drawing, print, etching

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

toned paper

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

sketch book

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

history-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

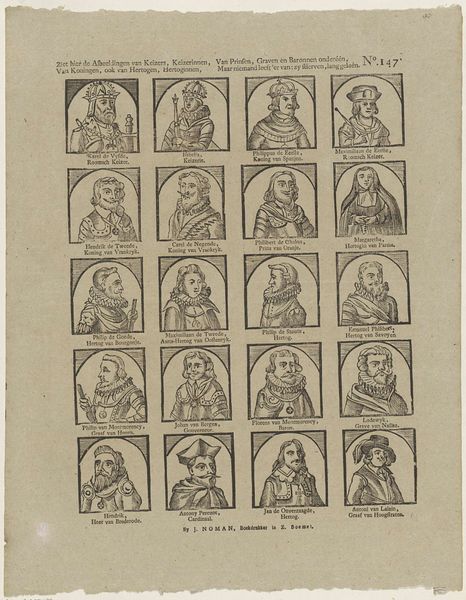

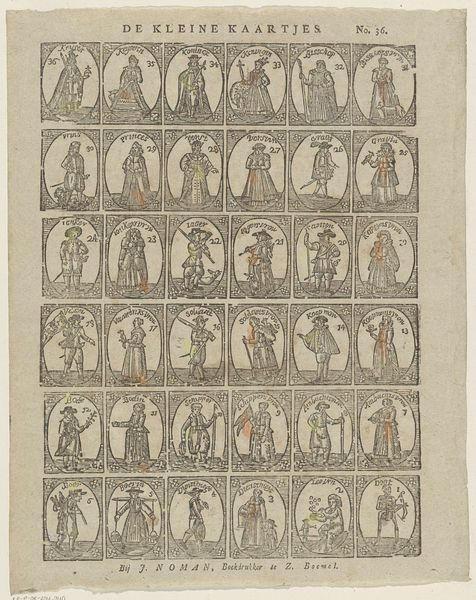

Dimensions: height 400 mm, width 327 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

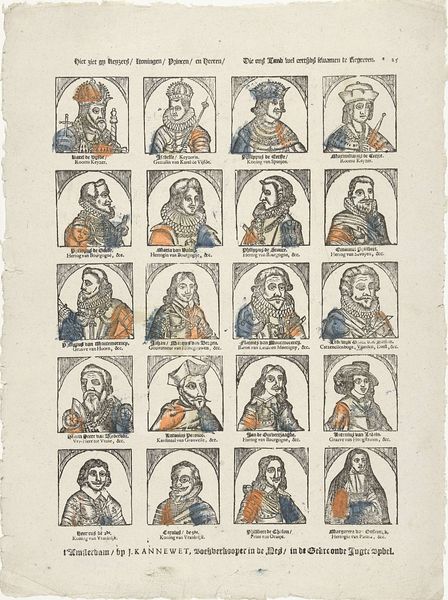

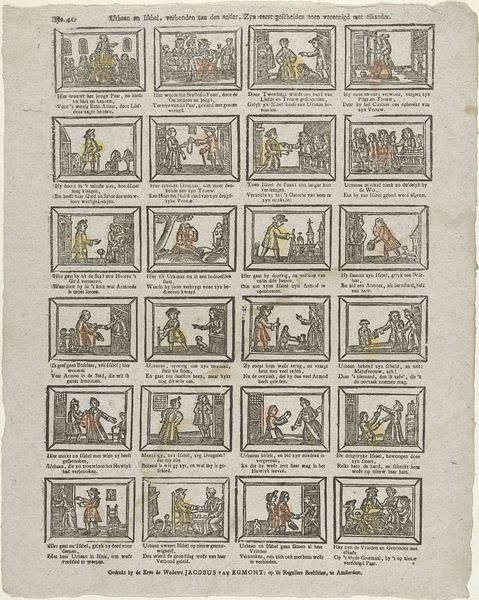

Curator: Looking at this piece, “Vorsten en vorstinnen” – “Princes and Princesses” – made sometime between 1806 and 1830 by Johan Noman, the initial impression is of something almost mass-produced. The regular grid of portraits gives that feeling. Editor: It definitely has the look of printed ephemera, something you’d find distributed widely. It's an etching on toned paper, almost like a page torn from a sketchbook. There's a rough quality to it. What were its means of production? Curator: Precisely! Noman's technique involves etching and probably some printmaking. The visible plate marks and the uniformity suggest a deliberate effort at replication, at dissemination. We know the materials are basic, likely chosen for accessibility. It’s almost crude, isn’t it? Not the fine lines we usually see associated with depictions of nobility. Editor: Right. So it’s deliberately subverting the high-art treatment usually afforded to rulers. This challenges conventional perceptions of portraiture as exclusive and aimed only at an elite class. Consider the implications, it shifts the act of portraiture into popular consumption, creating accessible depictions that impact cultural identity. How was Noman’s work received in its time? Curator: Difficult to say with certainty. The context suggests an era of societal change, the rise of bourgeois society and a fascination with lineage – though a slightly mocking fascination. This could represent a cheap and accessible attempt to meet a rising public interest, in images and information regarding nobility. The way in which it's assembled suggests that the format itself could have had political connotations. It also has the character of a study. Editor: Absolutely. And its existence challenges our own institutional practices of elevating individual artworks and artists. Is it elevated because we perceive something interesting and historically grounded in it, or because of who it depicts and the way its image reflects the cultural milieu of the era? It speaks to the wider social role of imagery. Curator: True. By examining how it's made and distributed we learn so much. The cheap, reproducible character and medium are integral to how it generates meaning. Editor: A really important observation. Reflecting on Noman’s choices—etching, inexpensive paper—forces us to see how art democratizes the imagery of power through process and public display. Curator: Ultimately, thinking about production adds an intriguing, almost democratic, layer to these princely faces.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.