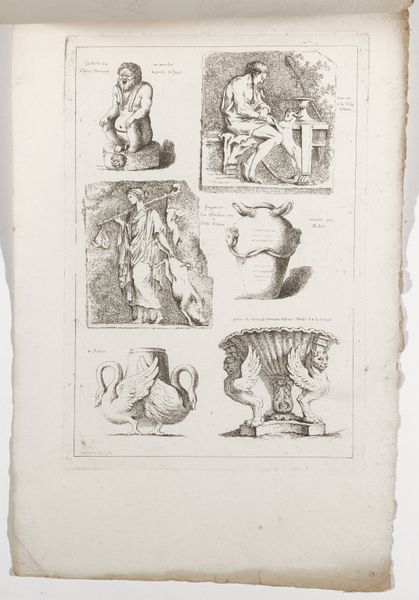

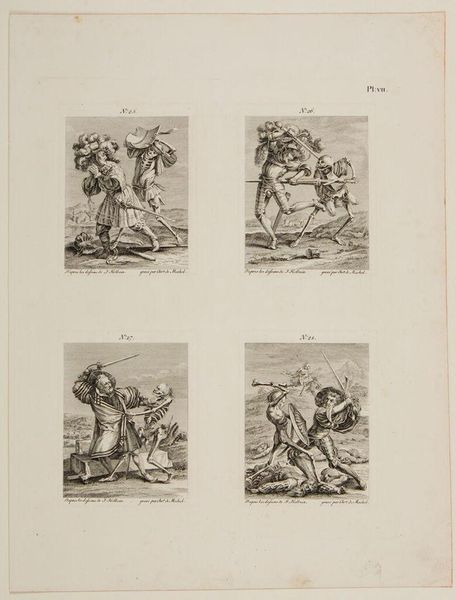

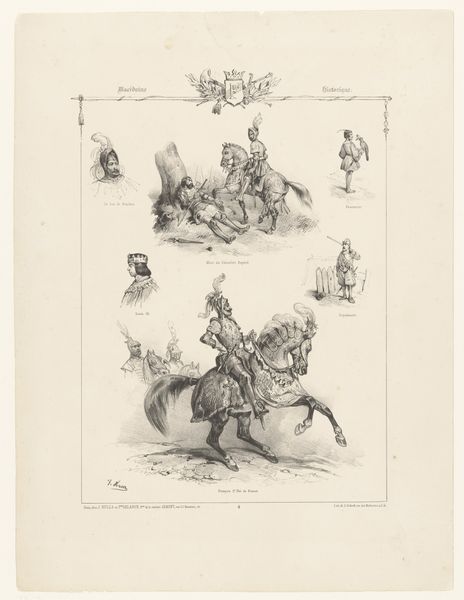

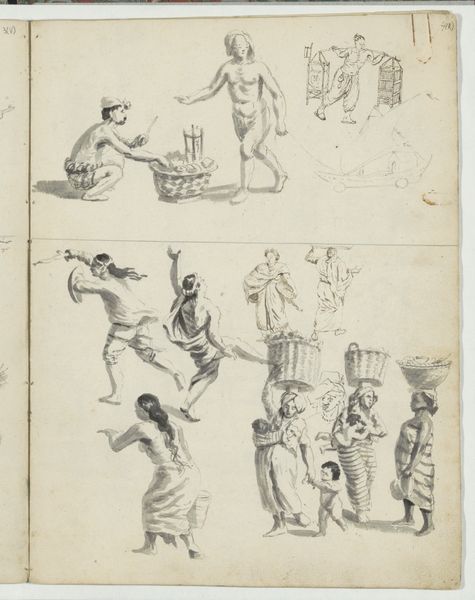

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 343 mm, width 228 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, made in 1728 by Bernard Picart, is entitled "Four Japanese Gods: Giwon, Jebis, Daikoku, and Tossitoku.” The engraving depicts…well, what’s your immediate reaction to this, Editor? Editor: It's striking! There’s a stiffness in the figures, almost a naive quality, yet something undeniably powerful emanates from each depiction, each in their respective tableau. Curator: Precisely. Consider the historical context. In the 18th century, Western perceptions of Japan were largely shaped by limited access and understanding. This print reflects European interpretations, perhaps filtered through a lens of Orientalism. We see what were believed to be four Japanese deities. Editor: I agree, the representation feels… mediated. Take Giwon, for instance, positioned atop a lotus, horned and emaciated; the stark lines accentuate a vulnerable figure. How do we interpret that fragility within the context of divinity, or perceived divinity, shaped by European ideas? Is it commentary or misrepresentation? Curator: That’s the crux of it, isn’t it? Picart draws from secondhand accounts. We have Jebis, supposedly a Neptune figure of the Japanese, clasping an enormous fish. Daikoku, shown here wielding a mallet and overseeing what appears to be a money bag, then Tossitoku, associated with fortune. How much is gleaned from the reality of Japanese culture, and how much is constructed by external views and agendas? Editor: The deliberate arrangement of the figures contributes. Separated into these starkly contrasting, boxed forms—they lack interrelation, flattened into almost allegorical stereotypes. In contrast, though, their attire, each rendered painstakingly, denotes attention to conveying their otherness accurately to a European audience. Curator: You can read these renditions, made in the baroque style, as allegorical reflections, shaped by colonial-era fascination. These were attempts to map unfamiliar beliefs onto European visual and intellectual frameworks. Editor: And how these images functioned politically and culturally in the reception of the art would be vital to understand fully the visual power of the pieces here. Curator: Definitely. What starts as seemingly straightforward engravings unfolds into layers of intercultural dynamics and assumptions. Editor: Precisely, looking closely, the composition allows us to acknowledge, more broadly, the colonial framework by which non-Western belief systems came to be recognized—or unrecognized.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.