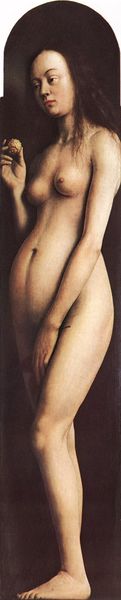

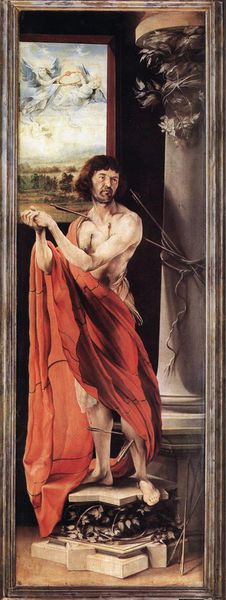

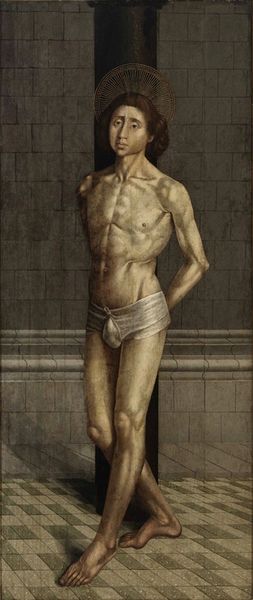

Adam, from the left wing of the Ghent Altarpiece 1429

0:00

0:00

janvaneyck

St. Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

christianity

#

human

#

northern-renaissance

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

portrait art

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Standing before us is "Adam," a panel from the left wing of the Ghent Altarpiece, created by Jan van Eyck around 1429. It currently resides in St. Bavo Cathedral, here in Ghent. Editor: The immediate impression is one of stark realism, a commitment to capturing the minute details of human flesh. But also, there's a raw vulnerability here. The figure is far from idealized. Curator: Exactly. Van Eyck’s oil paint technique allowed for unprecedented detail, shaping the rise of the Northern Renaissance and its focus on observation. What's fascinating is how this hyperrealism challenged pre-existing notions of acceptable imagery in religious art, influencing its patronage and public reception. Editor: And the materiality of oil paint itself is central to understanding the image, the layering creating this uncanny skin tone. It underscores the tangible, almost fleshy reality of the subject matter in ways tempera or fresco simply could not. The very act of depiction becomes a kind of making flesh, doesn’t it? Curator: Absolutely. The choice to depict Adam with such uncompromising realism serves a theological function. By eschewing idealization, Van Eyck highlights human fallibility, the very thing the Altarpiece, as a whole, seeks to redeem. This realism wasn't just a technical accomplishment but a social statement, changing the power dynamics related to who and how people were represented in religious spaces. Editor: I wonder about the labor of it all, though. Imagine the hours spent layering those glazes, grinding the pigments. The skill embedded into this piece goes far beyond mere technical mastery. Curator: Agreed. This focus invites an understanding of artistic work not as divine inspiration but as a physical, materially contingent labor that has its value dictated through cultural institutions like the church, that were its original intended consumer. Editor: Looking closely makes me really aware of just how innovative Van Eyck was for the period. We're forced to confront the awkward, imperfect human body rather than an ethereal ideal. Curator: Indeed, and by doing so, he set in motion a significant shift in the way we perceive and portray humanity, the ripples of which can still be felt today. Editor: Well, considering it, this piece has shown me the potency of artistic creation to be deeply bound up with labor and consumption—it is fascinating.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.