#

landscape illustration sketch

#

amateur sketch

#

light pencil work

#

quirky sketch

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

incomplete sketchy

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

initial sketch

Dimensions: height 237 mm, width 292 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

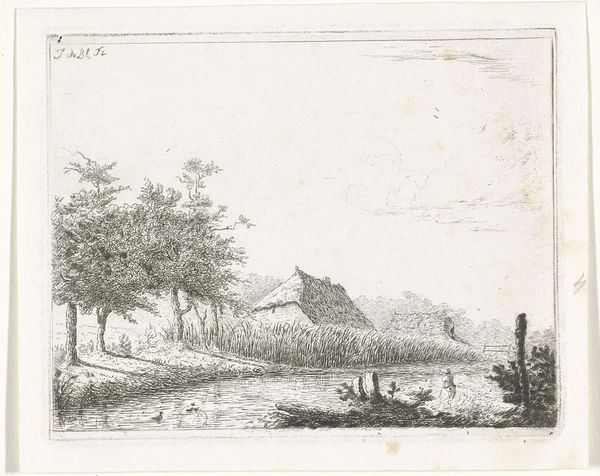

Curator: The textures and lines in this landscape pull me right in. There is a beautiful interplay of precision and looseness that speaks to artistic study. Editor: This is Anthonie Waterloo's "Boerderij aan het water," or "Farm by the Water," created sometime between 1630 and 1663. Currently it is held at the Rijksmuseum. Look closely at the textures of the foliage and reflections on the water; how do you think Waterloo achieved these effects using only pen and ink? Curator: He’s truly playing with depth by varying the linework and weight. But consider how class intersects with the landscape. Even this seemingly bucolic scene speaks to labor, land ownership, and the social structures embedded within the Dutch Golden Age. Where is the community depicted within the frame, and how might the labor systems of the time inform this artist's choices? Editor: It makes me wonder about the paper itself—was it locally sourced? Who made it? We know Dutch paper production thrived during this period due to trade and the availability of linen rags. Understanding these networks of production is key. Consider also how the reproducibility of an engraving democratized images; however, it was also implicated in capitalist modes of distribution and value extraction. Curator: Precisely! The context is never neutral. Who gets to represent whom, and for what audience? Does this artwork challenge or reinforce the social hierarchy of the time? We can read subtle hints of how society and the act of engraving shape the narrative in the seemingly still depiction of landscape. Even in what feels so open and accessible to the modern eye. Editor: Right, by considering the materiality and distribution of prints, we gain insights into 17th-century artistic labor and broader socioeconomic shifts that often disappear from traditional art narratives. Seeing the physical elements provides a strong counterpoint to interpretations confined to style or subjective intention. Curator: Well, it's a starting point for understanding what this scene, and art in general, has to say. There’s always a conversation between what's presented and the unsaid, the conditions that shaped the artwork, and what shapes our understanding. Editor: An invitation to contemplate the labor involved and question whose stories are woven into each stage of an image's life. Thanks for considering production and history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.