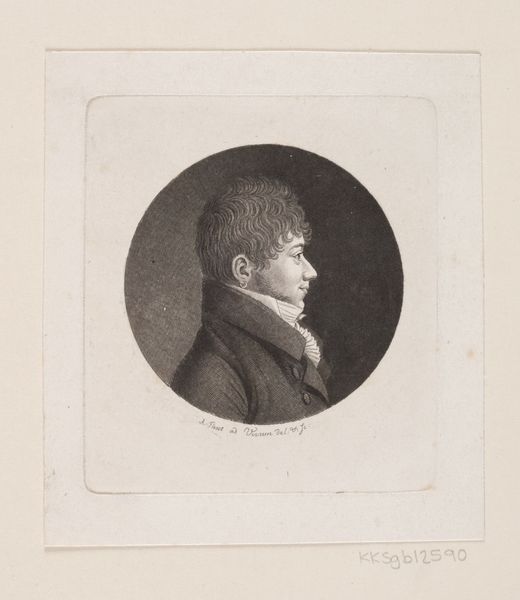

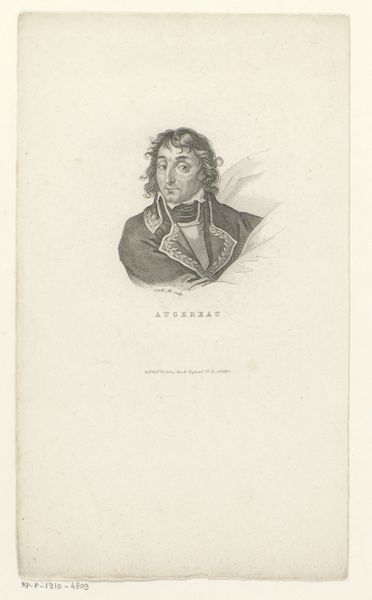

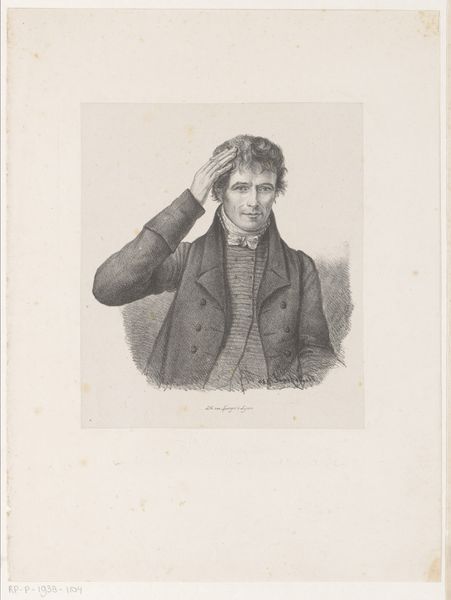

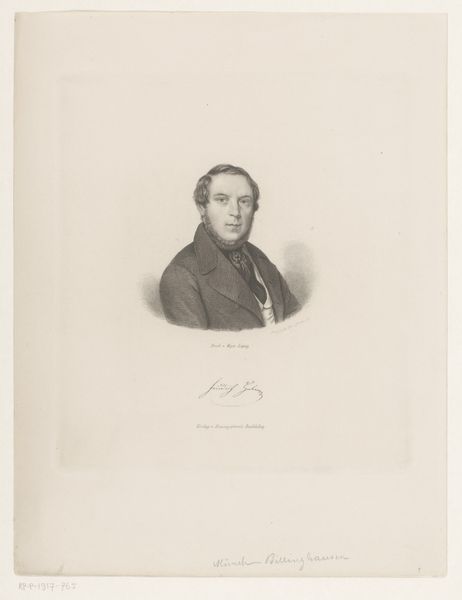

lithograph, print, paper, ink

#

neoclacissism

#

lithograph

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

paper

#

ink

#

history-painting

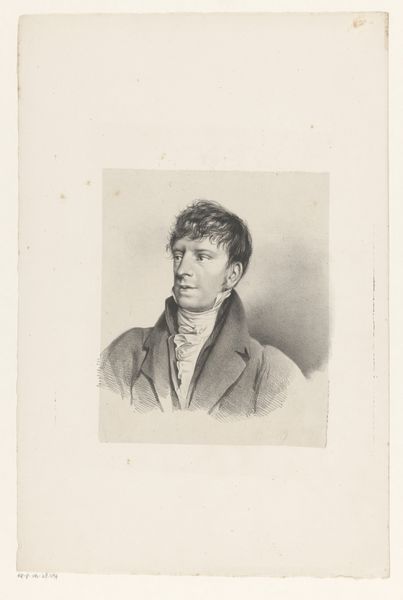

Dimensions: 362 mm (height) x 274 mm (width) (bladmaal), 123 mm (height) x 128 mm (width) (billedmaal)

Editor: Here we have a lithograph from somewhere between 1786 and 1824, entitled "Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein Stub". The piece appears to be printed on paper, presumably using ink. I'm really struck by the clean lines and how the artist used shadow and light in such a refined way. What do you see in this piece beyond its surface appearance? Curator: Beyond the Neoclassical aesthetics evident in the portrait style, I find it compelling to consider the work within the context of its historical moment. This portrait immortalizes Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein Stub, yet its creation also perpetuates a visual language that, even then, was heavily invested in maintaining power structures. Editor: That's a powerful thought. Are you referring to the conventions of portraiture used in Neoclassicism? Curator: Precisely. Note the idealized features, the slightly elevated gaze, and the subtle yet deliberate indications of status. Neoclassical portraiture, with its roots in antiquity, inherently communicated notions of authority and social standing. But considering the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as revolutionary ideas circulated, how might the presentation of Kratzenstein Stub reinforce or perhaps even subtly contest those societal hierarchies? Editor: I guess the simple fact that it's a print means it could have been distributed fairly widely. So, perhaps it's nodding towards existing power structures but is, in some ways, accessible in a new, more democratic way? Curator: Exactly! And what does the inclusion of that willow tree beneath the portrait suggest to you? Can it act as a symbol in this context? Editor: Hmm… Well, willows can symbolize mourning, but also resilience and flexibility… So maybe it represents a subtle awareness of the shifts happening at the time? I definitely didn't notice any of that at first glance. Thanks! Curator: It's in considering these layered readings that art history really comes alive, prompting us to question not only the intentions of the artist but also our own position as viewers, separated by centuries of social change.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.