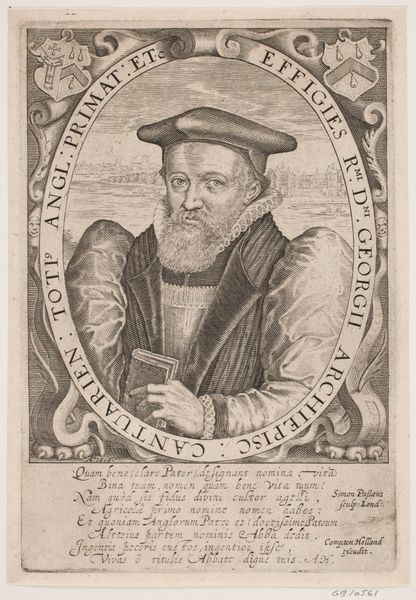

graphic-art, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

graphic-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

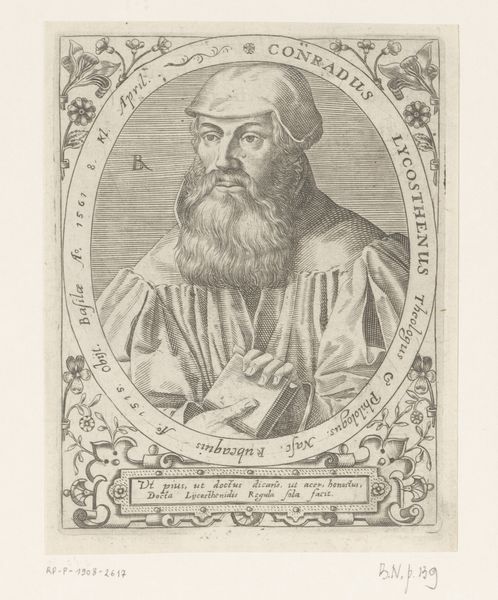

Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 107 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look closely at this engraving, a portrait of George Abbot. It was likely created sometime between 1597 and 1669, and is currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. The artist was Theodor de Bry. Editor: My initial reaction? Austere. Very detailed. You can see the texture in the clothes but it’s primarily the face—the lines etched to create that solemn expression—that draws you in. The engraver's skill is striking. Curator: Absolutely. This print served a very specific social function. Portraits like these were vital for disseminating the image of powerful figures like Abbot. It’s about projecting authority and respectability in a period where print was increasingly accessible. Editor: So, propaganda in a way? It's fascinating how the technique reinforces that. The very process of engraving – the physical labor of cutting into a plate – it speaks to a deliberate, almost immutable quality. This wasn't a quick sketch; this was an investment. I’m really noticing how the patterns almost overwhelm the figure, from the ruff around his neck to that busy oval frame, contrasting against the simplicity of his face and steady gaze. Curator: Indeed, there's a lot to unpack. Abbot was a significant Archbishop of Canterbury during a tumultuous period in English history, the Jacobean era, when religious and political tensions were extremely high. The Latin inscription suggests an educated audience, further reinforcing Abbot’s stature within intellectual and ecclesiastical circles. Editor: I wonder, who would have commissioned this and for what purpose? I suppose access would have been somewhat democratized, especially since paper was common as a cheaper ground than canvas. The materials imply that prints such as these were perhaps made to circulate broadly. Curator: A complex set of relations shaped works such as this. Commissioners, printmakers, distributors, buyers—all operating within the political and religious tensions of the period. This image acted as both record and public statement. Editor: Thinking about the craft of it all, the tangible reality of transferring ink onto paper… it changes my perspective. It brings the past closer. Curator: Precisely, it allows us to engage with history in a tangible way. These artifacts connect us to a world of power, belief and skillful making that feels very different, and yet strikingly familiar.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.