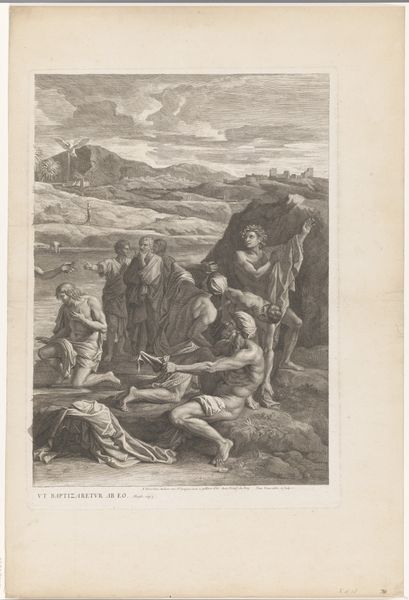

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 324 mm, width 303 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Eloquentia. Looking at this engraving by Jacques-Antoine Friquet de Vauroze, which dates somewhere between 1663 and 1716, it feels heavy, like the weight of history. It really leans into that Baroque grandeur with classical realist undertones. What strikes you right off? Editor: It feels performative, theatrical even. Stark stage lighting on these figures arranging… rocks? Like Sisyphus but with a hint of Renaissance fair cosplay. The pyramid in the back suggests grand narratives, but those tumbled stones whisper something a bit more...chaotic. Curator: The rocks are an interesting choice, aren't they? The inscription references the idea of eloquence emerging from stones, linking it to Mercury, or Hermes, whose caduceus—that staff entwined with snakes—he extends towards the seated figure. Mercury in his capacity as conveyor of persuasive and rational language touching this older man wrapped in classical robes. There's something happening right on the cultural edge where new rhetoric is built from archaic roots. Editor: Exactly! So is it about elevating wisdom? Or, maybe the engraving wonders if wisdom needs that divine *spark* of eloquence to really mean anything? Curator: Both, and more! In Baroque art, allegory reigns. It makes me think about rhetoric's place in shaping society and influencing our actions—that even a seemingly simple image could become this carefully constructed argument meant to be debated. Editor: This isn't a passive experience; this *becomes* an intellectual sparring match through imagery! Still, those stones ground it… reminding me, even persuasive words begin with gritty, uncomfortable realities. Curator: I think it speaks to how classical symbolism and allegorical representations really tried to provide an intellectual language across cultures. The idea of "eloquence" or persuasive argument touches human civilizations regardless of context. Editor: Right—it feels almost brave how this print embraces nuance. Makes me consider my own rhetoric—what rocks am *I* carrying, and how could they become something more? Curator: Precisely. And isn’t it incredible that a work made centuries ago can still provoke those kinds of questions in us today?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.