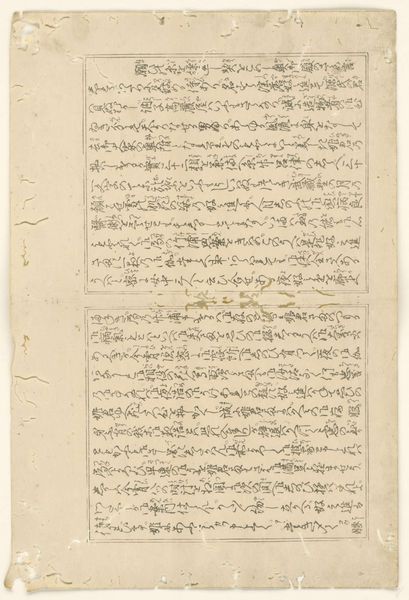

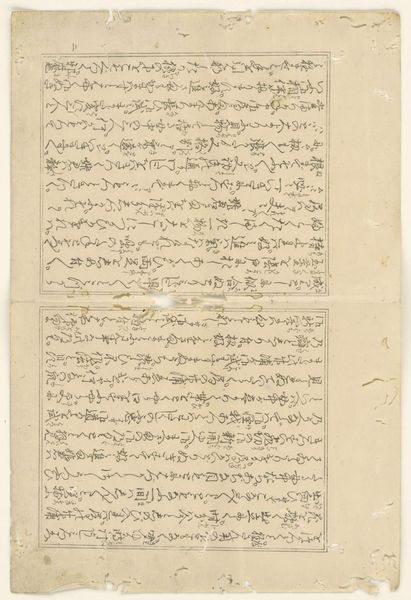

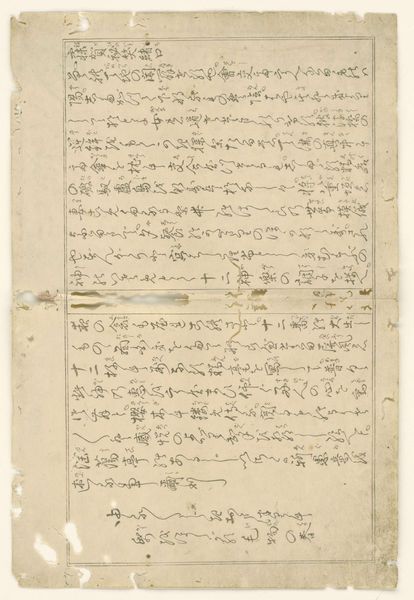

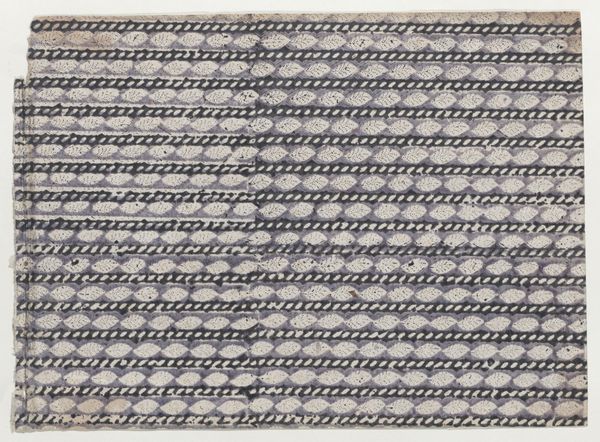

print, paper, ink

#

narrative-art

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

paper

#

ink

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: height 254 mm, width 381 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

