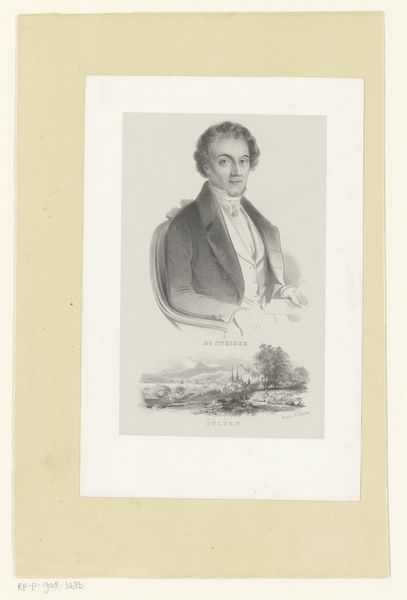

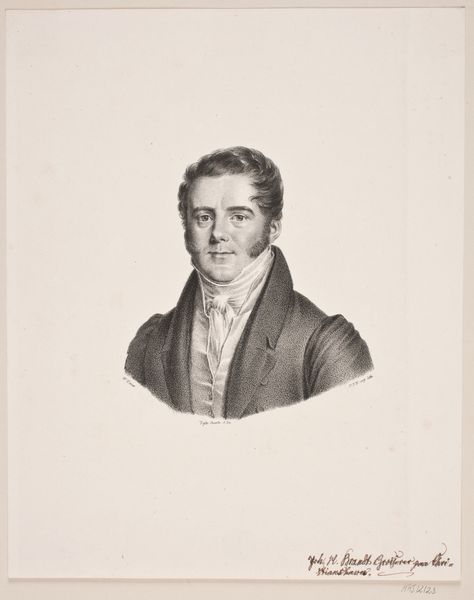

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

miniature

#

realism

Dimensions: height 244 mm, width 174 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have an engraving titled "Portret van W. Baarslag," dating somewhere between 1834 and 1866, by Willem Grebner. The figure looks so serious, and the detail in the coat is striking. How would you interpret this work? Curator: This print offers a glimpse into the democratization of portraiture during the 19th century. Engravings like these allowed for wider circulation of imagery and were crucial in shaping public perceptions of individuals, even outside elite circles. This isn’t just about W. Baarslag as an individual; it's about how print culture facilitated the rise of a broader visual public sphere. Editor: So, the act of making a print changes how we see this person? Curator: Precisely. Before photography became ubiquitous, prints served as a primary means of disseminating images. Academic art valued realistic representations. Consider how the very act of creating and distributing such an image conferred a certain level of importance on the sitter, influencing their public image and potentially shaping narratives around them. Who *was* considered worthy of depiction, and *why*? Editor: I see. It’s less about the individual’s accomplishments and more about the cultural context of image-making. Curator: Exactly! The miniature and history-painting themes reflected social aspirations, yet print as a medium complicates our understanding because of how far images could travel from the elites. What is the significance, in your mind, of depicting people outside the traditional realm of power within artistic spaces? Editor: It reveals evolving social structures! I hadn’t thought about how print democratizes visibility. Curator: And it raises fascinating questions about who gets remembered and how their image contributes to a collective historical memory. Considering how this was made for potentially wider dissemination really changes its impact.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.