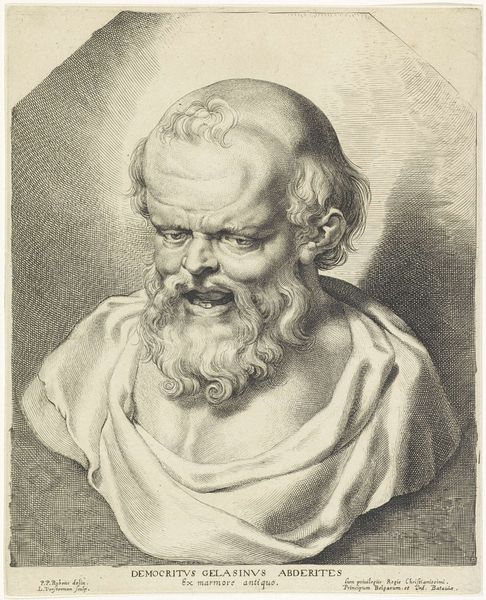

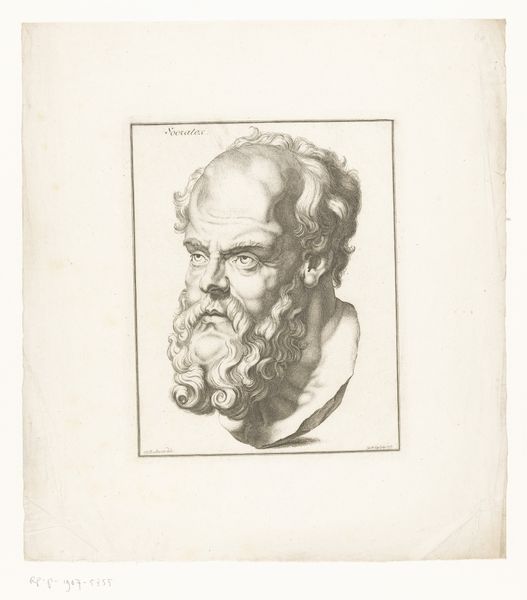

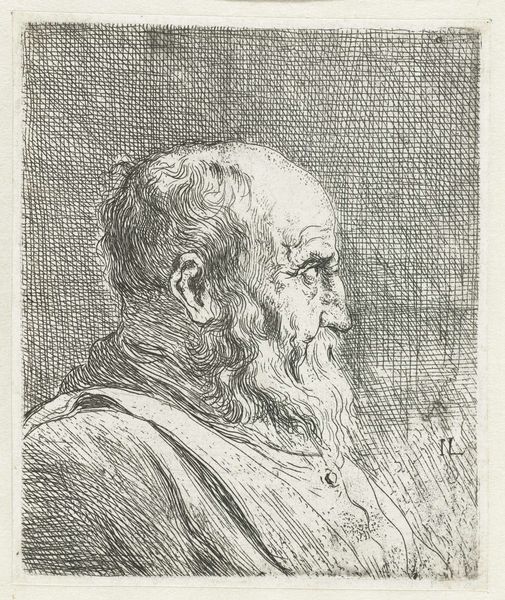

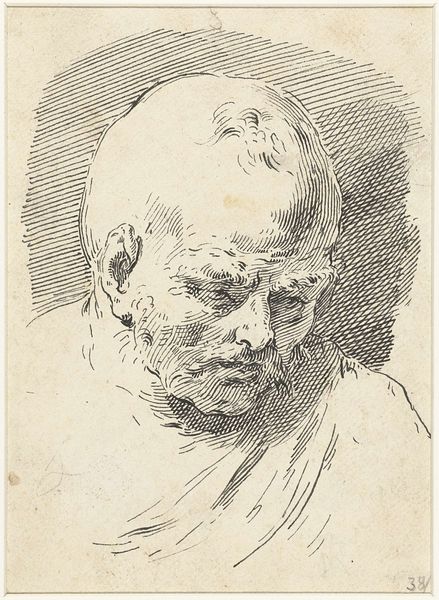

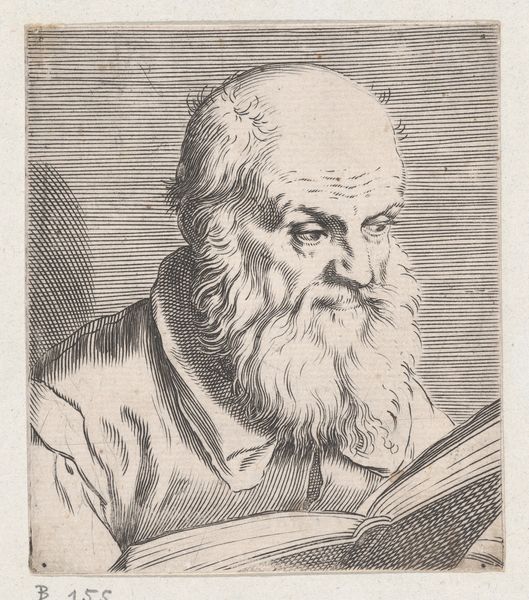

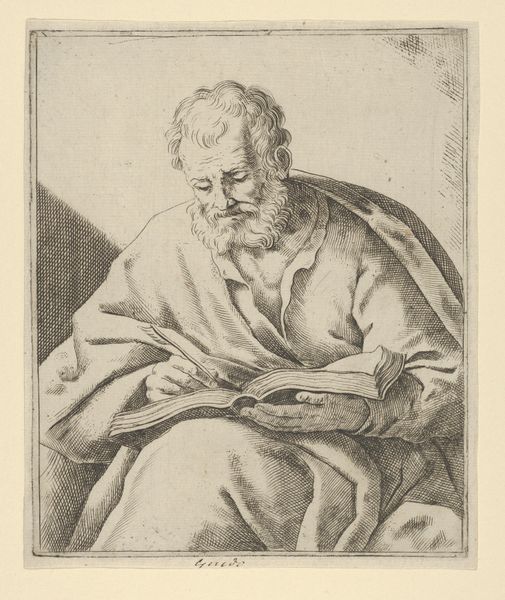

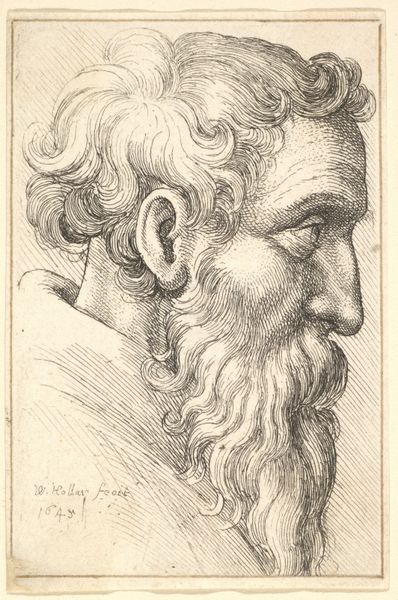

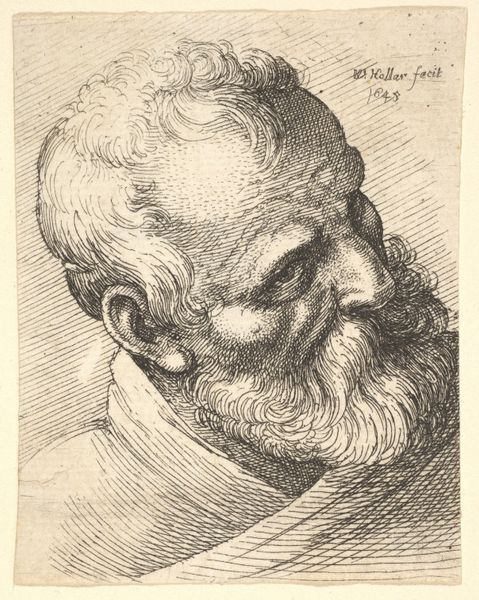

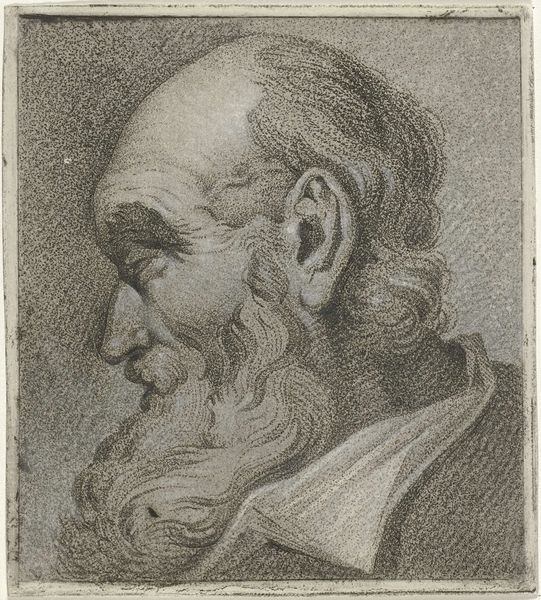

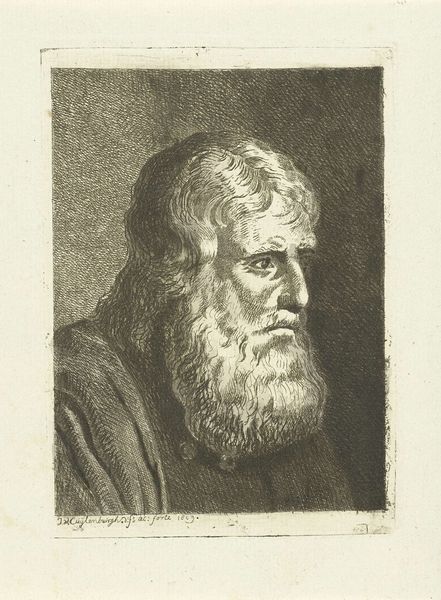

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 170 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jan de Bisschop's engraving, "Portretbuste van Democritus," dating back to the late 1660s. The detail achieved through the engraving is amazing, especially considering the relatively small scale. What strikes me is how this image revives a classical sculpture for a new audience, connecting them to ancient philosophical traditions. How do you interpret the role of prints like this one in disseminating classical knowledge at that time? Curator: That’s a key