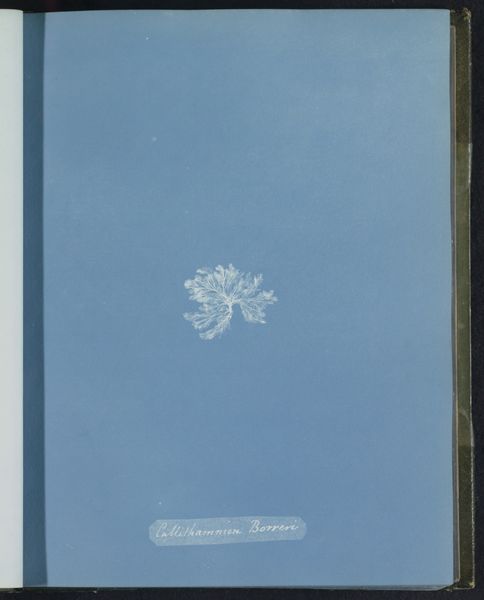

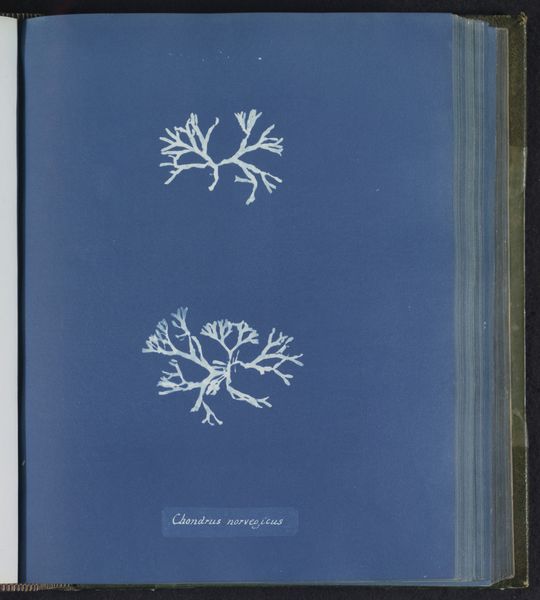

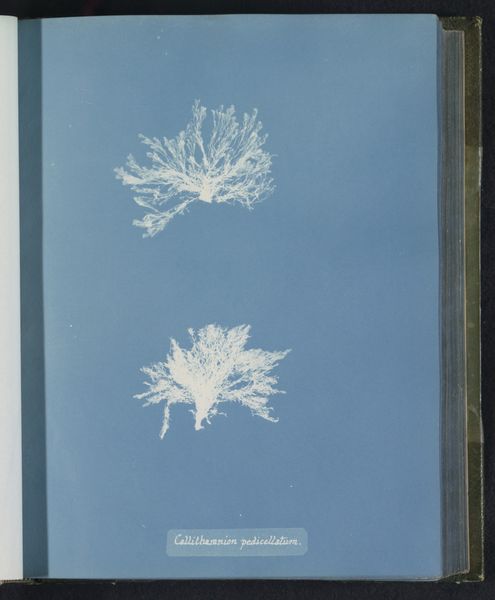

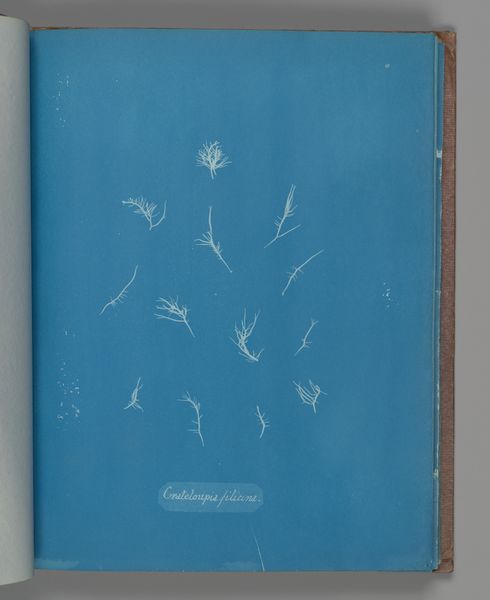

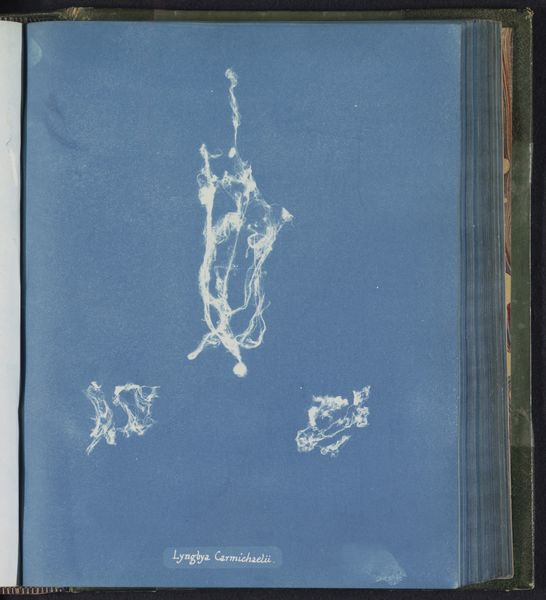

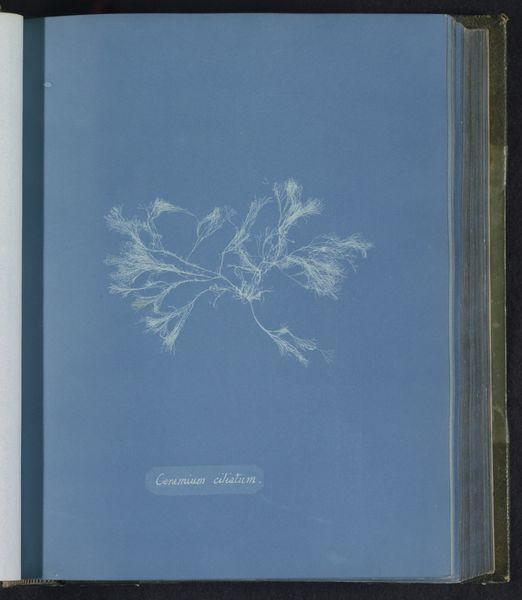

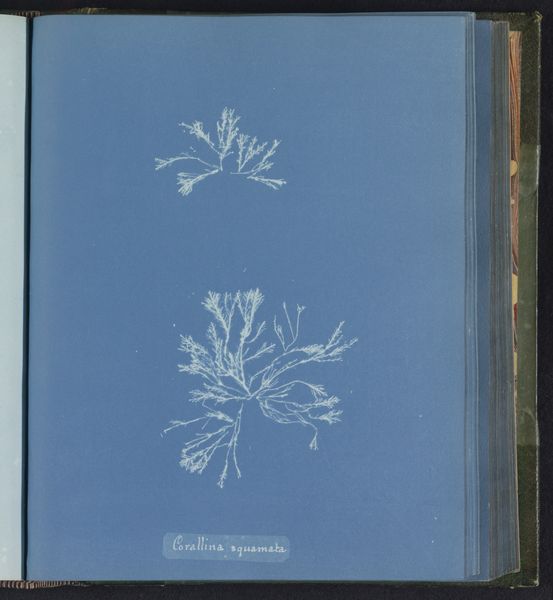

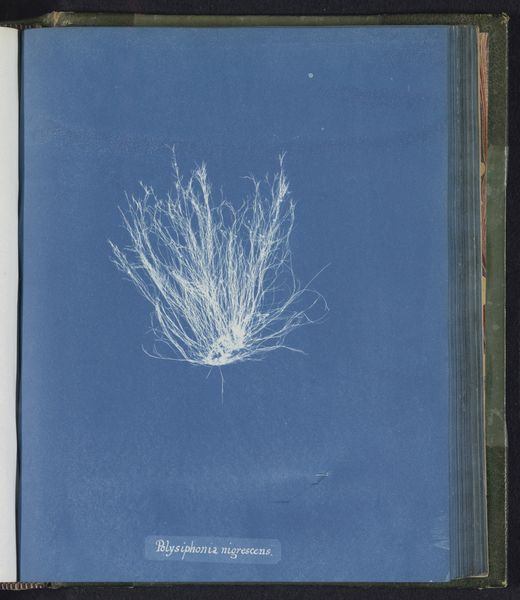

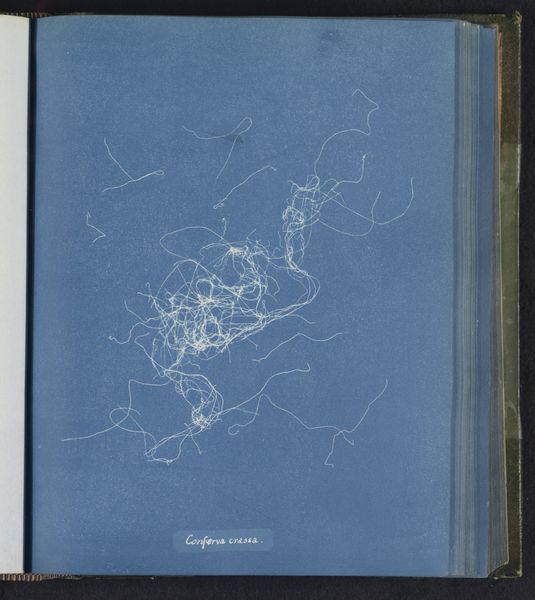

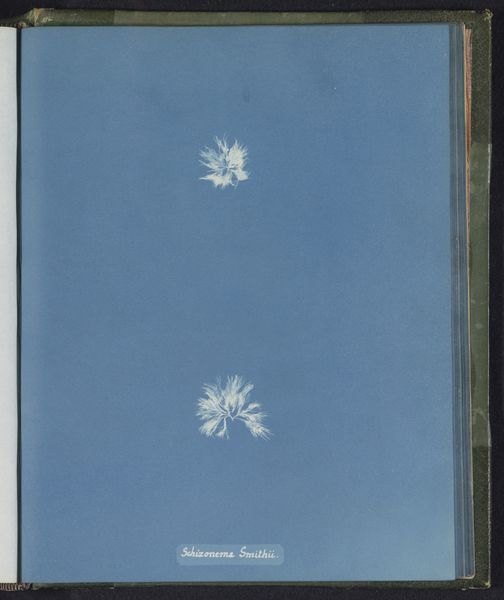

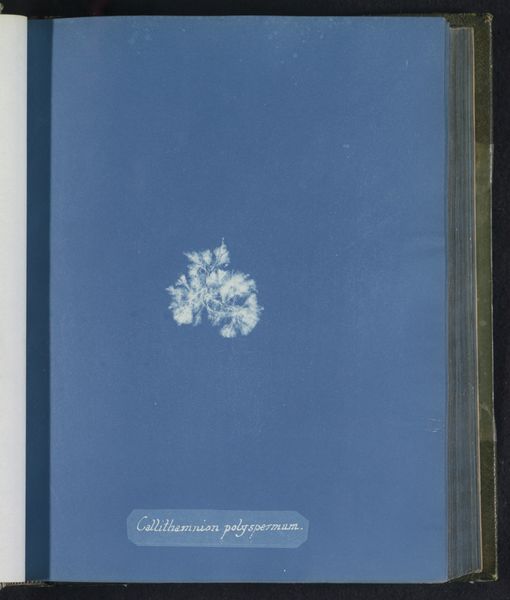

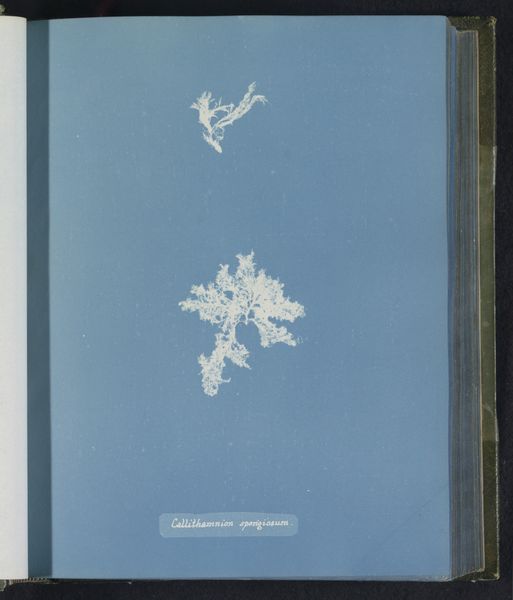

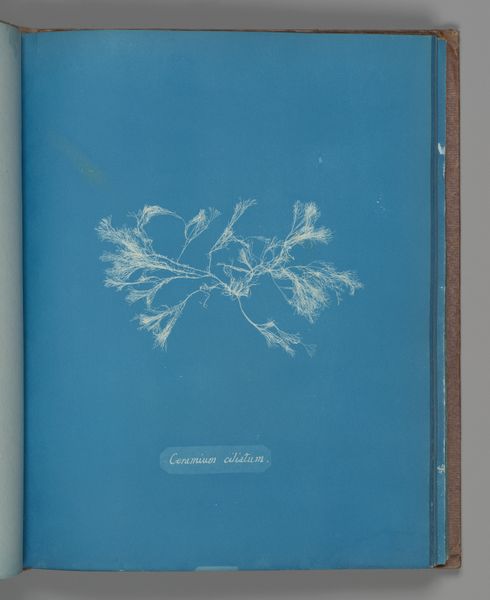

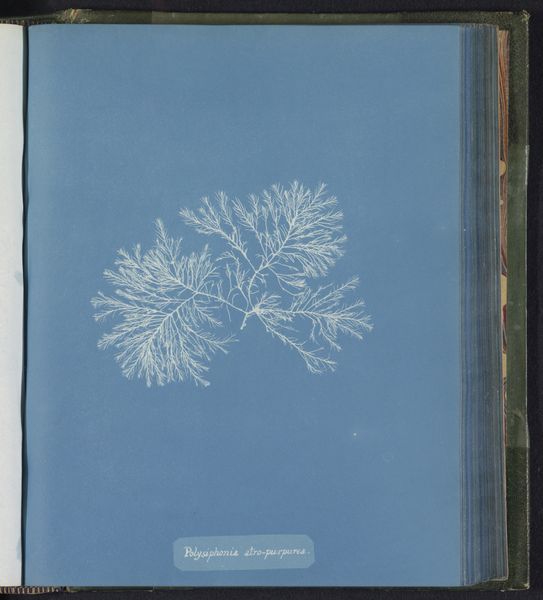

print, cyanotype, photography

#

still-life-photography

# print

#

cyanotype

#

photography

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Ah, yes, here we have "Batrachospermum atrum & Batrachospermum moniliforme" made sometime between 1843 