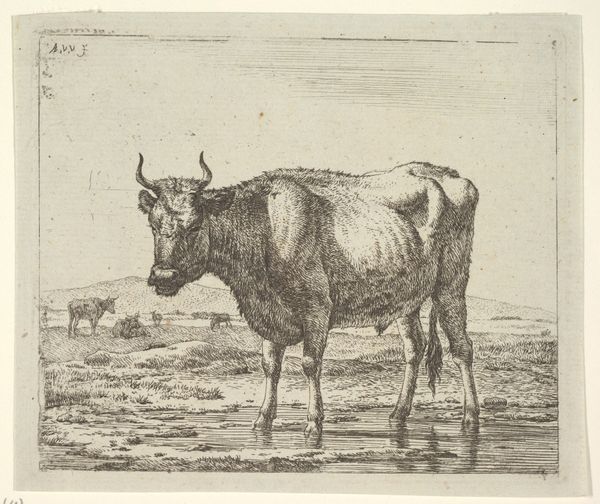

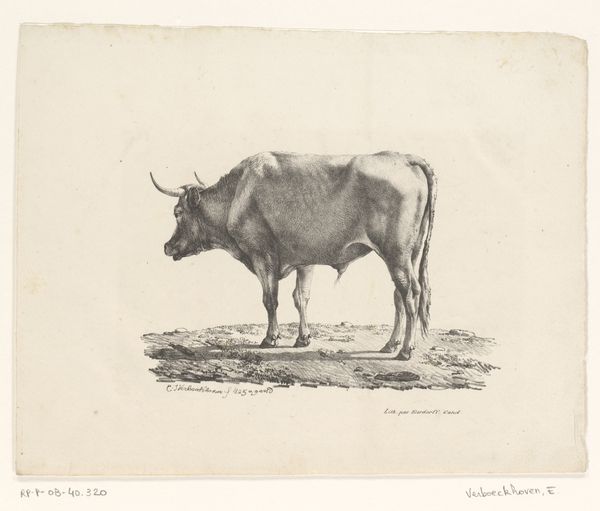

print, etching

#

animal

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 121 mm, width 133 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

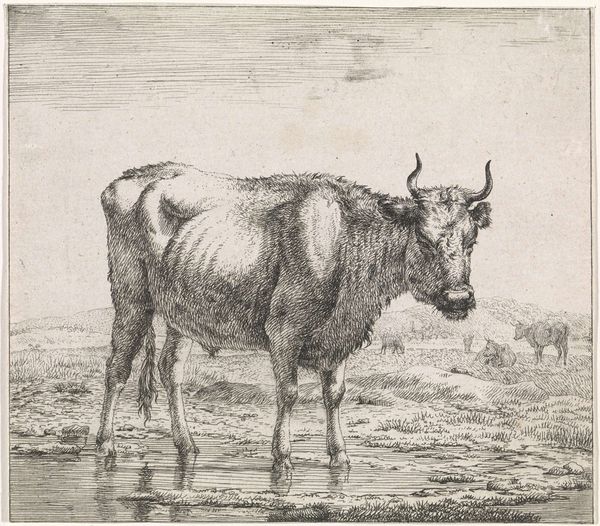

Curator: We’re standing before Eugène Verboeckhoven’s “Landschap met stier,” or “Landscape with Bull,” created sometime between 1808 and 1881. It’s currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s an etching, a print, rendering a very pastoral scene. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It's subdued, almost melancholic. The lone bull seems isolated, despite the other cattle in the distance. There’s a palpable stillness in the composition. Curator: Well, let’s consider the method. Etching involves coating a metal plate with a waxy ground, drawing into it with a needle, and then immersing the plate in acid. The acid bites into the exposed lines, which then hold the ink to be transferred to paper. Think about that physical process—the labor involved. Verboeckhoven, celebrated for his animal paintings, used this printing method to broaden distribution of his art through reproducible formats. Editor: Exactly. It also brings the conversation of ownership and value to the forefront. While Verboeckhoven attained success depicting farm animals in landscapes, one must ask about the economic landscape for those working directly in animal husbandry and agriculture during the 19th century. Consider the socio-economic realities of the working class who relied on these animals for their livelihood. Is the image romanticizing rural life or commenting on it? Curator: It's realism, certainly, but I would lean more toward romanticizing. The bull is presented almost heroically, a proud figure in its environment. The etching itself—consider the materials again, the paper, the ink, the metal plate. They represent industry meeting art, democratizing images, although access still rested on certain levels of capital, making art ownership, although expanded through print, not quite equitable. Editor: Yes, and who has the power to create and circulate these images and whose story are they actually telling? There’s something inherently political, or at least, social, in the gaze. Is the bull rendered as majestic for art’s sake or is there some underlying intention? What kind of commentary can we make regarding our relationship to nature, labor, or identity? Curator: Ultimately, “Landschap met stier” serves as a captivating lens through which to consider not only art production, but also animal representation and labor conditions of its time. Editor: Absolutely. Thinking critically about the distribution and creation helps us to reconsider its modern day impact.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.