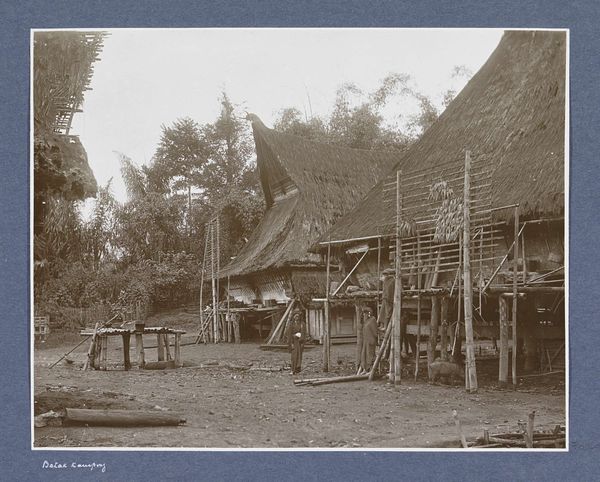

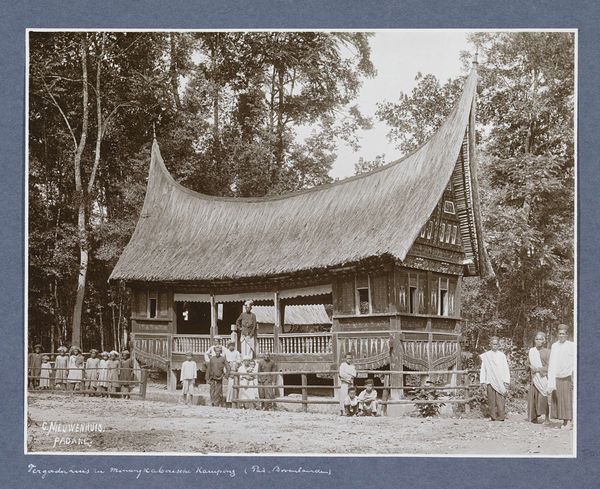

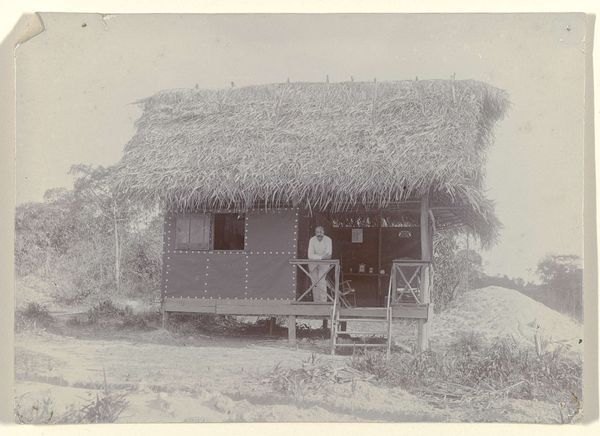

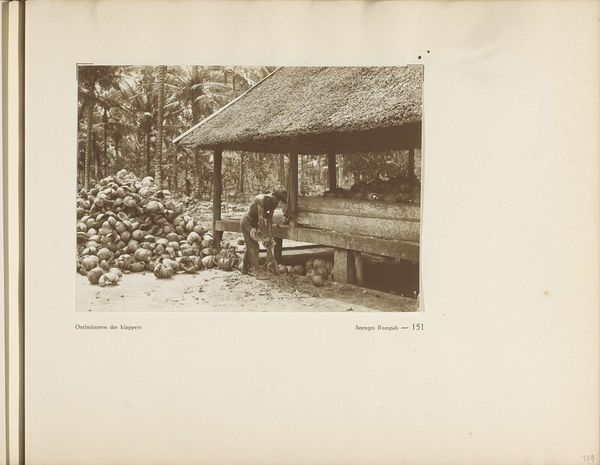

Batakse vrouwen en kinderen poserend voor een huis op Sumatra c. 1900 - 1920

0:00

0:00

christiaanbenjaminnieuwenhuis

Rijksmuseum

photography, site-specific, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

landscape

#

indigenism

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

site-specific

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 169 mm, width 229 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a fascinating tableau. We’re looking at a gelatin silver print titled "Batakse vrouwen en kinderen poserend voor een huis op Sumatra," which translates to "Batak women and children posing in front of a house in Sumatra." It's believed to have been captured sometime between 1900 and 1920 by Christiaan Benjamin Nieuwenhuis and currently resides at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The immediate feeling is one of quiet dignity. There's a stillness, almost posed theatricality, in the way the figures interact with this rather grand dwelling. It’s hard not to read it as an attempt to capture a particular moment in their history and cultural identity. Curator: It's true. Nieuwenhuis, through the lens of his camera, freezes a moment ripe with cultural symbolism. The house itself speaks volumes. Notice the elaborate decorations, the elevated structure – these architectural elements are deeply embedded with cosmological and social significance for the Batak people. What sort of reading can you extract from this architectural “memory?” Editor: Absolutely. The figures too contribute immensely to the story. The women’s positioning, the children’s gaze – there's an interplay between their individual presences and their collective representation of Batak culture at that time. It raises questions about representation, visibility, and whose narrative is truly being documented here, though. Given it’s a colonizer-era photograph, I cannot avoid these socio-political lenses. Curator: A valid critique. The very act of photographing indigenous communities was fraught with power dynamics. Yet, within that problematic framework, we can still discern elements of self-representation, or at least a negotiation of identity. The architectural image provides, indeed, a sense of self-determination. Editor: Perhaps the ornamentation is a sign of resilience? As a historian, I'm drawn to thinking about this image within the broader context of Dutch colonial influence, how power was projected through images and how local populations found agency within this. It’s a powerful reminder of the complexities inherent in the history of photography itself. Curator: Yes, it acts as a point of contact that reminds the viewer that photography as memory storage becomes part of a much wider discussion surrounding historical narration, ethnic representation and cultural psychology. It has certainly ignited a vibrant exchange about this captivating work. Editor: Indeed, and hopefully spurred some reflection on the multifaceted history held within a single frame.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.