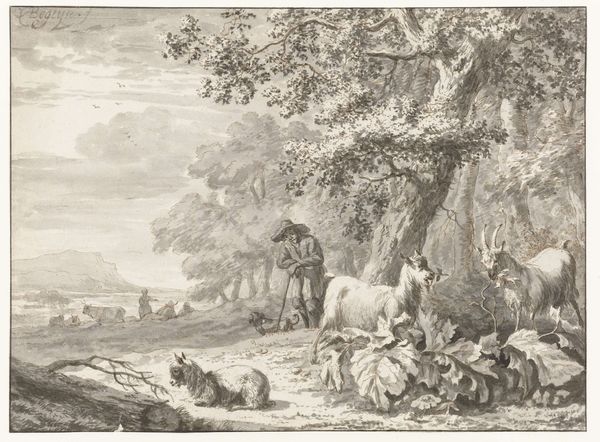

Dimensions: height 154 mm, width 230 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Ferdinand Ernst Lintz's "Gurth the Swineherd and Wamba the Jester," a graphite drawing on paper made sometime between 1843 and 1909. It feels very…staged? Like a tableau vivant, but also really still and quiet. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see the enduring power of archetypes. Look at Gurth, the swineherd – he embodies a connection to the land, to a simpler, perhaps idealized, past. Then we have Wamba, the jester, forever caught between worlds, between seriousness and light-heartedness. Editor: What do you mean by "caught between worlds"? Curator: Well, consider the jester's role historically. He's allowed a certain freedom of speech, a subversive voice within the court, but he’s also marginalized. His symbols – the bells, the motley – set him apart, reminding everyone of his liminal status. Here, he blows his horn. Is it a call, a warning, or simply noise? Editor: I guess I hadn't really thought of them as symbols, more just...characters. The pigs add to that feeling, they seem more real than the figures, somehow. Curator: Exactly! Even the swine take on a symbolic weight. The domestic pig, descended from the wild boar, representing both sustenance and untamed nature. Lintz places them so deliberately. Think about how pigs have been portrayed throughout history. Do they seem threatening here, or comforting? Editor: Comforting, I think. Maybe a little melancholic. The muted tones really add to that. I never would have thought about them carrying that much meaning! Curator: That is the joy of iconography, isn't it? Seeing how images build meaning over time. Hopefully you will use it to your advantage in your field!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.