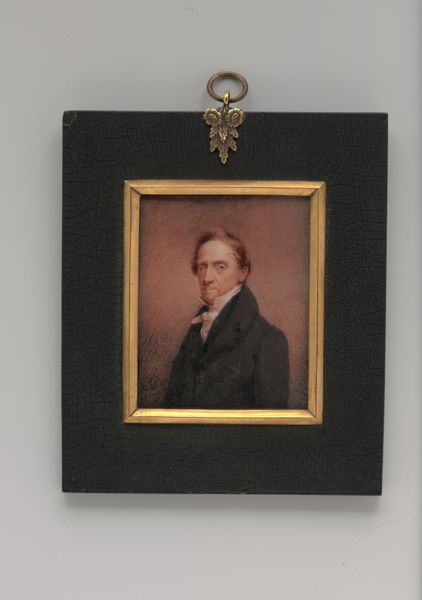

painting

#

portrait

#

painting

#

romanticism

#

men

#

portrait art

#

miniature

Dimensions: 2 1/4 x 1 11/16 in. (5.6 x 4.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have Thomas Seir Cummings' "Portrait of a Gentleman," dating from between 1840 and 1845. The materials are likely watercolor on ivory, presented in a gold frame. It's currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: What immediately strikes me is how delicate it seems, a palpable sense of intimacy. There’s a feeling of gentle melancholy, would you agree? It's so small and carefully rendered, a tiny window into another person's existence. Curator: Absolutely, and the context of portrait miniatures is important. They were intensely personal objects, often commissioned as mementos for loved ones, particularly for those separated by distance or even death. Their preciousness speaks to a very specific type of consumption within that time period. Editor: Yes, they functioned as deeply sentimental keepsakes within a social framework of strict class boundaries, mostly reserved for privileged elites. It evokes an awareness of absent presences and hidden connections across geographies. Curator: Indeed. The labor involved is substantial. Consider the time and skill needed to render such detail on such a tiny scale. This reflects a shift in labor practices—artist becomes artisan and the value resides as much in the process as the finished image. Editor: Right, and looking at it from an activist perspective, it's hard not to wonder about the identities unrepresented. Where are the portraits of the working classes or of people of color? Who controlled the narrative—and, by extension, visual representation—of that period? Curator: A valid point. Portraiture, especially at this scale and expense, often reinforced existing social hierarchies. It also gives you a lens into what society chose to deem important. Editor: The romanticism of the era permeates this miniature. A longing look... almost as if this man’s thoughts extend beyond the gilt frame. Curator: The craftsmanship serves its social function, too. These lockets became family heirlooms, a part of social class in history that continues to intrigue us. Editor: Thinking about what it meant for women of that period… these miniatures enabled portable remembrance, objects embodying an idealized image of husbands, fathers, and sons, and it allowed connection across a space and a longing to be expressed. Curator: So much more than a trinket; it is also about the artist's own social mobility through skill. Editor: Right, each brushstroke contributes to how the sitter wanted to be remembered in the grand theater of life, which we can only access via these surviving tokens. Curator: Thank you! Looking at these portraits offers so much beyond just what is there on the surface. Editor: Agreed. A tiny window with sweeping implications, indeed!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.