drawing, print, photography

#

drawing

# print

#

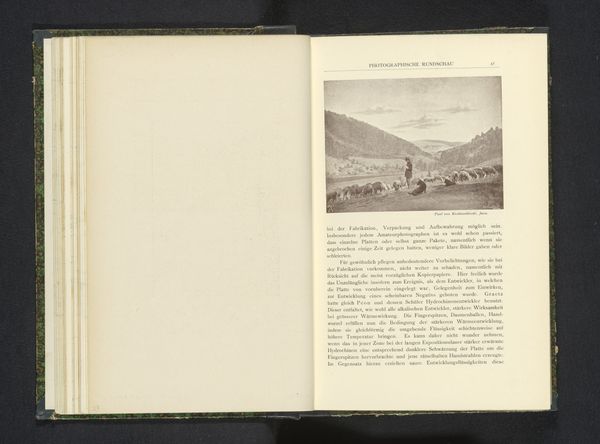

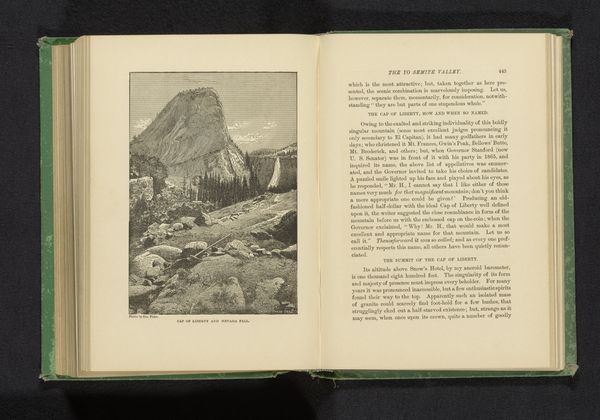

landscape

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: height 132 mm, width 99 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I find this photographic reproduction quite compelling. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It strikes me as rather melancholic. The muted tones, the almost ghostly figures of the deer… there’s a sense of quiet desperation hanging in the air. What can you tell me about it? Curator: This is a photo reproduction of a drawing entitled "Fotoreproductie van een tekening van jagers die sambars besluipen." It's attributed to Nicholas & Co., dating from before 1880. The scene appears to depict hunters stalking sambar deer, set within a rugged, mountainous landscape. I'm drawn to the narrative element captured. Editor: Yes, "stalking" seems apt. Considering it’s from before 1880, I’m interested in its historical context. The representation of hunting – a dominant colonial activity – brings forth critical questions around power dynamics, ecological impact, and cultural attitudes toward nature. It looks like the photographic elements are presented as if to record reality, to be a scientific observation. What does realism mean in a context of claiming land? Curator: That's a crucial perspective. Hunting narratives were, in effect, a projection of imperial authority. Through visual documentation of such activities, the colonizers justified their presence and domination, simultaneously establishing themselves as superior and exploiting the natural resources. Realism, in this context, serves as a powerful ideological tool. Editor: The image’s composition furthers that agenda. The looming stag with its antlers held high takes up nearly a quarter of the picture. Even if the picture shows that these stags are under threat, it romanticizes colonialist power at its expense. Curator: Absolutely. And if we analyze it using modern concepts like animal studies, we could expose a deep sense of environmental disregard. These images helped normalize practices of hunting which are inherently devastating. Editor: Seeing this through the lenses of feminism and ecocriticism is quite revealing. We cannot engage with its artistic qualities separate from what it politically performs. The landscape becomes an extension of that performance – a stage where power is asserted and dominance inscribed. The photograph therefore operates within a network of relations. It's about politics of space. Curator: Indeed, understanding these layered interpretations is crucial for our present moment, encouraging us to look at history not just through an aesthetic gaze but also through critical perspectives. Editor: Agreed. I initially only saw melancholia but I am moved now by how the image asks us to question embedded hegemonies. It serves as a potent artifact when re-contextualized to explore critical conversations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.