photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

wedding photograph

#

portrait image

#

wedding photography

#

harlem-renaissance

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

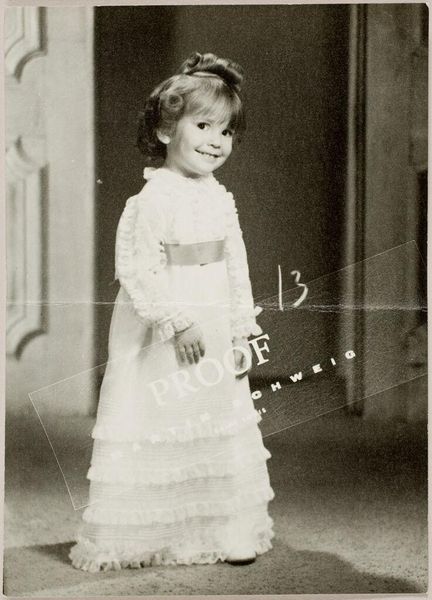

Dimensions: image: 17 × 11.8 cm (6 11/16 × 4 5/8 in.) sheet: 17.9 × 12.8 cm (7 1/16 × 5 1/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

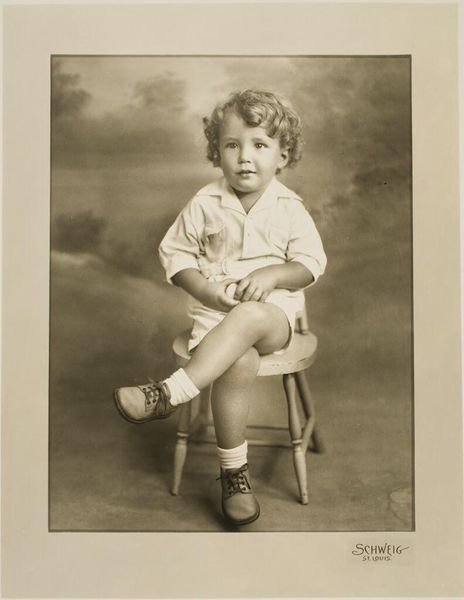

Editor: Here we have James Van Der Zee’s "Little John," a gelatin silver print from 1934. The subject's confidence is palpable! The way he's leaning, it almost seems collaborative. What draws your eye in this piece? Curator: My immediate reaction centers on the constructed reality within the image. The painted dog, the patterned linoleum, and the potted plant reveal much about Van Der Zee's studio and the aspirational setting being offered to his sitters. What was being sold here, alongside the photographic print, and to whom? What sort of labor was involved in assembling all of this, including constructing a compelling version of boyhood? Editor: So you're less focused on the boy and more on what the studio set suggests about the client’s desires, and maybe even the photographer's economic position? Curator: Precisely. We must also consider the wider societal and economic context in which Van Der Zee was operating. This was Harlem in 1934. What role did portraiture play within the community? Was the consumption of images such as this impacted by gender, class, or neighborhood reputation? How are the materials -- the silver and gelatin, the photographic paper -- indicative of wider trends in industry? These are the important questions to ask ourselves, not only, "what am I seeing," but how does this affect Black communities’ lives and economic opportunities at the time? Editor: I never really thought of a studio portrait having so many layers tied to economic status and material culture. It shifts the image from a simple representation of a child to a complex artifact! Thanks! Curator: Absolutely. Shifting the lens helps us look closer at who profited, both artistically and monetarily, from images and image production at that time, as well as at what cost.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.