Dimensions: height 263 mm, width 202 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

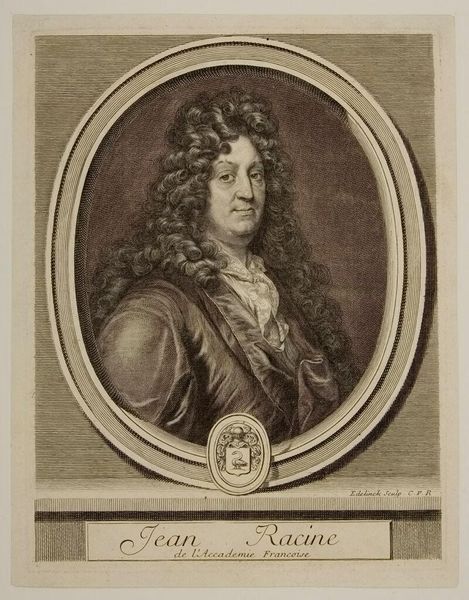

Curator: The etching we’re looking at is entitled "Portret van Pierre-Vincent Bertin," dating sometime between 1829 and 1845, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. What’s your first impression? Editor: Immediately, I am struck by the extravagance of the wig. The sheer volume and curliness scream status and perhaps a certain degree of vanity. It frames the face with a dramatic flair. Curator: Absolutely. Think about the cultural significance of these portraits, mass-produced through engraving techniques. They offer insights into how images and their symbolic value were distributed and consumed. These prints allowed the burgeoning middle class to participate in constructing their own narratives of power. Editor: Indeed, the wig is fascinating from a purely iconographic perspective. It signifies belonging to a specific elite social strata, power, intellect, and perhaps even moral virtue in that period. Look how carefully the curls are rendered, creating texture with such precise labor. Curator: Exactly, this is where it gets really interesting. The engraver's labor to recreate this luxurious aesthetic translates to social mobility. Every line incised represents countless hours mastering their craft, hoping to ascend the socioeconomic ladder. Each engraving bears the traces of their physical labor in producing these desirable markers of status. Editor: And that physical act of meticulous, repeated engraving becomes a metaphor, doesn’t it? It embodies a collective striving towards status. Also consider the sitter's face. There's a hint of world-weariness there; a melancholic depth contrasting the external opulence. Do you think he is conscious of the gap between the projected image and himself? Curator: An excellent point. The printing process itself involved layers of physical and chemical processes—the copper plates, acids, inks all required resources, trade and human actions, the division of labor that made such production possible at all. What survives in the final object is a highly distilled embodiment of that historical production. Editor: Looking closely, the oval shape emphasizes the enclosed nature, almost as if the image is precious cargo held inside a vessel. We project so much now by viewing through a rectangular lens and there’s something uniquely precious in this constrained, almost claustrophobic frame. It truly directs the viewer toward an almost idealized face. Curator: So, in the end, it isn’t just about a pretty picture, is it? It is the product of intense social labor and material conditions, the etching becoming both artifact and agent of social mobility. Editor: Yes, it embodies the complex play between the man, his symbols, his representation and all the associated cultural meanings they entail.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.