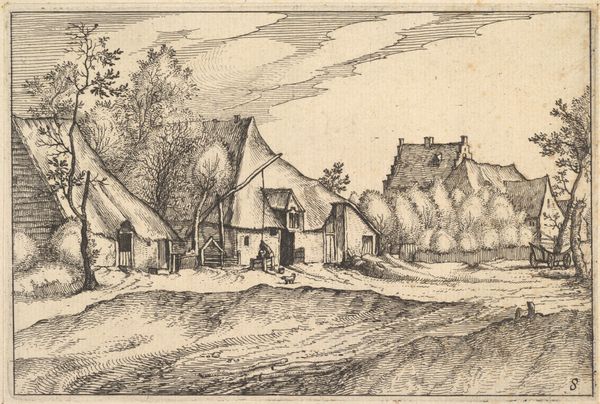

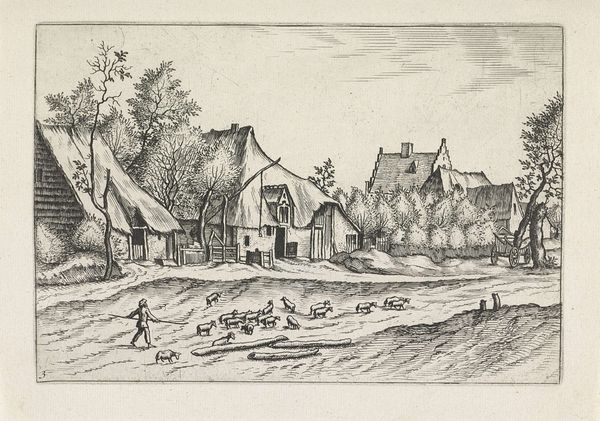

Village Road, plate 3 from "Regiunculae et Villae Aliquot Ducatus Brabantiae" 1605 - 1615

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, pen, engraving

#

drawing

#

pen drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

pen

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 4 1/8 × 6 1/4 in. (10.5 × 15.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

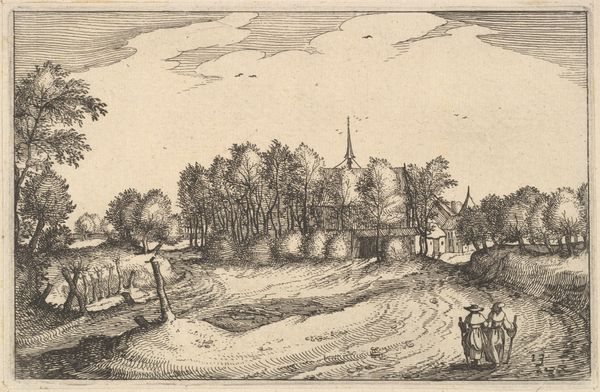

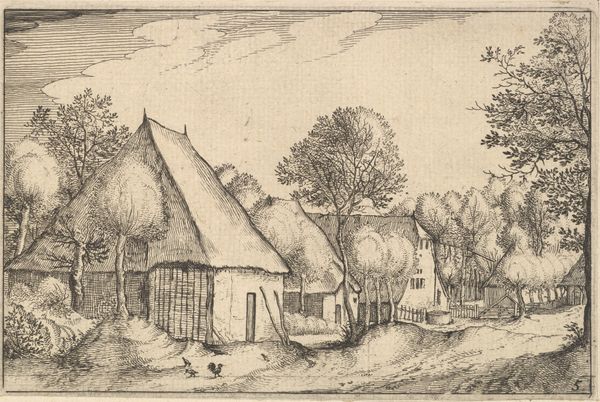

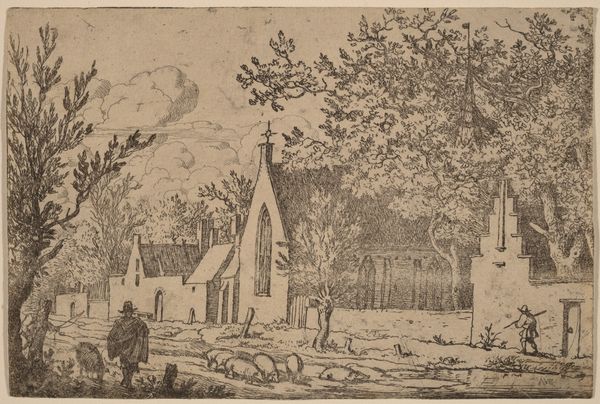

Curator: Before us, we have "Village Road, plate 3 from 'Regiunculae et Villae Aliquot Ducatus Brabantiae,'" an engraving by Claes Jansz. Visscher, dating roughly from 1605 to 1615. Editor: It’s incredibly detailed! There’s a tangible sense of rustic simplicity. You can almost feel the grit of the road beneath your feet and smell the hay drying on those roofs. Curator: The print belongs to a series showcasing rural scenes, which places it within the historical context of a shifting relationship with land. Think of the rising merchant class, land ownership, and nascent capitalism shaping artistic representations of the countryside. Editor: Absolutely. Looking closely, one sees the meticulous labour involved in crafting such an intricate image using the engraver's tools and craft knowledge. Each line represents countless hours of work—it speaks of a dedication to documenting the landscape in an age before photography. How interesting that he decided to produce several images to become a series! It feels like documentation labor. Curator: That's precisely it. Consider, too, the socio-economic status of those depicted here. The scene likely represents the lives of tenant farmers or labourers; their stories become visible, if only in the margins, resisting a purely idyllic interpretation of the landscape. Their toil made those wealthy dutch landscapes real, their relationship to ownership being represented there as absent. Editor: And there's the matter of consumption. Who was buying and viewing these prints? Wealthy merchants who would have these hung in their homes? And, therefore, reinforcing a very specific lens by which these people were seen? Curator: A key point. These prints potentially catered to an urban elite keen to consume idealized images of the countryside, reflecting, perhaps, a romanticized notion of rural life in contrast to their own lived experiences in the burgeoning cities. The image, in this light, is a form of cultural capital. Editor: Indeed, the materiality of the print itself—the paper, the ink—speaks to broader economic structures and networks of trade within the Dutch Golden Age. The materials were just another important component of it! Curator: It truly makes you consider the labour of landscape in relation to the Dutch economy and the colonial powers abroad and back home. It speaks to the many intersectional relations involved. Editor: The engraving prompts a further exploration into the means of its own making and its place in the domestic economy, an exploration into craft and materiality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.