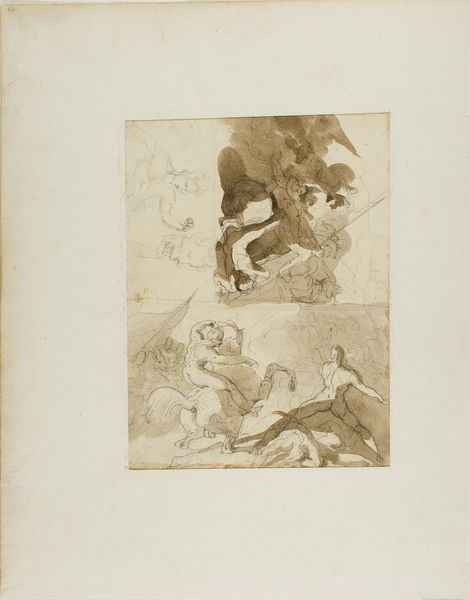

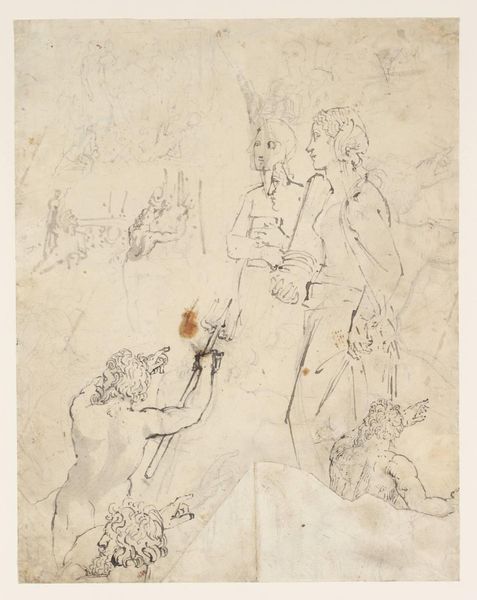

drawing, paper, watercolor, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

ink

#

academic-art

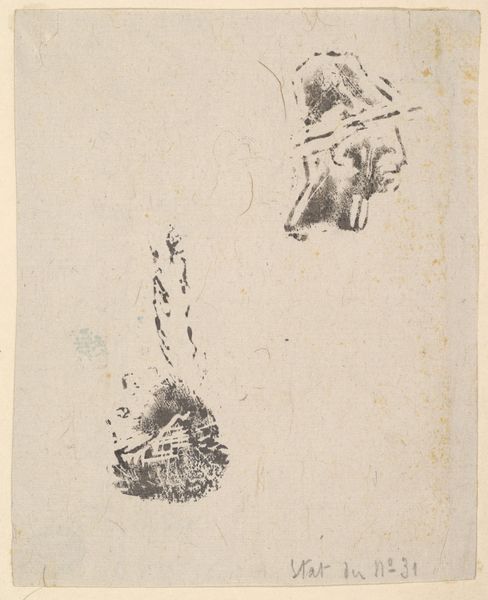

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 148 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a collection of hands and feet! These disembodied studies seem like anatomical fragments adrift on the page. Editor: It’s initially a bit unsettling. I mean, we are immediately confronted with disconnected body parts. There is a historical implication to this fragmentation. The power structures implicit within a society have always determined whose bodies are valued whole, and whose can be cast aside. Curator: Absolutely, and considering this drawing, “Hands and Two Soles of Feet,” comes to us from the period of 1650 to 1750, an era steeped in the burgeoning scientific gaze and colonization, one might read into this artistic exercise ideas about objectification and classification of racialized individuals' anatomy and physicality. Editor: I am completely in accord! Moreover, the artist employs ink and watercolors on paper, which renders a delicacy and ethereality, an exercise of technical skill that reinforces an approach where detachment can serve both creative and objectifying purposes. But whose hands? Whose feet? Where are their bodies? And why have they been cut off? These are not mere idle queries. Curator: Though anonymous, the artist captures the gestures in a way that feels both meticulous and slightly unsettling. Editor: Their precise portrayal contrasts with the absence of the subjects to whom these hands and feet belonged, thereby amplifying, to my eye, the silent protest inherent in the body's depiction—or dissection—as passive material. Even in studies like this, art implicates our relationship to the human figure. Curator: What interests me about that perspective is how a collection of hands, and yes, even feet, might be symbolic on an emotional level. In many traditions, hands represent agency, connection, or work, and here, they float, severed from these roles, becoming abstract symbols themselves, almost begging for connection. Editor: Your mention of "work" and the implied act of creation evokes a powerful contrast with the colonial context in which the work was produced, prompting one to contemplate: Who is truly empowered to 'work' or create freely? Are these depictions truly studies, or evidence of enforced passivity? Curator: I hadn't thought of the enforced passivity implications, but it adds such depth to the work! Editor: And so the artist’s anonymous exploration compels a continuing conversation, demonstrating the undeniable resonance of our anatomies and their intrinsic capacity for historical meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.