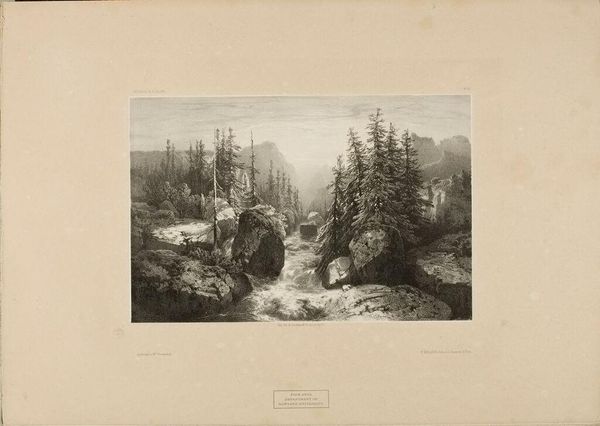

Fotoreproductie van een schilderij met de waterval van Huskvarna door A. Nordgren 1863 - 1876

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

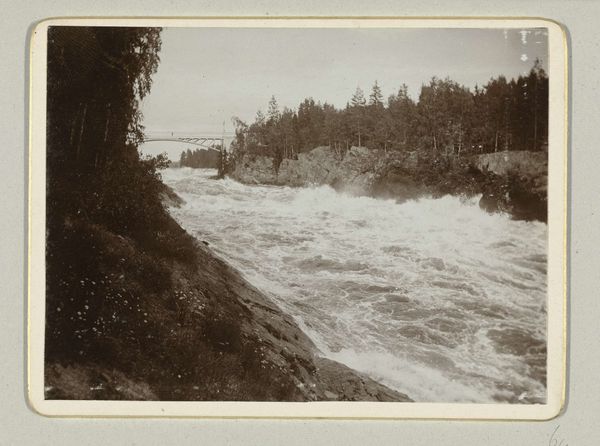

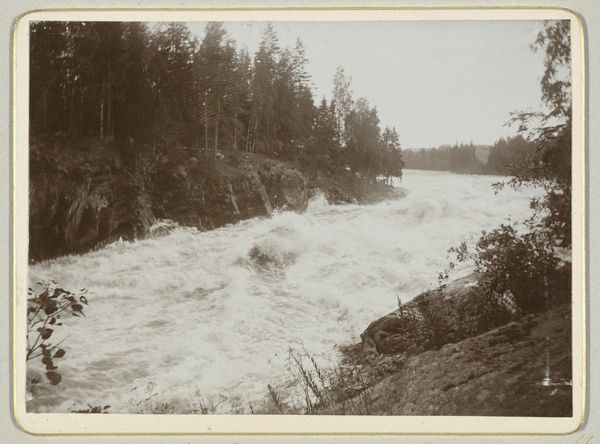

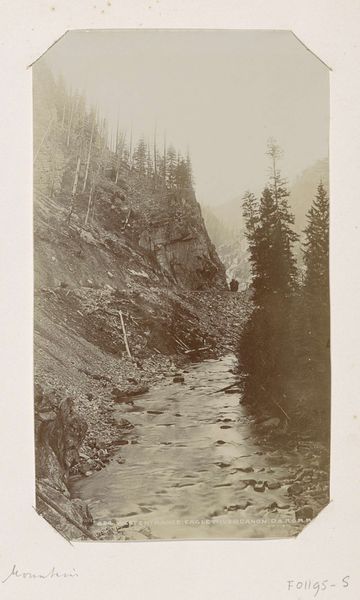

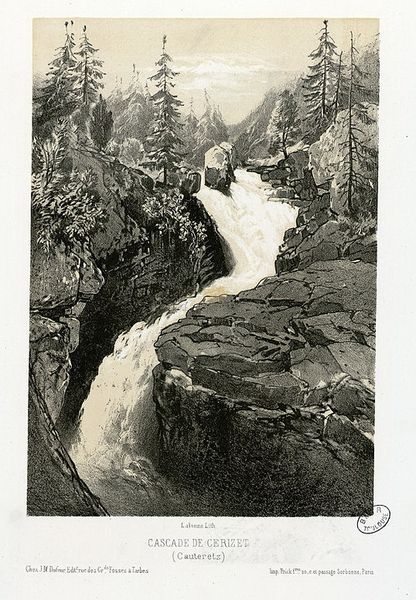

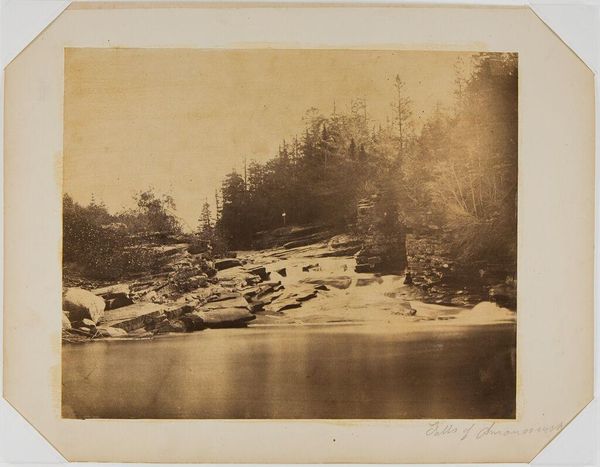

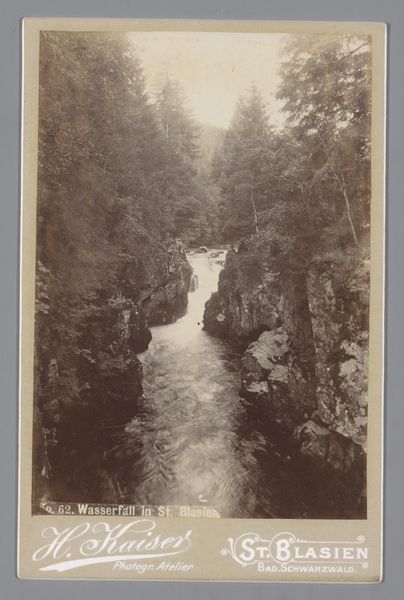

Curator: This is a gelatin-silver print, taken sometime between 1863 and 1876, titled “Fotoreproductie van een schilderij met de waterval van Huskvarna door A. Nordgren," or "Photographic reproduction of a painting with the Huskvarna waterfall by A. Nordgren." Editor: It evokes such a dramatic, almost brooding atmosphere, doesn't it? The heavy focus on water in motion, contrasted with the stark solidity of the rocks. Curator: What I find fascinating is the photographic reproduction itself. Someone took a painting and then meticulously recreated it using this relatively new medium. Think about the labor involved, the darkroom practices of the era. There are incredible questions about art making arising here. Editor: Exactly, and who was this “A. Nordgren,” the artist of the painting? This photograph makes me think about the accessibility of art at the time, too. This reproduction allowed the distribution of an image far beyond the boundaries of its original canvas. And Huskvarna itself, the landscape--what role did the natural world play in identity and artistic movements? Curator: You're touching upon critical questions regarding artistic agency and cultural dissemination in this period. Photography’s rise had a clear and powerful impact on what art meant and how people viewed it. What sort of value did that put on labor? On originality? What was seen to be the artistic component? The photo itself, or the painting? Editor: Also, looking closer, I am interested in how photographic methods shaped colonial narratives that are both romanticized and sanitized, often presenting a skewed and curated vision of land use, labor, and indigenous claims. And these photographic images end up serving complex ideological agendas of the era. Curator: Right. Consider the industrialization of the Husqvarna region at the time, particularly its metalworking factories using waterpower. Was this image offering a counter narrative to industrial labor? Was the original painting commissioned to create a myth of a pre-industrial golden age? Editor: It serves to remind us that these artistic pieces are rarely standalone. Understanding their political and social underpinnings gives us a clearer perspective not just on the art itself but on the whole period. Curator: I'm struck once more by how a photograph that depicts a landscape can contain within it so much about shifts in making, craft, and how social contexts were shifting in the mid-19th century. Editor: Yes, and how the natural landscape is more than just something scenic—it’s wrapped up in histories of labor, exploitation, and resistance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.