and 1853 by Anna Atkins. What a beautiful cyanotype print! Editor: Cyanotype. Sounds like a mouthwash. Anyway, I see delicate lace against deep sky-blue. Makes me think of Victorian mourning jewelry. Did they do photography of the dead then? Curator: They did, actually. Atkins was a botanist who used this new photographic process, cyanotype, to document algae specimens. It's one of the earliest examples of photography, and she was documenting science, not sentiments! It's actually considered the first book illustrated with photographic images. Think about the scale of ambition! Editor: Ambitious! I see ethereal ghosts of seaweed. It's almost sad somehow, this vanished world caught in a chemist's blue dream. The starkness… it makes the delicate structures appear even more fragile, like capturing whispers before they fade completely. Curator: And this whisper, as you call it, really amplified access to a kind of scientific understanding. The original cyanotypes were made to illustrate her publication, "British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions," giving access to new ways of seeing the botanical world. Cyanotypes allowed scientists from different places to study her meticulous observations, not in written descriptions but rather faithful reproductions of plant life. Editor: Ah, but don't you think art is about MORE than access to something? Isn't there always something ineffable, like the artist's perspective shining through all those scientific details, changing them… transforming? Even in the most utilitarian pursuit there's a bit of artistic spirit peeking around. And, dare I say it, this artistic intervention might enhance how we perceive or "access" the subject? Curator: Of course, Anna Atkin’s hand is in it, especially as photography itself would change radically across the later nineteenth century, and especially because Atkins published a limited number of copies on her own dime. We could see it as a unique, almost artisanal endeavor, given the larger historical context. Editor: Alright, well put. Seeing it as an artistic "making" versus an assembly-line photograph is indeed revelatory here. Thanks for shifting my view there. Curator: My pleasure! The photograph helps to bring what is hidden in our world a bit closer to us. Editor: So, that "access" argument doesn't feel quite as...bloodless now. These dreamy cyan hues might be inviting, yes, perhaps into the deeper end than otherwise imagined!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.