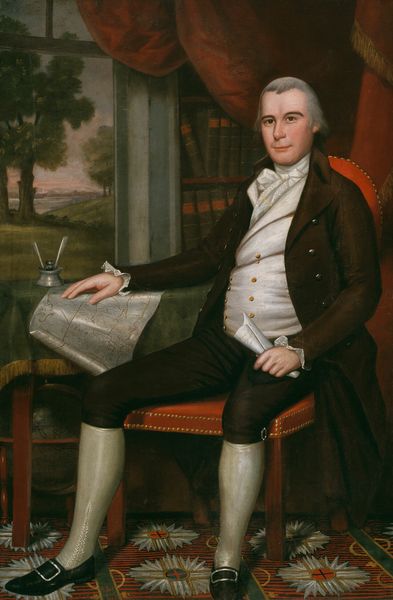

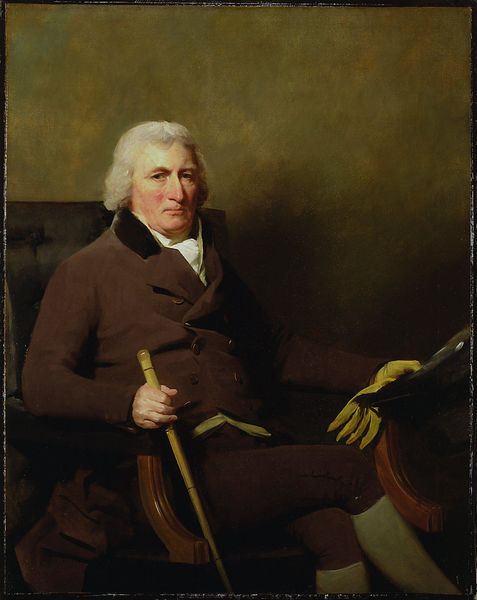

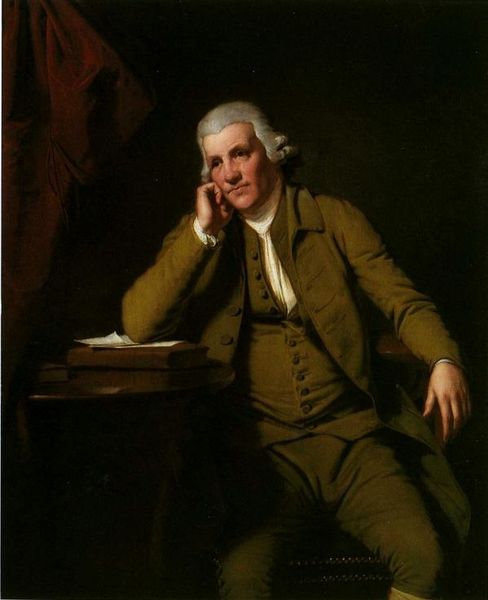

painting, oil-paint

#

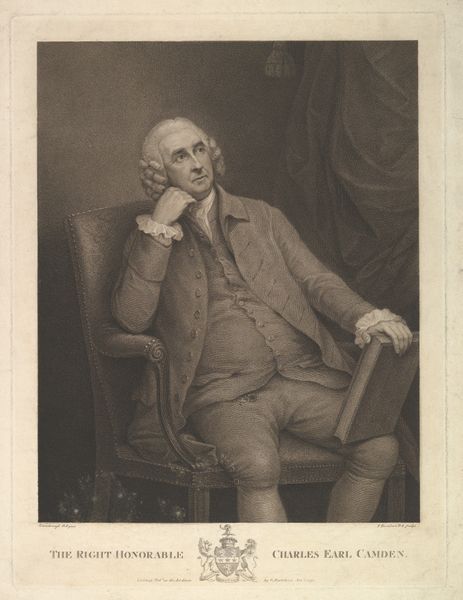

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 18 3/4 x 14 1/2 in. (47.6 x 36.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This painting, housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is William James Hubard’s depiction of “Charles Carroll of Carrollton.” Painted in oil sometime between 1827 and 1830, it presents a thoughtful portrait of its subject. Editor: My first impression? The overwhelming darkness makes me feel a bit melancholy. But then my eye catches the sheen of the painted fabric. Hubard did an incredible job with texture. Curator: Indeed. Carroll, as you may know, was the last surviving signatory of the Declaration of Independence. Consider the implications: Hubard paints this icon toward the end of his life, amidst shadows, a suggestion, perhaps, of fading light? It’s potent stuff, heavy with history, wouldn't you say? Editor: I immediately wonder about the canvas, the preparation. Did Hubard source materials locally? The pigments too! Look at the blacks-- what minerals and processes yielded that depth? This painting reminds us that history is embedded in material choices. How fascinating! Curator: Absolutely. It's all very tangible, isn't it? Those whites and reds, just luminous against the encroaching darkness. As a Romantic portrait, I’d say that Hubard focuses on presenting the man and his humanity...a soul ready to be judged, perhaps. Editor: I’d argue the academic style really emphasizes a level of distance. What's depicted over here on this desk feels significant: those quill pens poised to write and those books. I like to imagine the socio-economic implications of all of this, what their physical presence represents about this man. It begs the question of how literacy and the tools of writing have evolved in the making of society. Curator: I like how you think. It invites the viewer to ponder who controls the means of symbolic production! Still, that shadow to the left—does that darkness suggest a storm? Or simply time passing? Hubard really lets the composition do the talking, and invites us to imagine that darkness however we need. Editor: Maybe the shadow reminds us that portraits like these served a material function too. They were displays of wealth and status, traded as commodities and enjoyed by wealthy families like this one. To understand its worth, you've really got to question not just how the thing looks, but what purpose the image had in society! Curator: Agreed! The play between the figure and the atmosphere offers layers upon layers to consider. It’s difficult to ignore, don't you think, what remains unspoken in this image of a monumental figure! Editor: Thinking about the artist, his labor, materials and the historical setting—that’s where the narrative truly takes hold for me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.