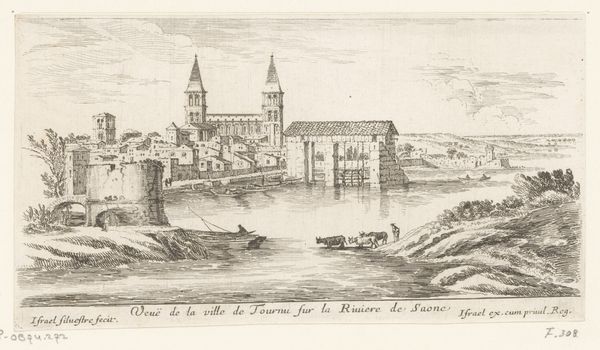

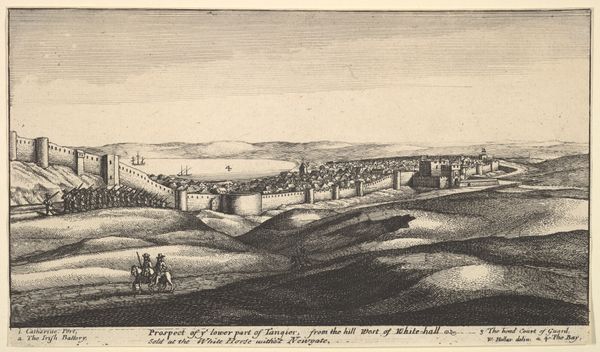

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 2 3/16 × 4 9/16 in. (5.5 × 11.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Wenceslaus Hollar’s “Cannstadt,” created around 1665, offers a captivating look at this German town in the Baroque period. It's rendered meticulously as an etching, demonstrating Hollar's skill in capturing topographic details. Editor: There’s a wonderful stillness to it. The tones are subtle and muted, which adds to a kind of pastoral feel, even though it is undeniably an urban scene. The repetition of lines forming textures in the trees, buildings, and the sky provides overall cohesion. Curator: Hollar was, above all, documenting places undergoing immense transformation. His cityscapes—and there were many, he meticulously recorded London before and after the Great Fire—became vital records for understanding urban development. The commercial activity suggested here speaks volumes about Cannstatt's emerging importance. Editor: True. From a formal standpoint, I'm struck by the composition. The waterway bisects the space and becomes the stage that permits two figures on horseback to travel into our view, subtly leading the viewer’s eye towards that detailed skyline in the background. Curator: Consider, too, the significance of printmaking at this time. It was a democratizing force. This was before photography, and Hollar’s prints allowed a wider audience access to images of far-off locales and served various purposes, including documenting the progress of architectural and urban development. He was essentially offering a glimpse into a specific reality accessible for educational and political goals. Editor: The very controlled, parallel strokes that create this image draw my attention as well. Notice how Hollar utilizes simple and even understated mark-making conventions that transform simple strokes into landscape, architectural, or even textural planes. Curator: It's incredible to consider the precision and the skill required to produce something this detailed by hand in an age lacking photography. One must recognize that prints had tangible political and financial capital for publishers and also the sitters and/or locales reproduced. This print acted as a visual contract between the artist and those represented in the print. Editor: Absolutely. The image presents, structurally, so many sophisticated design components: The repetition and variation in linear organization—like hatching and cross-hatching—build out that rich and deeply developed field of value. These features construct and unify Hollar’s vision into an undeniable whole. I come away with an intimate vision of early industrial Germany and of Hollar’s great etching ability. Curator: Yes, considering this work reminds me of the broader circulation of imagery and knowledge in the 17th century and its implications on our understanding of space and place. It enriches our experience, connecting it to the socio-economic context of its creation and reception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.