De met bloed bevlekte mantel van Jozef aan Jacob getoond 18th century

0:00

0:00

giovannivolpato

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, paper, watercolor, pen, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

pen

#

watercolour illustration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 525 mm, width 775 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

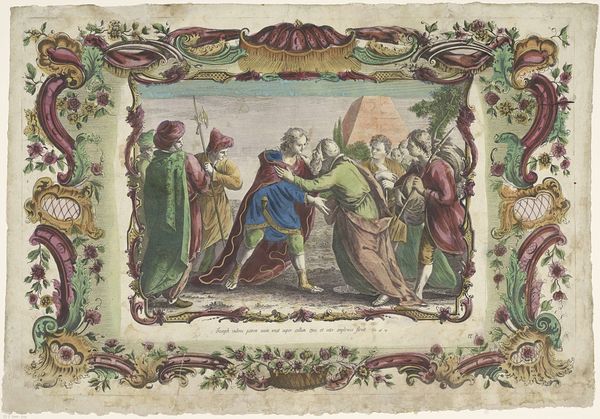

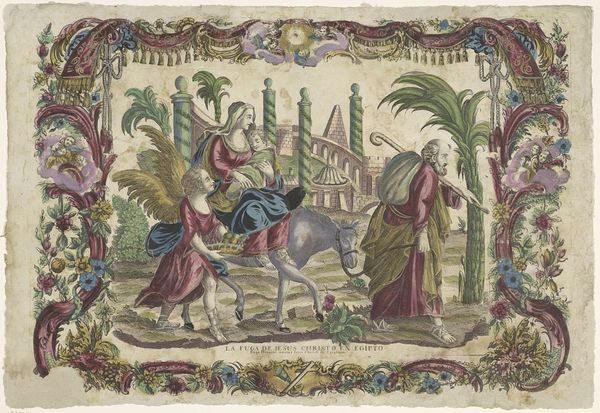

Curator: This is an 18th-century print, currently held at the Rijksmuseum, titled "De met bloed bevlekte mantel van Jozef aan Jacob getoond," or, "Joseph's bloody coat shown to Jacob," made with pen, watercolor, and engraving by Giovanni Volpato. It portrays a moment of intense emotional distress. What are your immediate thoughts? Editor: Visually, the composition strikes me as theatrical. The figures are arranged almost like actors on a stage, emphasizing the drama of the scene. There is something unsettlingly artificial about the decorative border, too, in relation to the tragic biblical scene that it depicts. Curator: It is a potent scene isn't it? Volpato captured a pivotal moment from the Book of Genesis, the sons presenting Joseph’s bloodied coat to their father Jacob, leading him to believe Joseph has been killed by a wild animal. Representations like these gained popularity during a time when visual narratives played a significant role in shaping social and moral consciousness. Editor: Absolutely. Consider how the presentation itself – the display of the bloody garment – becomes a form of cruel spectacle and manipulation. How might this resonate with contemporary issues of evidence, truth, and manufactured consent? The artifice in the surrounding rococo elements serves almost as a comment, underlining a sort of courtly and decadent lack of true, empathetic engagement with profound grief. Curator: You're right, that Rococo border almost softens the harshness of the scene for an aristocratic sensibility. The bloody coat as 'evidence' is powerful; note how Volpato uses the dramatic lighting to direct our gaze toward the grief-stricken Jacob. These depictions often functioned to reinforce social hierarchies and gender roles, with emotional displays expected of men, in particular. Editor: Indeed, we can unpack the loaded ideas about grief, masculinity, and power intertwined here. How are those representations historically contingent? This depiction almost certainly was seen very differently two or three centuries ago. In my mind, this image challenges us to analyze how patriarchal structures use displays of emotion, especially male pain, as mechanisms of control. Curator: I agree. And within that 18th-century framework, prints like this also played a role in the burgeoning art market, accessible to a broader audience than paintings, thus shaping cultural sensibilities and religious understanding among various social strata. The print’s very accessibility contributes to a democratizing of the narratives, whilst the style somewhat undermines any depth of genuine pathos. Editor: Thank you for highlighting that point; it encourages reflection about how media technologies can both empower and manipulate perception and meaning. Examining prints like these permits us to appreciate how representation informs social identity even today. Curator: Precisely. Seeing those historic roots definitely casts contemporary culture into sharper relief. Editor: A vital recognition. Let us turn to the next exhibit, shall we?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.