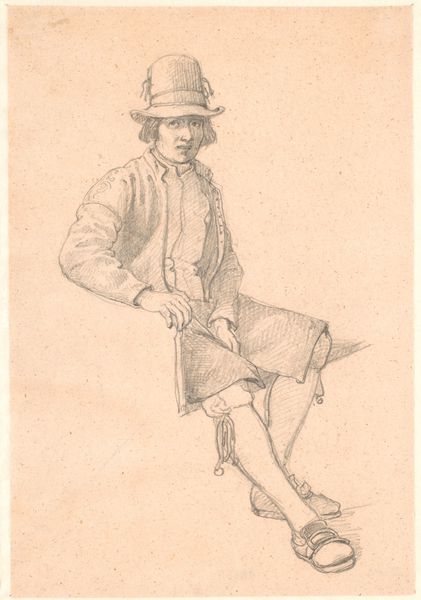

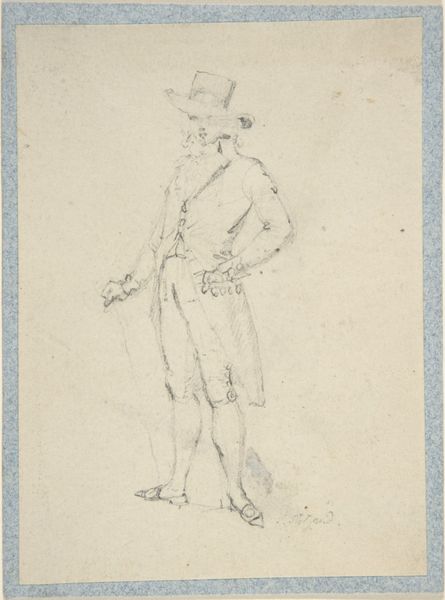

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

form

#

pencil

#

15_18th-century

#

sketchbook drawing

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 329 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have "Portrait of a Servant," a pencil drawing dating back to approximately 1780, and part of the Rijksmuseum collection. It’s attributed to Hendrik Pothoven. Editor: My immediate response is… vulnerability. There's something so soft and tentative about this sketch, a quietness in his downward gaze that makes me wonder about his interior life. Curator: It's fascinating to consider that during this era, figuration, particularly portraiture, was increasingly driven by academic art and neoclassicism. Works served specific social and political purposes. A portrait like this raises questions, doesn’t it? Whose gaze are we meant to adopt? The sitter’s, the artist’s, or perhaps the patron's? Editor: Exactly! Think about the power dynamics. It’s a portrait, but is it really about *him*, or is it about the person who commissioned or approved of the image? What was his life like, serving within a Dutch household during this era of both prosperity and increasing colonial involvement? I wonder what is on the tray, but maybe that is secondary. Curator: It also challenges the prevailing art of the time. He isn’t some lord in powdered wig finery. Here's a person who would otherwise be excluded from the annals of history represented with what seems to me like sensitivity. And this pencil sketch makes us feel a close connection to the artwork. Editor: The intimacy is undeniable, but it’s also why the history, the implied narratives around race, class, and labor, are impossible to ignore. What's missing from the story being told? Curator: What interests me further, and maybe pushes me back slightly, is how the social and cultural values of the time were embodied in even a seemingly modest drawing. It offers us a lens into how representation shaped social standing. This particular drawing sits on the cusp of major change as Europe is about to get into full swing with colonization across the world. The composition and form speak to more than the individual’s personality, offering up details of class structures. Editor: Ultimately, viewing this drawing invites a crucial consideration: Whose stories do we amplify in art spaces and how do we acknowledge those historical absences, both in the work itself, and in the museums? How does a museum today provide additional content, and engage conversations for visitors so the narratives can become more expansive? Curator: A valuable question. A work like this isn't simply a snapshot, but a catalyst to excavate the past and confront present biases. Editor: It reminds me of the power of art to provoke vital discussions about inequality and representation, encouraging empathy and awareness in how we engage with both art and history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.