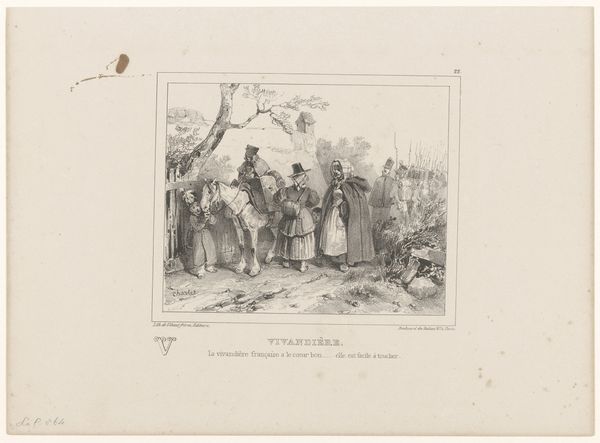

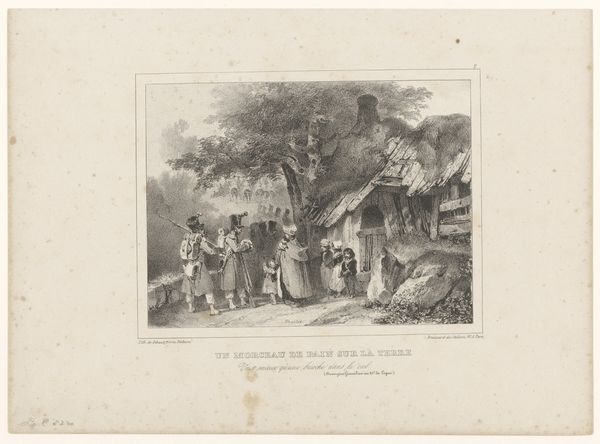

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 277 mm, width 362 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's consider this print, "Cubanen die dansen en muziek maken," or "Cubans Dancing and Making Music," a lithograph by Frédéric Mialhe, dating from around 1848. What strikes you first about it? Editor: Well, initially, the tonal range, leaning heavily towards monochrome, imparts a certain melancholy, wouldn't you agree? And the composition, that interplay of shadowed figures in contrast to the somewhat idyllic background… it feels carefully constructed to produce a distinct mood. Curator: The arrangement certainly suggests a carefully orchestrated scene. Mialhe uses symbols consciously to communicate specific social dynamics. Look, for example, at how some figures lounge idly, while others seem to labor, hinting at complex social divisions of that time. And even the titular dance could symbolize the spirit of resistance among enslaved peoples. Editor: Do you not see how the diagonal lines lead our eye towards the center of the composition? Or the texture created by cross-hatching which provides an underlying geometric structure that unifies this apparent spontaneity? There’s a method to Mialhe’s romanticism, wouldn’t you concede? Curator: Of course, technique serves to communicate cultural meanings, such as a nostalgic recollection of community—that perhaps never truly existed, right? Consider also the power dynamics imbued in this piece, representing Cuba at that time... Do you see the echoes of colonialism reflected here? The seeming idyllic lifestyle perhaps masking deeper troubles. Editor: I follow you, I only posit, if that message relies upon visual elements within the formal arrangement. Note how certain figures command a certain amount of pictorial space. Their poses evoke confidence… How, for example, does that translate beyond the lines on this page, to cultural understanding? Curator: This piece functions almost like a snapshot, holding memory through potent iconography. So when viewers come into contact with this scene they gain access, consciously or unconsciously, to our understanding of culture, society, politics. The history embedded is more than ink; it’s an entire world frozen in a moment. Editor: Agreed, indeed it makes you consider the power that lies within visual culture, its ability to speak not just through the visual elements present, but for what it communicates over decades, even centuries. Curator: Precisely, yes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.