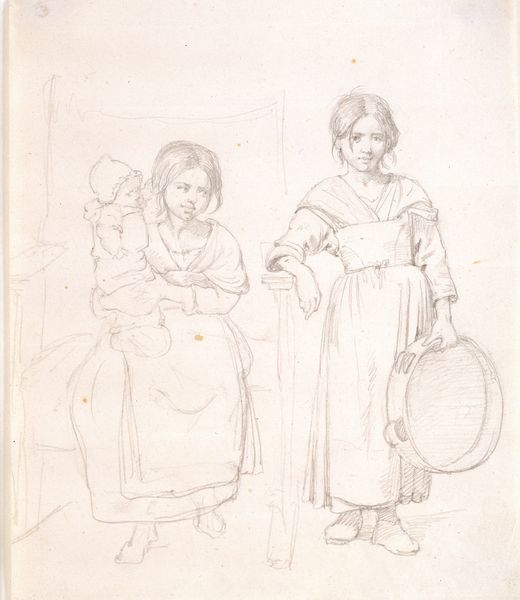

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: 261 mm (height) x 260 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Looking at this delicate pencil drawing, "To italienske piger, den ene med et barn på armen," by Martinus Rørbye from 1836, one immediately appreciates its quiet simplicity. Editor: Yes, quiet indeed. There's an undeniable sense of the everyday struggles faced by women in 19th-century Italy imbued in the almost washed-out aesthetic. I feel it viscerally, the hard labor softened by the gentle hand of motherhood. Curator: Absolutely. The way Rørbye captures the texture of their garments and the simple rendering of their bare feet suggests a particular socio-economic context, speaking volumes about the lives of ordinary women in that era. I am interested in his specific material choices. Did the available paper contribute to the limited tonal range we see here? How does his drawing style articulate his vision as well? Editor: That vision, from a gendered perspective, shows an insightful appreciation for the resilience of these women. Think of the history these figures embody – they’re not idealized beauties. They're working-class women carrying the weight of domesticity and societal expectations. The softness of the drawing adds, perhaps paradoxically, to their quiet strength. How might these scenes play within the wider narrative of women's representation in art, especially at a time where romanticism met burgeoning social critique? Curator: I agree entirely. It’s fascinating how Rørbye navigates that line, blending Romantic-era fascination with the foreign, exotic "other" with the raw, visible realities of labor and life for these Italian women. He isn’t depicting the grand landscapes but zeroing in on human realities and interactions. I suspect that his reliance on sketching—drawing, especially—may have contributed to his success with the approach of showing reality rather than simply representing it. Editor: Exactly. It almost feels as if Rørbye aims to convey that labor is part of everyday life, making visible an unspoken dimension that the grand narratives so often bury, right? The gaze, the materials and form contribute to conveying what could be called “dignified hardship." He highlights these individual experiences without stripping away their humanity—a potent mix of art, documentation, and implicit activism. Curator: I am fascinated, truly, by the intersection here, where we meet at these crossroads of art, history, and society. Thanks so much! Editor: And likewise—this piece, in its unadorned simplicity, creates dialogues and calls to revisit unexamined narratives!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.