photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

still-life-photography

#

desaturated colours

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

photography

#

natural colour palette

#

desaturated colour

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

Copyright: Public Domain

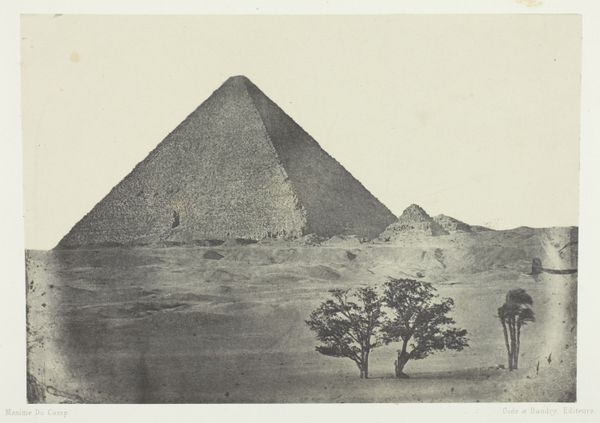

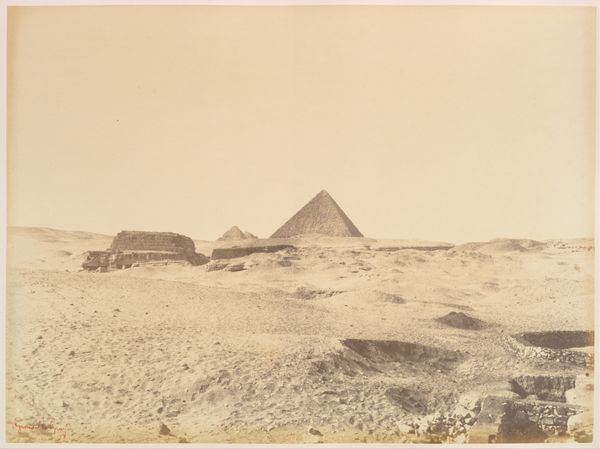

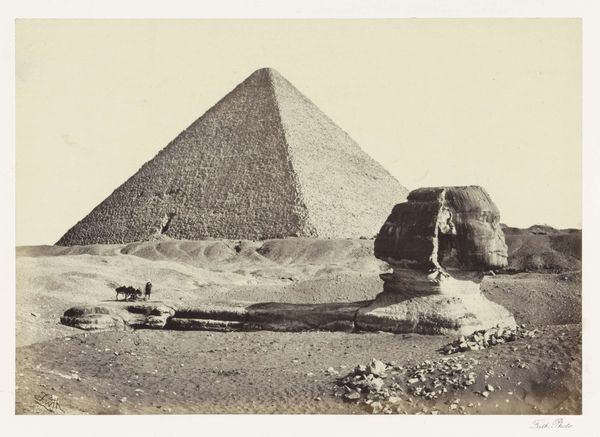

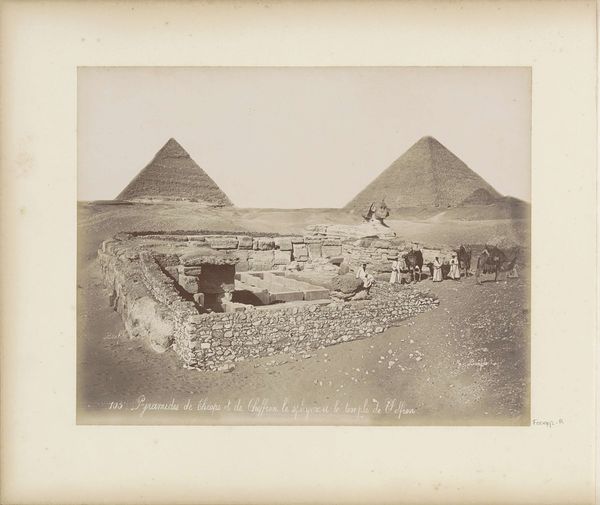

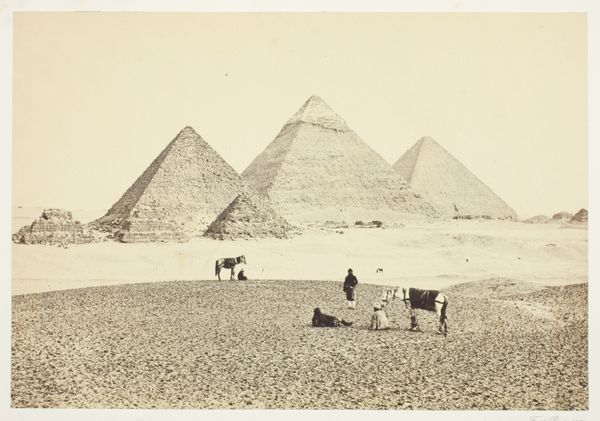

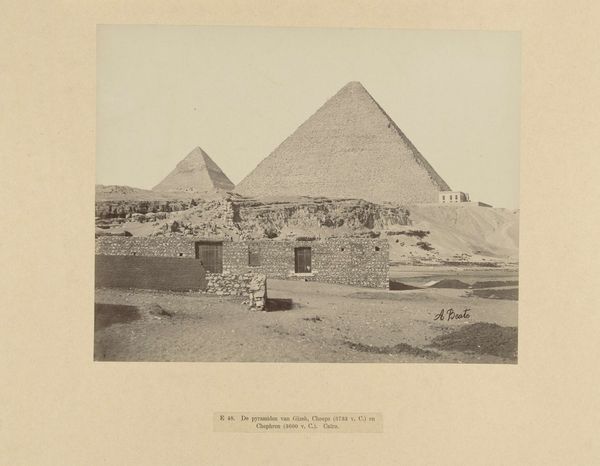

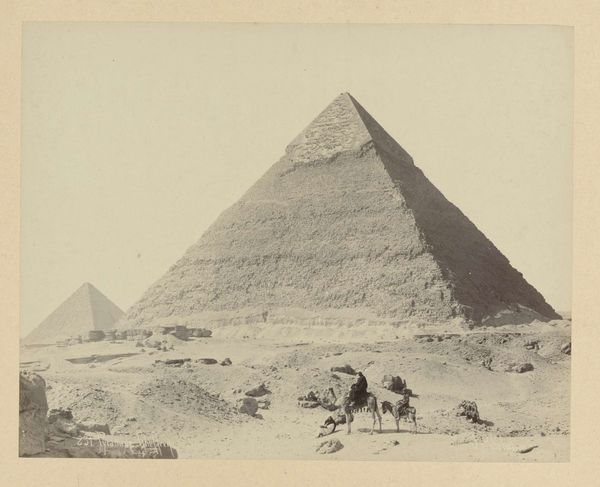

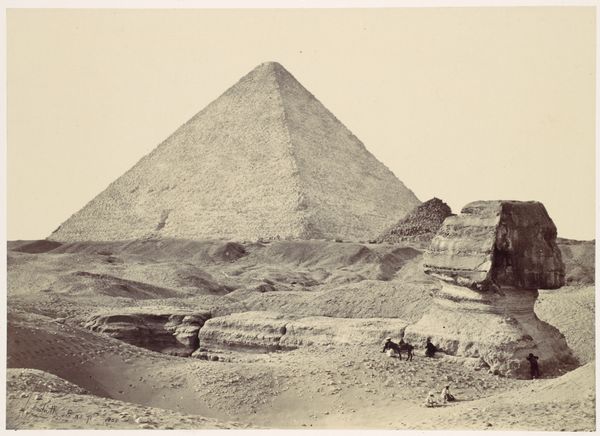

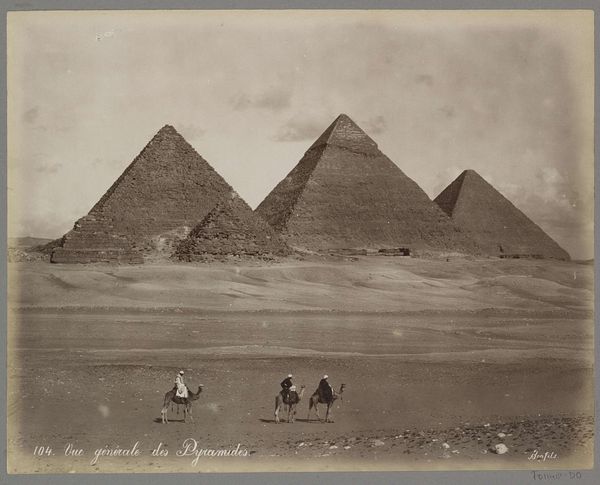

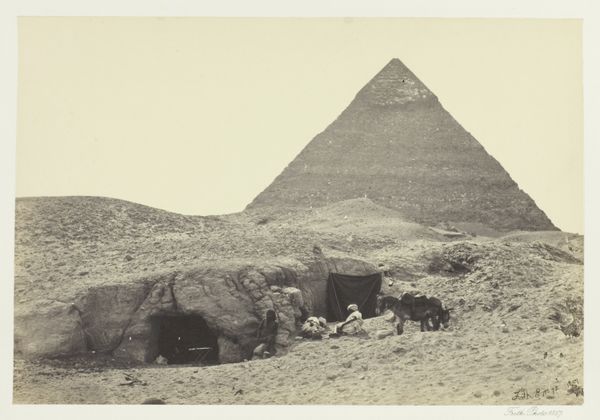

Curator: Maxime Du Camp’s 1850 gelatin silver print, Égypte Moyenne. Pyramide de Chéphren, captures the grandeur of the pyramid and its surrounding structures. Editor: Striking. The starkness and the desaturated palette almost feel lunar. The play of light on the stones hints at the enormous physical labor involved. Curator: Exactly. Think of the societal and economic forces needed to mobilize that workforce, the sheer materiality of extracting and transporting those colossal blocks! The photograph highlights not just the artistic achievement, but the social structures enabling it. Editor: And how the eventual framing of it is brought to the Western World, where wealthy individuals might travel or experience images of ancient grandeur like this through these novel portable prints. I mean, look at its exhibition history - the photograph itself becomes a cultural object, exhibited, studied, and collected, a far cry from its original context. Curator: True. Photography served a powerful colonial function, disseminating images that fueled Western narratives. But consider the technical process, too – the wet collodion process Du Camp employed required immense skill and preparation. Each print signifies not only subject but labor and chemistry in the service of imagery. Editor: The reproducibility of it through this particular industrial process really alters art-making in many ways, the narrative changes, the intent. Here, the photographer almost takes on a role of cultural translator or broker, in a way. And these monuments become less objects of veneration, more things that are traded and collected. Curator: A valid point, though I also believe these early photographs offered Europeans encounters with monuments otherwise unimaginable. A shared visual experience of humanity’s collective history. Editor: In the end, that shared experience, however problematic its origins, leaves us today with images that encourage thoughtful discourse about artistry and empire, labour and leisure, still being constructed, always in progress. Curator: Precisely. This work serves as a historical record, inviting us to investigate both the artistic process and the forces that have shaped how we perceive history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.