painting, fresco, enamel

#

allegory

#

painting

#

sculpture

#

mannerism

#

fresco

#

enamel

#

decorative-art

#

miniature

Dimensions: overall: 7.6 x 9.3 cm (3 x 3 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

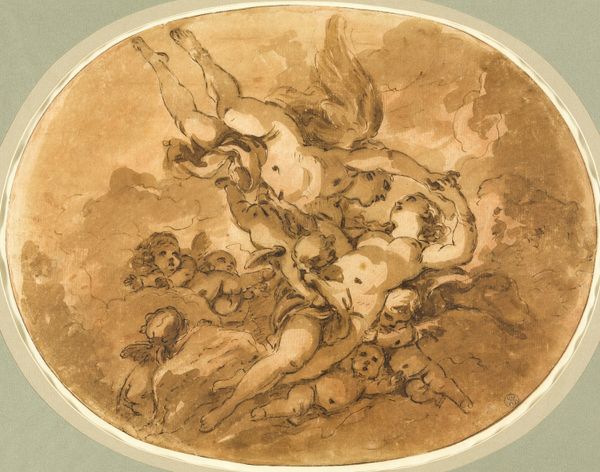

Curator: The piece before us, crafted by Pierre Reymond around the mid-16th century, is entitled "Plaque with Ganymede." It's an enamel painting, demonstrating Reymond’s mastery of the medium. Editor: It’s so striking, isn't it? There's this ethereal quality to it, a certain dreaminess underscored by the stark contrast between the deep black sky and the almost luminescent figures. Curator: The use of enamel allows for that stunning level of detail, wouldn't you agree? But beyond technique, the subject matter is key. We see Ganymede, a mortal youth, being abducted by Zeus in the form of an eagle. Editor: And that abduction itself is laden with historical and cultural implications. It speaks to the power dynamics of the time, not only divine over mortal, but the homoerotic undercurrent, given Zeus's intentions towards Ganymede. It's difficult to ignore the potential violence inherent in the scene too, wrapped up as it is in this beautified, almost romantic package. Curator: The visual vocabulary certainly draws from established traditions. Zeus's eagle form is immediately recognizable. In the allegory, Zeus rewards Ganymede’s beauty with immortality, transforming Ganymede to become his cupbearer. That symbolic role carries immense weight. It presents power, desire, and transformation interwoven through imagery deeply embedded in Greek mythology and its Renaissance reception. Editor: Precisely, it’s how these classical narratives are reshaped, re-presented, often sanitized, and used to either challenge or reinforce prevailing ideologies. Who is Ganymede in this narrative, what did he represent for different viewers in different eras, and how did the homoerotic context evolve over time? Curator: It all speaks to the incredible persistence of certain narratives and their evolving symbolic meaning over time, something the Renaissance artists were keen on highlighting, while adapting, rejecting, or subtly critiquing their sources. Editor: Definitely. It makes me think about whose stories we elevate, who gets to be immortalized in art, and how the art we create inevitably perpetuates particular biases and perspectives. It’s more than a beautiful tableau; it's an exercise in power, myth, and the negotiation of identities. Curator: Indeed. Gazing upon this plaque, we witness how an apparently straightforward scene acts as a mirror reflecting centuries of changing social, aesthetic and, quite possibly, even moral values. Editor: For sure. It's not just about what the artist depicted but the continuing conversations it enables, even centuries later.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.