painting, watercolor

#

water colours

#

painting

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

intimism

#

abstraction

#

modernism

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 200 cm (height) x 154 cm (width) (Netto)

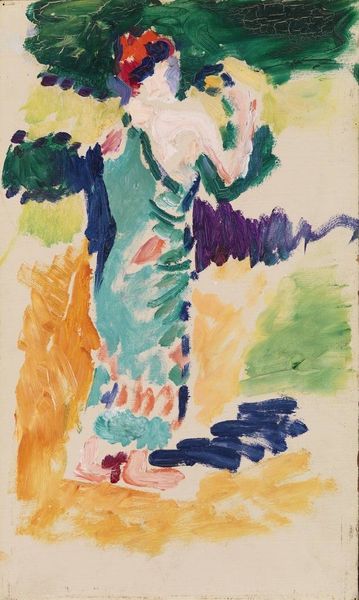

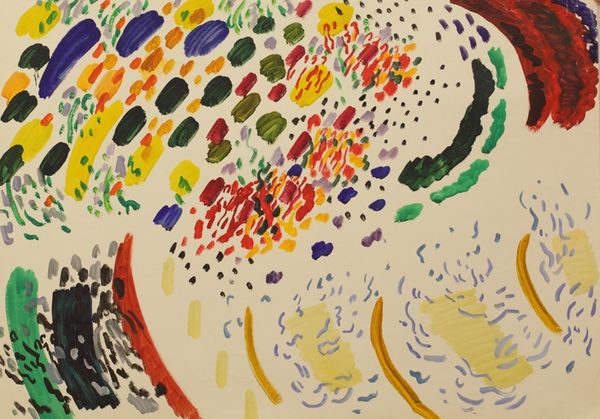

Curator: Here we have "Faun and Nymph" by Edvard Weie, crafted between 1940 and 1941. It’s a striking watercolor painting currently housed here at the SMK. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: The forms feel fragmented, almost dreamlike. The palette is subdued, but there's a dynamism, like a memory trying to surface. Is that truly supposed to depict a faun and a nymph? I feel there is so much more. Curator: Well, what strikes me is the interplay of material and form. He used watercolors, a typically delicate medium, to create these powerful blocks of color. Look at how the water stains the paper and lends to the work’s ethereal appearance. It contradicts the weight of the figuration in a very interesting way. How do the iconographies function here? Editor: Exactly. If we accept these forms as a faun and nymph, they immediately call up centuries of associations: wildness, nature, sexuality, the Golden Age...but they are represented through this screen of fragmented color. The choice to almost obscure those figures creates tension. Are they hidden, repressed, or simply dissolving into memory? Curator: It certainly obscures any specific classical narrative, perhaps purposefully distancing itself from earlier artistic traditions. Weie seems focused on the act of depicting those ideas through color itself, more than on simply depicting the subject matter, right? Editor: Yes. The blocks of colour could be said to represent emotional states or a disruption in memory that allows the themes associated with nymphs and fauns to be newly revisited, or reconfigured in new forms. What does the physicality of these watercolors tell us about the moment of creation and labour in its production? Curator: As I see it, the liquidity of watercolor allowed Weie a level of spontaneity in his artistic labor, right? Each stain, each blending of pigments reflects not only conscious design but also the unpredictable behaviour of the medium, embodying a dance between artistic intention and the material world’s autonomy. We can thus imagine Weie fully absorbed in its materiality as it both reflected and directed his choices in pigment, touch, pressure and gesture. Editor: This truly opens it up beyond a simple figural representation and enables the themes to persist on their own beyond specific time and place. Curator: Indeed. Weie pushes against the confines of any singular, fixed meaning. Editor: Which offers so many possibilities for future viewing. Thank you.

Comments

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

Faun and Nymph is the latest and most famous of Weie’s large-scale compositions. The picture was created in the summer of 1941, the last of Weie’s active years as an artist. It marks the end of his lifelong work with mythological and literary motifs. Faun and nymph united Weie got his subject matter from Paul Cézanne’s (1839-1906) painting The Abduction from 1867, but it also ties in with his own earlier mythological pictures where fauns and nymphs appear as the main characters. Here they are united: the faun, his back to us, carries his beloved, a nymph, towards the sea and the sky while she rests, yielding, in his arms. Pure harmonies of colour The idea for the landscape with the road leading towards the sea comes from Weie’s own landscape Mindet, Christiansø from 1912. In this late picture, however, the landscape has been simplified. The green leaves of the tree have been depicted as an almost crystalline structure composed of stringently defined fields of colour. All lines lead to the couple in the middle, drawing them into the picture: from the earth to the sea and further on into the sky. The picture marks the culmination of Weie’s ambition to compose a picture consisting entirely of pure harmonies of colour, serving here as accompaniment to an ideal image of the world where man and woman are united, where matter becomes spirit.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.