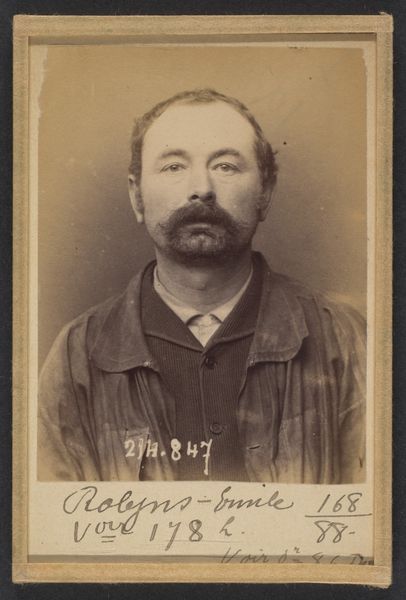

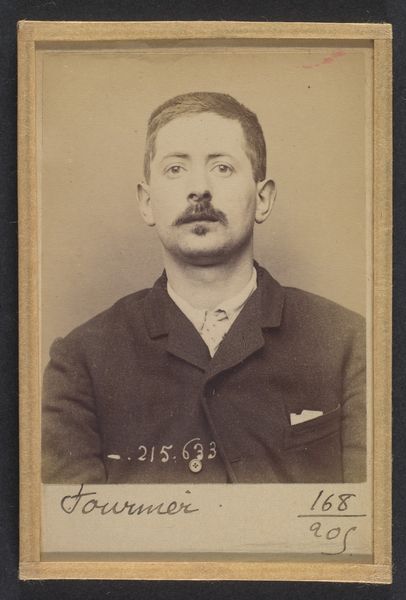

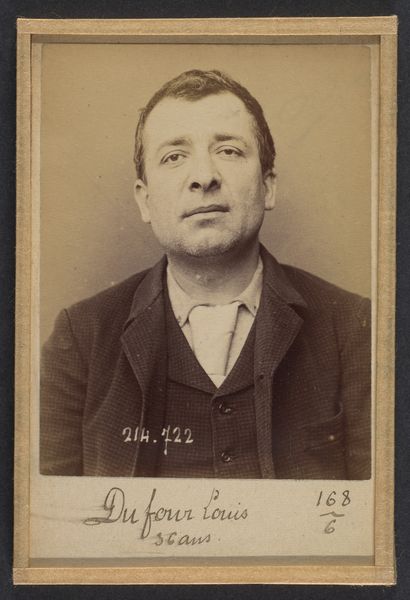

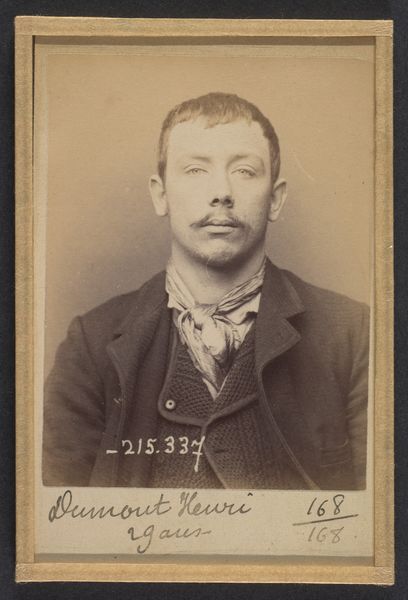

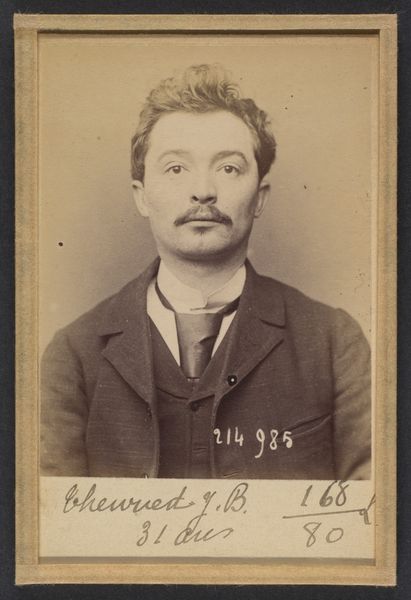

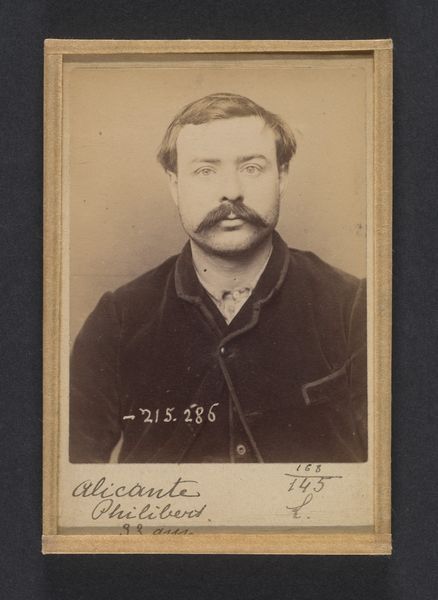

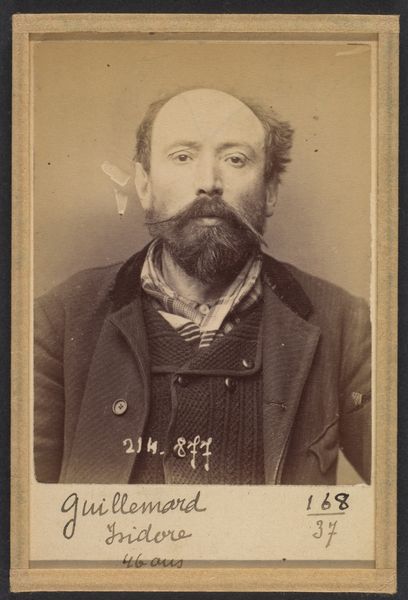

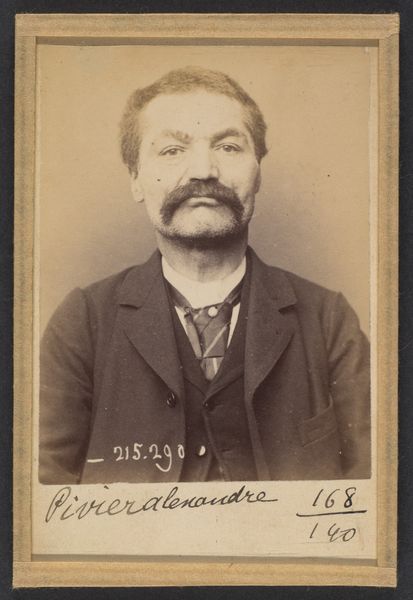

Belloti. Louis. 28 ans, né à Turin. Camelot. Anarchiste. 18/3/94. 1894

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: We're looking at a gelatin silver print titled "Belloti. Louis. 28 ans, né à Turin. Camelot. Anarchiste. 18/3/94," by Alphonse Bertillon, from 1894. The subject's slightly tilted head and the inscription indicating "Anarchiste" give this photo a defiant air, doesn’t it? How do you read this image, particularly thinking about the materials and production behind it? Curator: Well, consider what gelatin silver printing enabled in the late 19th century: mass production and distribution of images. This wasn’t high art, but rather a tool employed by the state for control. We see this portrait as an artifact of power, a component in the bureaucratic cataloging, almost the processing, of individuals deemed 'deviant'. Notice the subject, identified with precision—age, birthplace, occupation, political affiliation, date. Everything is cataloged. How does this level of documentation play into ideas about visibility and control? Editor: So it’s not just a portrait, but also a record produced for a specific purpose. It makes me wonder, where would this photograph have been seen, and by whom? Curator: Likely kept within police archives, not meant for public consumption in the conventional art sense. The labor involved extends beyond Bertillon as photographer; consider the printers, clerks, and other personnel engaged in creating and managing this vast visual database. The mass production of these images underscores a shift towards a culture of surveillance, facilitated by technology. How does knowing its archival context change your perception of the subject, Belloti, and the photograph itself? Editor: It certainly shifts it. It's less about an individual and more about a system that reduces people to data points. The physical nature of the print—the paper, the gelatin—becomes evidence of this process. Thinking about all the hands involved and the photographic processes really grounds the artwork. Curator: Exactly. By analyzing the means of production, we reveal the intricate relationship between technology, power, and the individual within a specific historical context. Editor: Thank you for shedding light on how this image operates within the context of its creation and intended use, making the materiality so relevant. Curator: Indeed, by focusing on the material and process, we moved beyond aesthetics, understanding photography's function in shaping social and political realities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.