photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

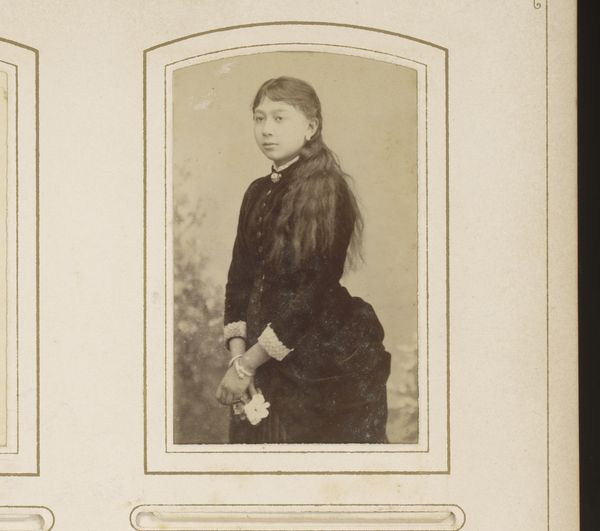

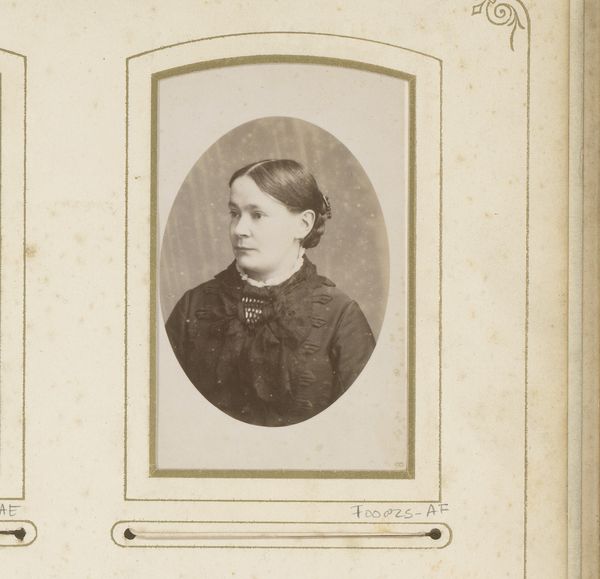

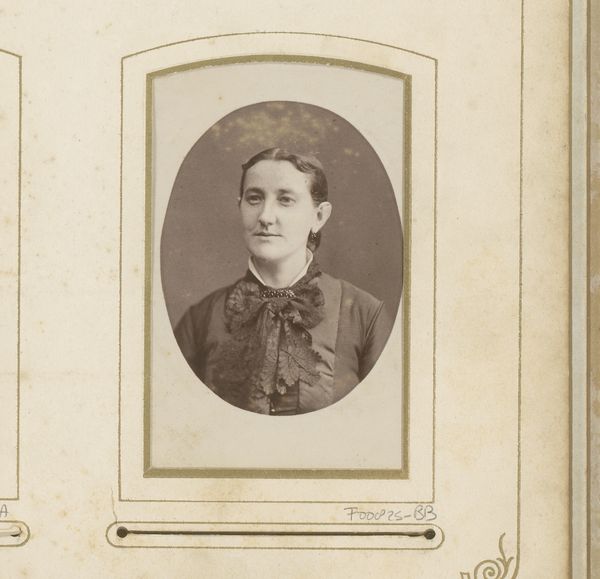

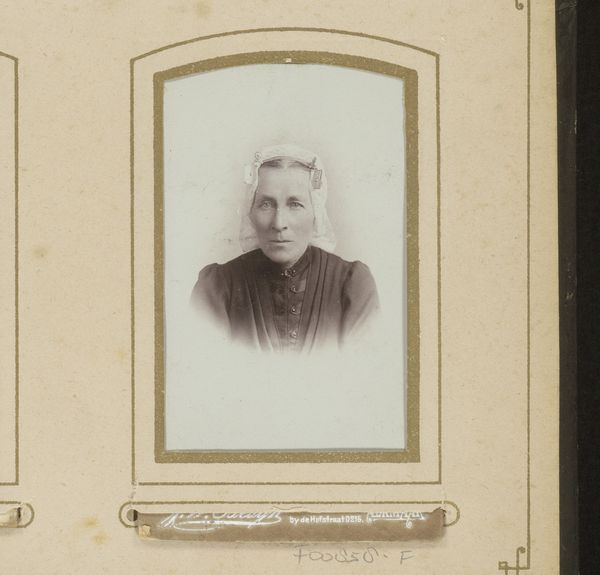

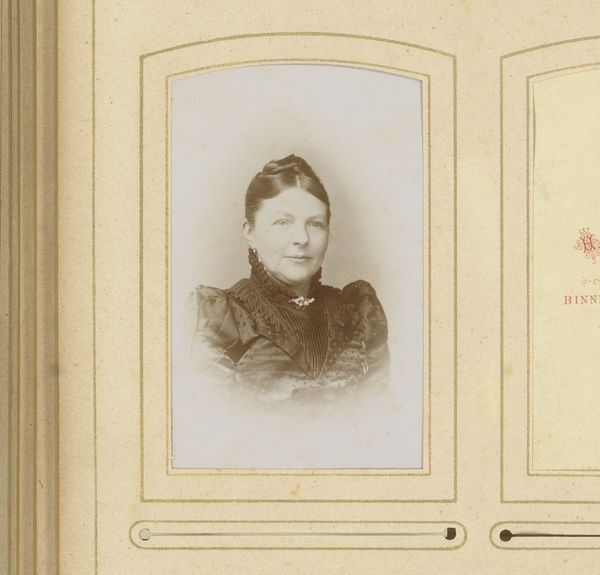

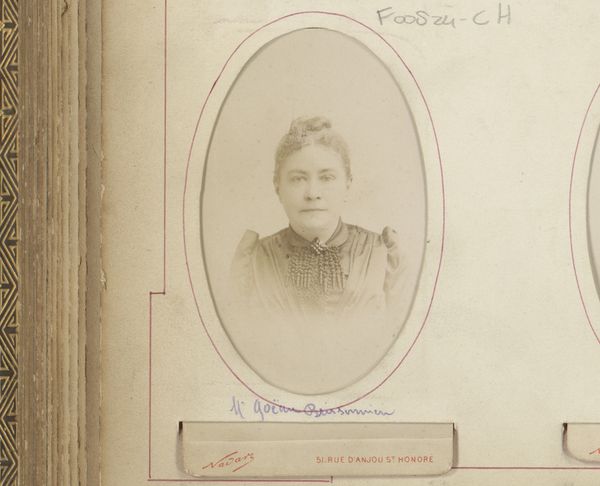

Curator: Welcome. Before us we have “Portret van een vrouw” – Portrait of a Woman – a gelatin-silver print captured by H.W. Schrier sometime between 1899 and 1903. Editor: She’s rather lovely, isn't she? It has an understated grace. You know, those old photographs feel so loaded, like silent time capsules whispering secrets. There's something quite haunting about them. Curator: Precisely! The formal composition, encapsulated in that perfect oval frame, enhances her contemplative mood. Note how the monochromatic tones and sharp focus pull us directly into her gaze. Editor: It's the contrast, I think. The soft glow of her skin against the dark fabric of her dress... very striking. She looks composed but not untouchable; approachable. Like you could share a secret. Do you think this image flattens her, or does it amplify her being? Curator: That is an interesting question, since flattening is intrinsic to the photograph itself! However, what is intriguing to consider is the photograph's referentiality—her dress, hair, all signs which create meaning by which we place her socially. Her image gains meaning as an exercise of codes, a product of a very specific cultural construction. Editor: And she actively participated in that construction, didn’t she? Choosing the dress, agreeing on her pose… it makes you wonder, doesn't it? What was she trying to communicate? And to whom? Curator: The direct address establishes a powerful dyad between the viewer and the subject. Consider the inherent paradox – the portrait aims to immortalize, yet it captures only a fleeting moment, a construction of self through which our understanding is always refracted. Editor: The beauty of realism is, despite that fragmentation, in the feeling it creates; its ability to distill real emotion from such rigid forms, creating, sometimes, an intimacy over a distance of a century. Curator: Yes, it’s true that, even a century removed, a powerful work still manages to retain its ability to intrigue and evoke response. Editor: Ultimately, that is what good art is. Making us see, making us feel... it does not always require grand statements; it can live, as in the case of this beautiful, anonymous portrait, in quiet contemplation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.