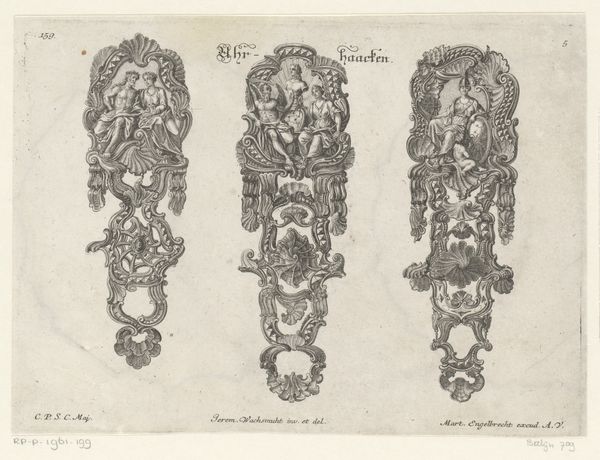

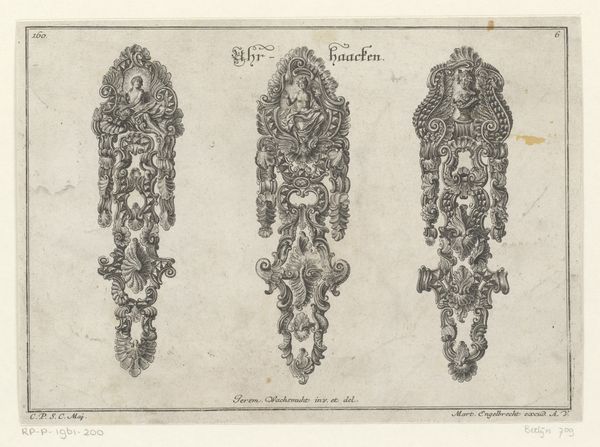

print, engraving

# print

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 163 mm, width 241 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

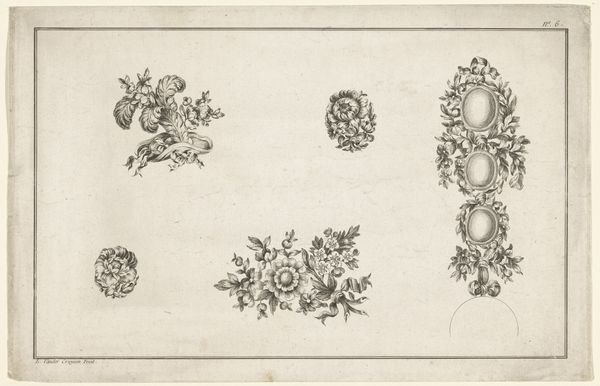

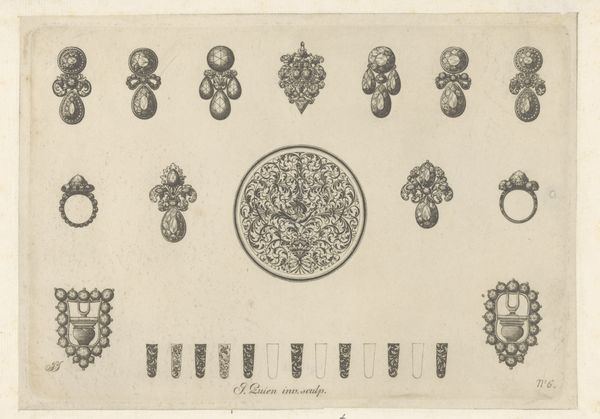

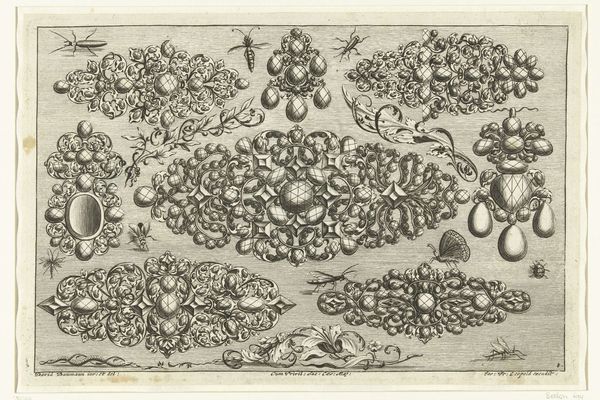

Curator: My eye is immediately drawn to the level of ornate detail! Editor: And what we’re looking at, precisely, is an engraving from 1762 titled *Brooches, Buckles, Earrings, and Rings*. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. The artist is Jean Guien. Curator: Thank you. It has an otherworldly feel. It is as though I am observing a diagram detailing ornaments for some fantastical being of royalty from folklore. Editor: This image allows a view into the visual culture and political semiotics of the period, reflecting how jewelry functioned in asserting status and displaying wealth. Engravings like these weren't simply aesthetic exercises. They helped to circulate specific ideals, offering designs and aspirations, especially for emerging elites who seek recognizable emblems to affirm authority. Curator: Right! And notice the positioning of the crown, dominating the other pieces. The jewels that look like tears that the crown rests upon gives an empathetic narrative, but also subtly projects European hegemony across the graphic landscape. Editor: These weren't innocent objects; consider how such displays often relied on exploiting labor, gaining wealth through dispossession—luxury constructed on social injustice. And let us consider its institutional presence; placing Guien's print within the larger history of how decorative arts have often been relegated, perceived as "lesser" than other forms of artistic expression and how its production mirrors historical biases related to artistry and societal contribution. Curator: Precisely! Seeing it as simply ‘decorative’ is an injustice! Looking at the distribution, each element is arranged thoughtfully so that its accessibility doesn't intimidate the rising classes from adapting components to their own tastes, allowing it to subtly infiltrate new visual contexts, further blurring already complicated intersections of identities. The jewelry here acts like propaganda—a very effective dissemination tool. Editor: Agreed. Its graphic reproducibility is key; an engraving allowed the circulation of designs, expanding influence beyond immediate access, playing into consumerism, while concurrently instilling aspirational values aligned with hierarchical systems of control. Curator: Thank you, this has really shed a different light on things for me. Editor: And to me as well; always rewarding to look at art this way.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

The name of this French engraver working in London is known only from this series of designs, which was first published in 1710. The rapidly changing fashions made it no longer worthwhile for designers to publish their jewellery designs. Sources include complaints by goldsmiths that they depended chiefly on the size of the gemstones their clients brought them.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.