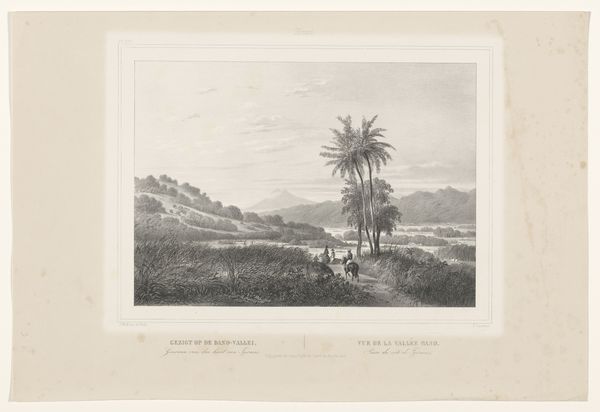

Dimensions: height 265 mm, width 363 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

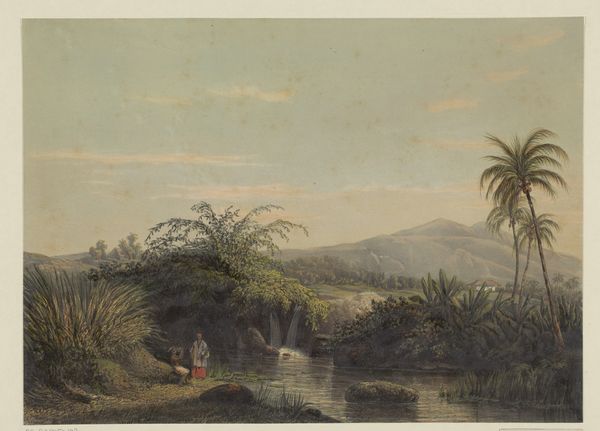

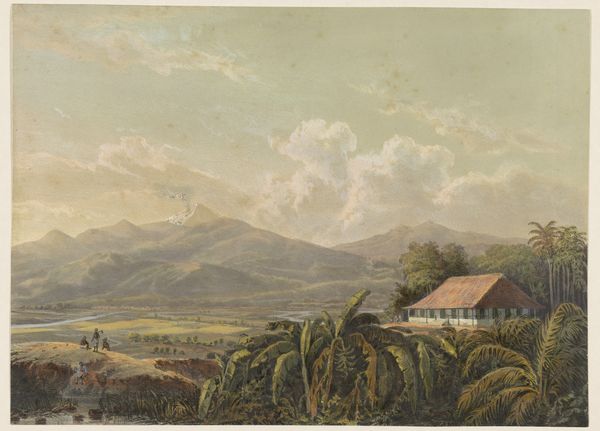

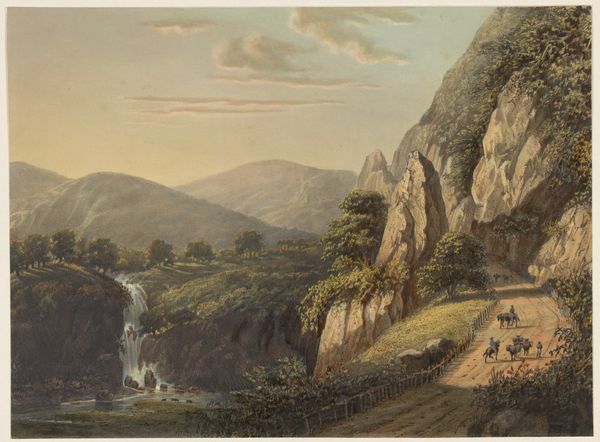

Curator: My initial response to Johan Conrad Greive's "View of a Road to the Salak Valley in Java", created in 1869, is one of serene detachment. The use of watercolor lends a light, almost ethereal quality to the landscape, softened by a sense of idyllic exoticism. Editor: It does strike me as a somewhat romanticized view, yes. It’s crucial to contextualize this artwork within the landscape of Dutch colonialism in Java. Greive, although likely never having visited Java himself, represents it through the lens of imperial power. Who benefits from such an idyllic view? Whose labor creates this apparent paradise? Curator: Precisely. But formal elements remain important here. Notice the composition – the winding road draws the eye deep into the valley, with strategically placed native huts providing both scale and a visual entry point for the viewer. How might one understand these framing devices in terms of an organizational logic specific to representational strategy? Editor: The light itself serves a crucial purpose here. It softens the potential realities of the colonial project while accentuating a supposed harmony. Even the figures on horseback are mere suggestions; not active players in any kind of meaningful representation. It all promotes the European gaze, positioning Java as passive, receptive to western control. What is strategically revealed or, crucially, concealed. Curator: Absolutely. Considering the conventions of the picturesque that pervade the composition, it almost seems a carefully managed 'nature'. Editor: It brings up an uncomfortable juxtaposition, that’s certain. Art produced during colonization isn't neutral, is it? The role of landscape art here is often overlooked as subtle forms of justification and ideological reinforcement of power dynamics. Even watercolor, with all its delicacy and translucence, is burdened. Curator: These visual markers—softened light, harmonious color palettes, serene compositions—often serve to elide or even obscure the underlying realities of control, creating in its place an inviting simulacra to those who possess the ability to access the landscape, physically, visually, or ideologically. Editor: It underscores just how imperative is it that contemporary art theory continually interrogate such works and the role they play not merely as depictions but also as enactments of power. Curator: Yes, engaging with art’s complexities—a beautiful reminder.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.