#

comic strip sketch

#

light pencil work

#

quirky sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

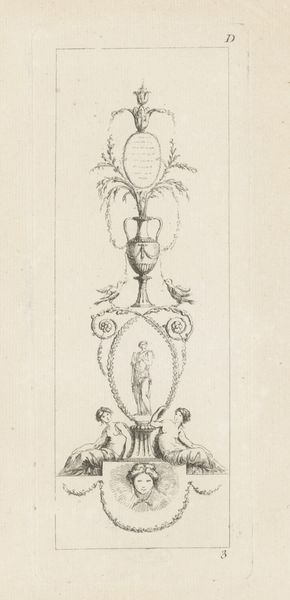

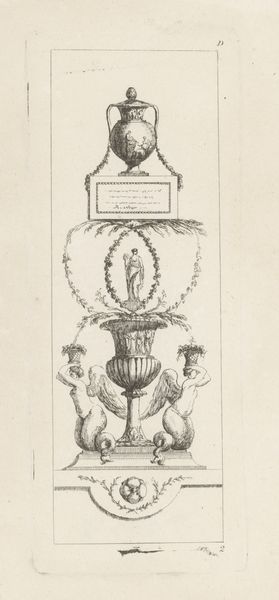

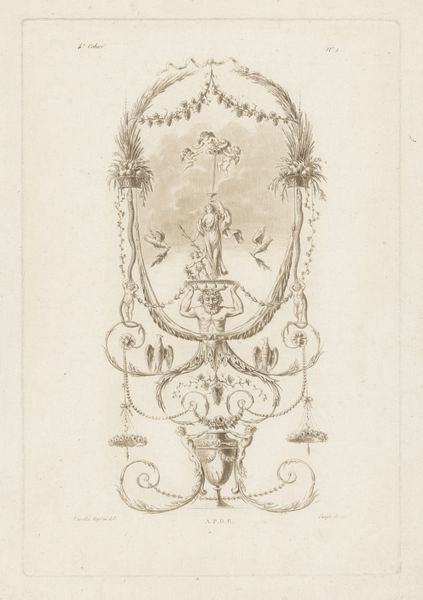

Dimensions: height 209 mm, width 79 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

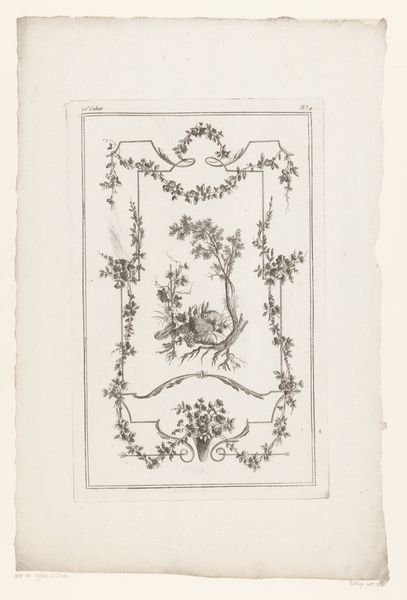

Curator: This drawing, titled "Vaas en medaillons", roughly translating to "Vase and Medallions," dates from between 1752 and 1782. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. The artist is identified as Juste Nathan Boucher. Editor: My immediate reaction is a sense of whimsical, almost playful elegance. It feels light, airy. Like something you'd see adorning the stationery of a fashionable 18th-century lady. Curator: I agree, there’s definitely a lightness to it. Consider Boucher’s position at the intersection of Rococo's fading influence and the rise of Neoclassicism. How do you think those shifting social tastes might impact his rendering of vases and mythological figures? Is this about the feminization of interior design through seemingly innocuous things such as a pretty vase? Editor: I see that tension reflected beautifully in the imagery. The vase, an ancient symbol of bounty and containment, grounds the piece. It is placed at the bottom and top of this series, bookending other classical symbols. Look at the feminine figure in the medallion. Does that suggest virtue, piety, or some other classical ideal? Curator: Possibly both; and yet consider who such virtues often benefited. Might Boucher be subtly interrogating how idealized womanhood was deployed to serve power structures? Who can ascend and benefit from the classical and neoclassical styles. Editor: I love how this connects. And, of course, vases themselves, historically, have been repositories not just of flowers, but of cultural narratives. Aren't vases often a domestic representation of feminine status or role? What are the materials used, the type of flower displayed, its purpose in the household... This feels more complicated when the vase is paired with other medallions containing portraits and allegorical figures in one object. Curator: Exactly. And Boucher, working in this transitional period, is seemingly conscious of these shifts, both celebrating and questioning the aesthetics and the ideological baggage that came with it. But for whom? Perhaps a way to discuss his beliefs or concerns with fellow craftsman that viewed the images? Editor: It makes you wonder about the drawing's intended purpose. Was it a study for a larger work? A decorative scheme? Or perhaps, as we’ve discussed, something more subversive, intended to challenge those established norms through the very language of design itself? Curator: Yes, exactly! Thank you for illuminating those potent nuances. Editor: My pleasure; it’s fascinating to delve into the cultural memory embedded in such seemingly decorative forms.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.