point. In the 17th century, prints were vital for circulating images and ideas, especially regarding classical antiquity. Think about the power dynamic: Who had access to actual Roman sculptures? Usually, just the wealthy elite. Prints, however, made classical imagery accessible to a much wider audience. De Bisschop's engraving not only copies a sculpture of Democritus, but participates in shaping and democratizing the knowledge of classical figures. What does it mean that a philosopher known for his atomic theory is rendered here in such a durable, seemingly permanent, artistic form? Editor: That’s fascinating! It’s almost as if the engraving is trying to grant him a kind of immortality through art. So the print serves as both documentation and a form of cultural capital. It is also interesting that the writing states "Democritus . ex marmore antiq", can we assume it's copied from antique marble? Curator: Exactly. Moreover, the choice of Democritus isn't random. He was a pre-Socratic philosopher associated with materialism. The rise of the printing press and its ability to reproduce and distribute texts and images coincided with the reformation of thought, like the growing emphasis on scientific empiricism. Did the proliferation of printed images showing thinkers of the past also legitimize the values of these new scientific attitudes? Editor: I see! So this seemingly simple portrait becomes a powerful vehicle for shaping cultural values and disseminating classical learning through a rapidly evolving media landscape. Curator: Precisely. These images, even copies, played a key role in constructing and disseminating a specific historical narrative. They weren't neutral reproductions, but active participants in shaping how people understood the past and, ultimately, the present. Editor: Thinking about that now gives me a whole new appreciation for prints as cultural objects, not just copies! Thanks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.