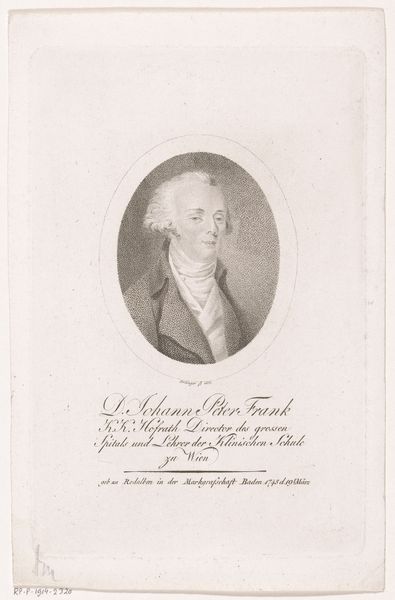

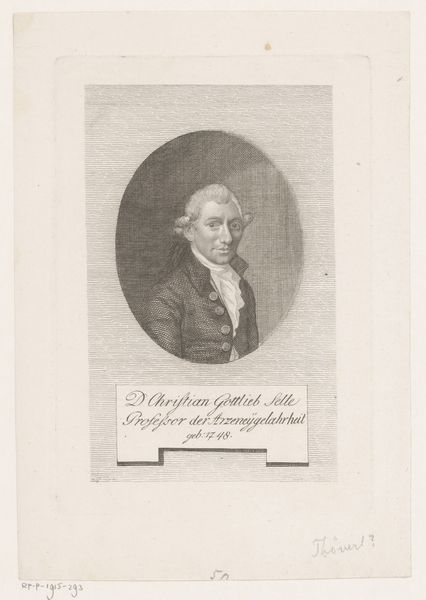

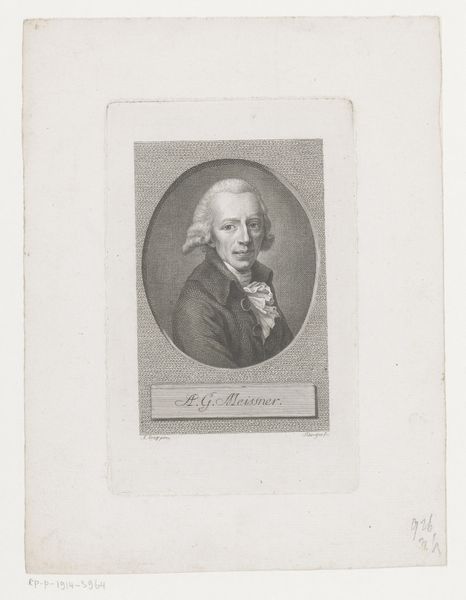

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 156 mm, width 98 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Portret van Johann Christoph Schwab," created in 1798. The artist, Friedrich Wilhelm Bollinger, masterfully employed engraving to capture Schwab's likeness. Editor: It's strikingly subtle, almost demure for a portrait. There’s a quiet confidence in the subject's gaze. I'm curious about what that slight smile conveys within the context of 18th-century portraiture. Curator: Schwab was a Hofreith, roughly translated, an advisor in the Duke of Wurttemberg's court, placing him within a very specific social and political stratum. This engraving, typical of Neoclassical portraiture, becomes a symbol of status. Notice the oval frame, meant to evoke classical cameos. How does understanding his social standing influence your reading? Editor: It amplifies that initial sense of quiet confidence. Knowing his position, the simplicity isn't humble; it’s a controlled presentation of power. The minimal ornamentation focuses all attention on his character, but still reinforces existing hierarchies and privilege. In what ways might we examine how the imagery of the court worked with and against the broader political tensions of the time? Curator: Bollinger, as the artist, played a role in cementing this visual language of power, contributing to a network of imagery circulating through aristocratic and intellectual circles. Consider the power dynamics implicit in the commissioning and creation of such a piece. Its dissemination and replication as a print is also meaningful to how identity was constructed and circulated. Editor: Absolutely, and the medium itself – an engraving – allows for reproduction and distribution. Was this primarily intended for a small circle, or did it have a broader intended audience, shaping how the role of the enlightened leader might circulate at the time? Curator: Given the context, I would suggest it was geared more toward a smaller, privileged sphere of influence and circulation. The engraving then solidifies this idea for future generations, who have limited ways to encounter the individual except through his carefully designed portraits, as historical records in institutions such as this museum. Editor: It's compelling to think about how artworks like this become, in a way, the gatekeepers of history. Seeing Schwab's image, filtered through the lens of both artist and patron, provokes consideration of who gets remembered, how, and on whose terms. Curator: Indeed. Through social and cultural art history, the piece expands beyond the aesthetics of the time and reflects something larger. Editor: And the focus on contemporary theory can examine whose stories might remain untold and hidden beneath dominant narratives of greatness and legacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.