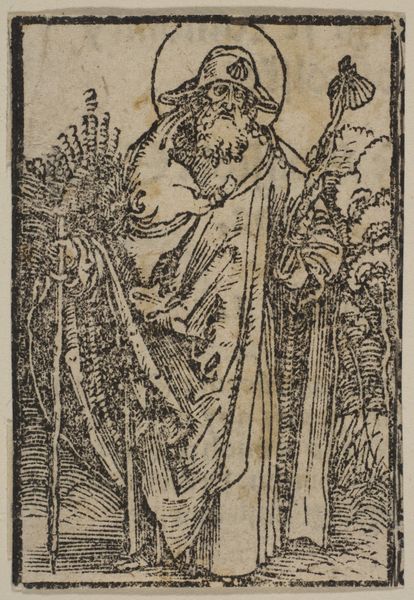

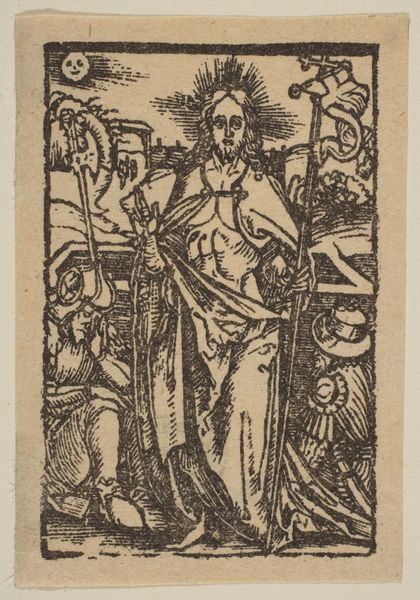

print, woodcut

#

medieval

#

pen drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Here we have a late medieval woodcut, Saint Hugo of Grenoble, created sometime between 1460 and 1480. Note the distinctive use of line to describe form. Editor: It’s a stark and somewhat eerie image. The dense, dark lines against the aged paper give it a kind of weight. There’s a roughness to it; it feels quite handmade. Curator: Absolutely. Considering its likely purpose as a devotional print for mass consumption, this artwork highlights the ways in which images circulated and shaped religious identity in the late medieval period. Hugo’s depiction in bishop's garb emphasizes hierarchical power and also symbolizes the perceived holiness inherent to this societal position. Editor: That mass production element really changes how we engage with the artwork, doesn't it? The use of a woodcut, this relatively accessible printmaking method, shows an interesting transition in the relationship between maker and consumer, and how this image spread beyond elite circles. How did they create this intensity of black through that method? Curator: The deep blacks resulted from carefully cutting away the wood matrix to leave only the lines of the image. These early prints served as prototypes and helped in standardizing saintly figures and narratives for didactic purposes and for solidifying power structures in religious life. Editor: And look closely, the details become compelling in that process. The strange cloudscape above, those sharply etched stars beside Hugo. The medium enforces this potent sense of linear detail and stark contrast; it lacks nuance, which maybe underscores the black and white moral codes of the time? Curator: It speaks to a particular understanding of representation, certainly, one where symbolic weight is often preferred over realism. The depiction of St. Hugo connects to narratives around ideal masculinity and clerical authority, ideas that impacted everything from familial structures to political order. Editor: So the medium here does become part of the message. You start thinking about the material processes required to make many copies of this intense image—a multiplication that serves as its own commentary. It almost doesn’t matter who the artist was. What matters is what these materials *did.* Curator: Right. By considering this image within a network of social, economic, and ideological forces, we can interpret this single image as both representative and generative of larger cultural meanings and inequalities of that era. Editor: It’s a powerful, disquieting little print, revealing how process and production shaped what and how we believe.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.