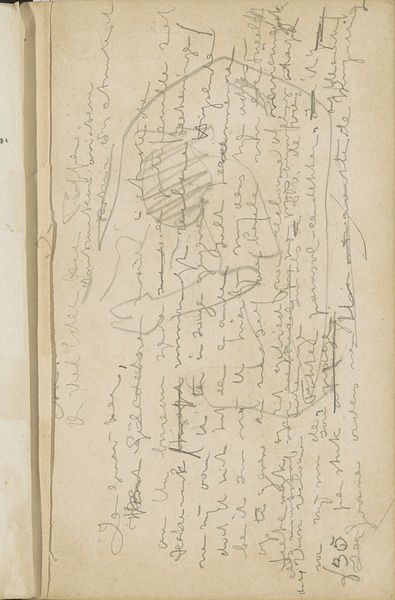

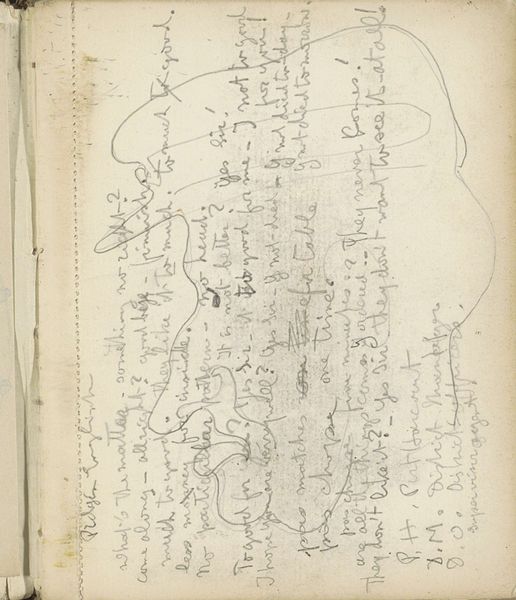

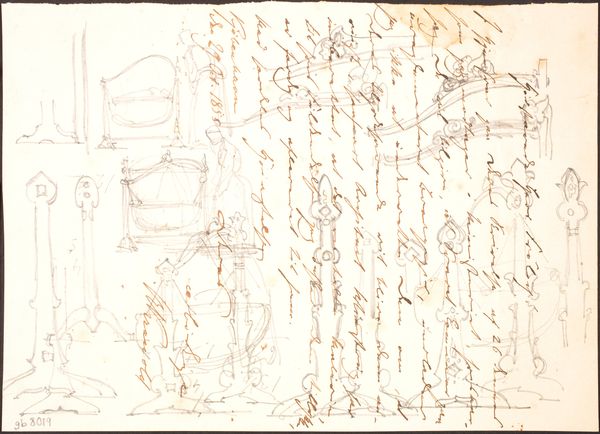

Curator: Before us we have a print titled "Tekstblad van Negai no itoguchi", crafted by Kitagawa Utamaro in 1799. It's ink on paper, and part of the collection at the Rijksmuseum. It presents, primarily, a page filled with elegantly brushed Japanese calligraphy. Editor: My initial impression is one of intimacy. The aged paper and delicate lines speak to something private and personal. The tight registration gives an overall somber feel to the page. Curator: Indeed. The text itself plays a significant role, suggesting a form of personal narrative. One could easily surmise a personal dedication based on the visual structure. There's an inherent power in handwritten text, revealing an individuality and personality. Editor: Especially at the close of the eighteenth century. I’m struck by the level of artistic skill applied to what seems, at least from this distance, like a practical, quotidian document. How do these prints fit into the broader cultural context of the ukiyo-e tradition? Curator: Precisely. Utamaro, as a master of ukiyo-e, was deeply invested in conveying the subtleties of human expression. And this sheet—as a narrative artwork—would very likely be accessible to the bourgeois culture in Edo. Utamaro helped refine an entire mode of art, taking traditional art toward modern art forms. In this context, this piece presents a dialogue, an effort to both preserve tradition but also make it readily available in an easy-to-carry manner. Editor: This tension between individual expression and the democratization of art really strikes me as key. Was the artist well-regarded among contemporaries, or has this prestige increased over time, do you think? Curator: While certainly famous, Utamaro's reception also involved censorship during his time for portraying powerful political figures in ukiyo-e form. I see his willingness to engage with popular culture not as a degradation of artistic ideals, but instead as part of an important contribution in Japanese culture. Editor: What a paradox - art becoming popular and then suppressed. So it appears his ability to capture and condense larger social or cultural trends into visual language is key. Curator: Indeed, it represents a dynamic period where societal and political realities significantly shaped artistic creation. Editor: Thank you—a unique meeting of personal and public expression in this seemingly simple, elegant page. Curator: It seems we find ourselves at the threshold between private dedication and a form of socio-political record of late-eighteenth century Japan.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.