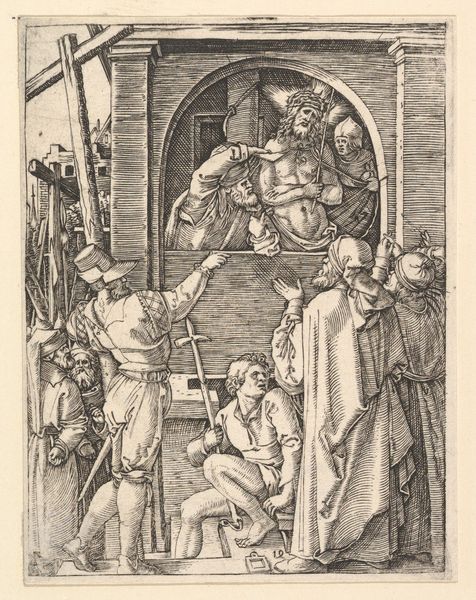

Engel drijft geblinddoekt kind met zweep voor zich uit in tredmolen 1590 - 1624

0:00

0:00

boetiusadamszbolswert

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 96 mm, width 57 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I’m immediately struck by the stark contrast between light and shadow in this engraving; it feels incredibly bleak and claustrophobic. Editor: We’re looking at “Engel drijft geblinddoekt kind met zweep voor zich uit in tredmolen,” made by Boëtius Adamsz. Bolswert sometime between 1590 and 1624. It resides in the Rijksmuseum’s collection. What’s particularly interesting to me is the use of engraving, a meticulous process of carving into a metal plate, which inherently links the final image to a specific mode of labor. Curator: Precisely! The repetitive action in the image echoes the labor-intensive technique. You've got a blindfolded child relentlessly walking, driven by an angel’s whip, powering what appears to be a grain mill. The treadmill construction and implied mechanism of operation become focal points. Editor: Absolutely, and consider the social context. We’re seeing this image circulated as a print; it’s relatively accessible compared to painting. Bolswert's choice of subject, this almost allegorical scene of forced labor, resonates with contemporary issues of social injustice. Is this artwork trying to offer us any social commentary through the politics of its imagery? Curator: That’s certainly one reading. We could also think about the distribution network. How did these prints circulate? Were they commenting on child labour in the production of goods, were they propaganda for charitable causes that sort to relieve impoverished communities or religious commentaries on work? Who consumed them, and what kind of conversations did they provoke in the places they were circulated? Editor: It makes you consider who benefitted from what may have been illustrated by this artwork. Was the artist involved in those industries, was this their personal take on such activity? Curator: All this attention to how prints were made, disseminated and put into service encourages one to think critically about the materiality of imagery in the early modern world. Editor: It's a compelling piece for understanding the social underpinnings of early modern printmaking, offering insights into labor, material production, and image circulation. Curator: It offers much for contemplation about labour, religion and children's working conditions in 17th-century workshops.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.