painting, watercolor

#

portrait

#

water colours

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

miniature

#

watercolor

#

realism

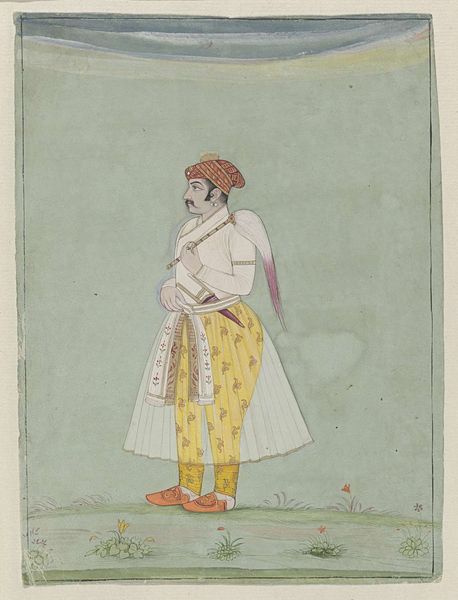

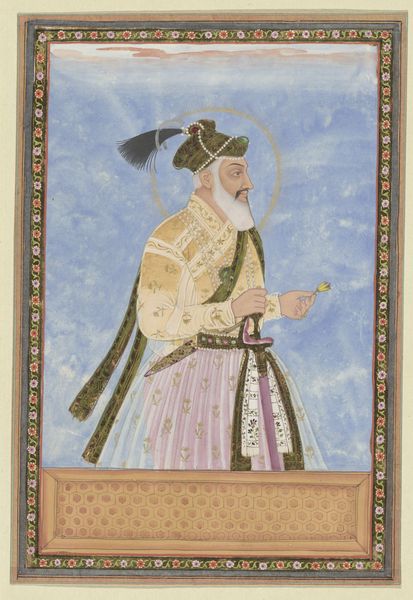

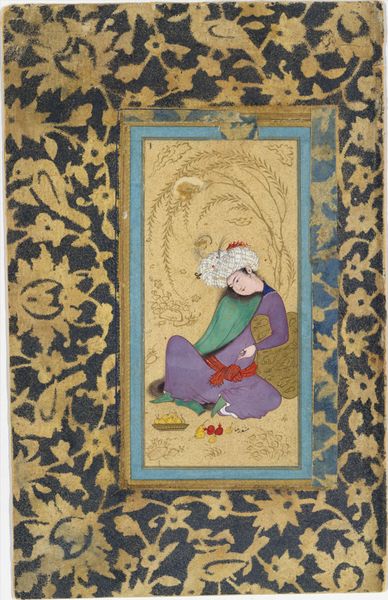

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 136 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by how intimate this portrait feels. The pastel shades and almost dreamlike quality bring this historical figure very much alive. Editor: Indeed. This watercolor piece, dating roughly from 1700 to 1710, is entitled "Portret van Akbar, staand, met verenpluim in de hand," which translates to "Portrait of Akbar, Standing, with Feather Plume in Hand," and is attributed to Gangaram. It offers a glimpse into the Mughal era through the lens of portraiture, capturing Akbar as he stands. I can’t help but consider the weight of imperial power represented in such a delicate medium. Curator: Oh, absolutely, the watercolor softens the edges, giving the emperor a strangely approachable vibe, not at all what I imagine royal portraits are usually about! His hand with that feather; he almost looks like he's about to tell a story. It’s magical how it gives you an emotional link to a person from so long ago. Editor: That softness is deceptive. Consider that in the early modern era, portraiture served as a crucial tool for constructing and disseminating imperial ideologies. Watercolors might suggest gentleness to us now, but within the historical context, such portraits actively solidified Akbar's authority by immortalizing him within a visual culture. This presentation flattens not just artistic technique but how ideas of rule and masculinity get crafted and circulated. Curator: Perhaps it’s my overly romantic idea of history clouding my vision, but the artist Gangaram had his own lens, too. Do you think the way he handled the light around Akbar's head, that almost halo, hints at something other than brute power? There’s some kind of deep admiration there. Editor: Absolutely. However, the portrayal of Akbar with what appears to be a halo needs to be deconstructed with care. Such symbolism intertwines power and divinity and draws from complex visual traditions intended to position rulers within certain frameworks of veneration and control. It is a reminder that portraiture, particularly that of leaders, involves deliberate messaging tied to claims of power. The question for me is less about personal sentiment and more about political agenda embedded in its artful design. Curator: This completely changes the way I see this piece. I guess art never rests, right? Even a feather plume is more complex than you’d think! Editor: Exactly. By bringing a critical approach, we acknowledge and unveil its function and inherent politics within historical circumstances, inviting new interpretations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.