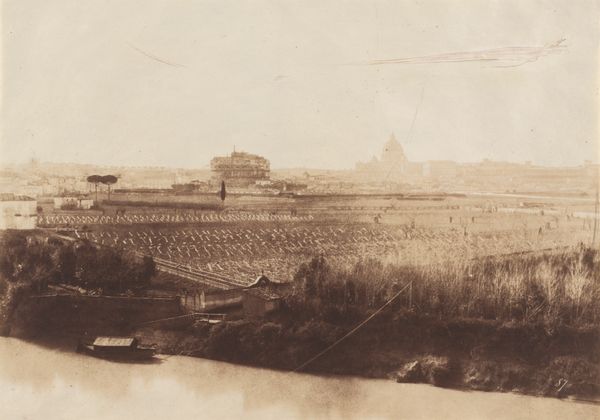

Top of the Wall From Anting Gate, Pekin, Taken Possession by English and French Troops, October 1860 1860

0:00

0:00

photogram, print, photography

#

photogram

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

Dimensions: image: 23.5 × 29 cm (9 1/4 × 11 7/16 in.) mount: 24.8 × 31.1 cm (9 3/4 × 12 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This unsettling image shows the "Top of the Wall From Anting Gate, Pekin, Taken Possession by English and French Troops, October 1860," a photogram print by Felice Beato. It immediately evokes a sense of desolation and domination. What stands out for you? Editor: The sparseness, definitely. The emptiness is punctuated by those austere flagpoles lined up in the center. There is an overwhelming visual weight to that single element of forced control. Curator: Indeed. The verticality of the poles presents such stark symbolic intent in the flat horizontal composition of the captured wall. This emphasizes the occupying presence and the transition of power. You know, it is an Orientalist work from a turbulent period. What do you think about its historical weight? Editor: The image itself becomes a historical document, solidifying the narrative of Western powers imposing themselves on China. The medium of photography, relatively new at the time, adds a layer of "authenticity," although it's clearly a carefully constructed and selected vantage point. Curator: You’ve hit the core there! What is so significant about the flag? Flags have been flown across history. As visible assertions of control over captured landscapes, what do the visual signs suggest in that symbolic vertical composition that intersects so aggressively into the visual of Chinese heritage? Editor: The image also implies something lost, not just visually but culturally. Think of how Beato selected his subject. This visual representation served to propagate an empire-building mindset. How it impacted the populations through visual media is thought-provoking. Curator: It certainly speaks volumes about how cultural memory and power intertwine, in both grand historical narratives and deeply personal experiences of that time, and later times, as photographic images reproduce their meaning. What else can we interpret? Editor: For me, beyond its immediate historical context, the image serves as a reminder of how photography can be used both to document and to manipulate narratives of power. It really invites critical engagement. Curator: Absolutely. A stark, potent reminder that visual representations carry their own heavy legacy. It reminds us to approach these images with an acutely critical gaze, and recognize how complex symbols have transformed from then to now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.