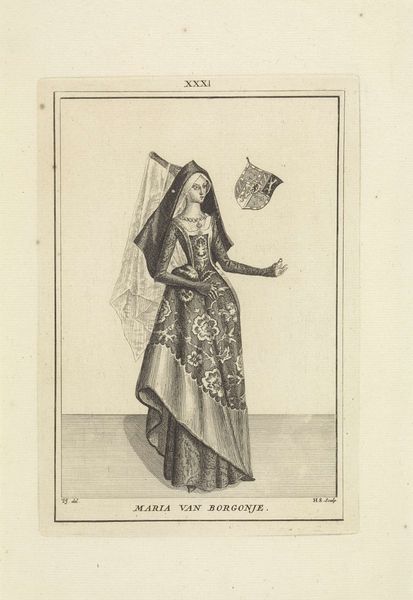

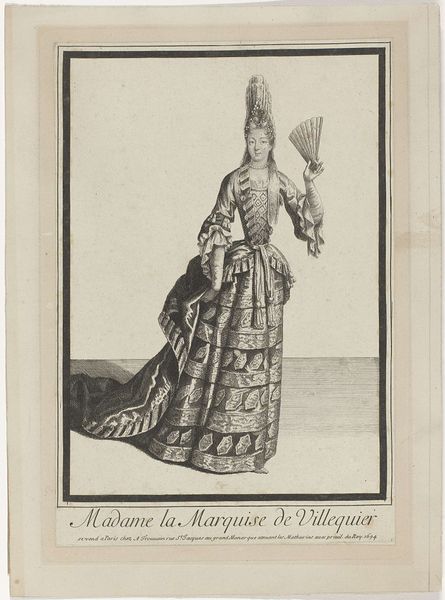

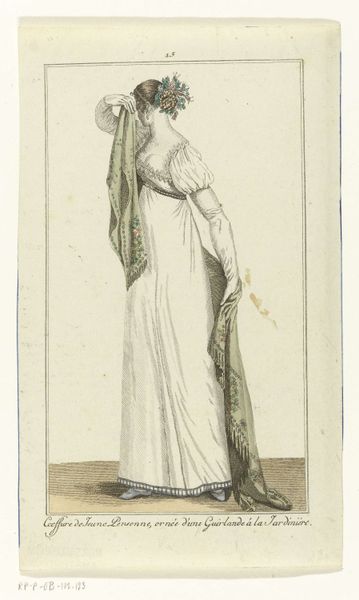

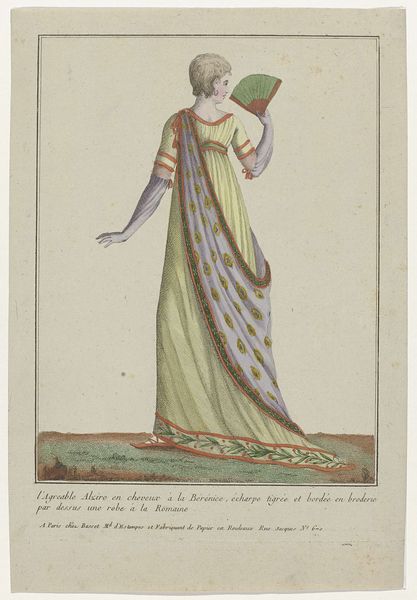

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

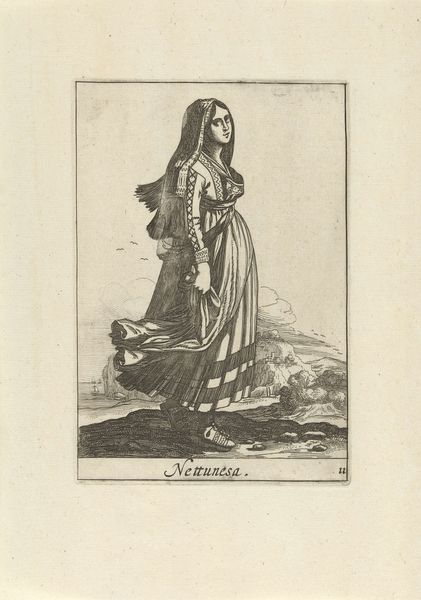

# print

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 192 mm, width 135 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Hendrik Spilman's 1745 engraving, "Portret van Ada, gravin van Holland," at the Rijksmuseum. The way she's depicted, almost floating in that gown, makes me wonder what this image was supposed to communicate. What's your read on this portrait? Curator: It's fascinating how Spilman utilizes the visual language of the baroque to portray Ada. Given that this print dates from 1745 but depicts Ada, Countess of Holland from centuries earlier, we should ask: who was the intended audience and what message did the commissioner aim to convey? Consider the context: the Dutch Republic was defining itself, and historical figures were frequently re-imagined to suit contemporary political narratives. Editor: So, you're saying this wasn't necessarily about historical accuracy? Curator: Precisely. It's less about factual representation and more about constructing a lineage, visually asserting a claim to power and legitimacy. Ada, in her opulent attire, becomes a symbol, almost an ideal of Dutch nobility and governance. Who controls the past controls the future. The engraver made other portraits in a similar fashion to circulate idealized versions of the Dutch royalty at the time. Notice how the print, as a medium, made the imagery more widely accessible than, say, an oil painting confined to a private collection. Editor: That makes me see it differently. So, it’s not just a portrait, but a carefully constructed image meant for public consumption and promoting political agendas? Curator: Exactly. By understanding the social and political backdrop, we begin to understand that art often actively *shapes* history, rather than merely reflecting it. Editor: This reframing is something I will keep in mind next time I see an old painting. Curator: Glad to provide a fresh look to what we already "see".

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.