Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

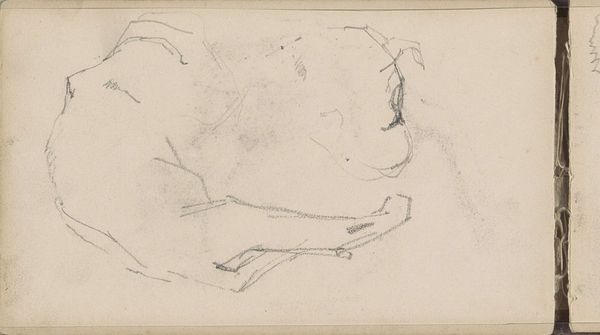

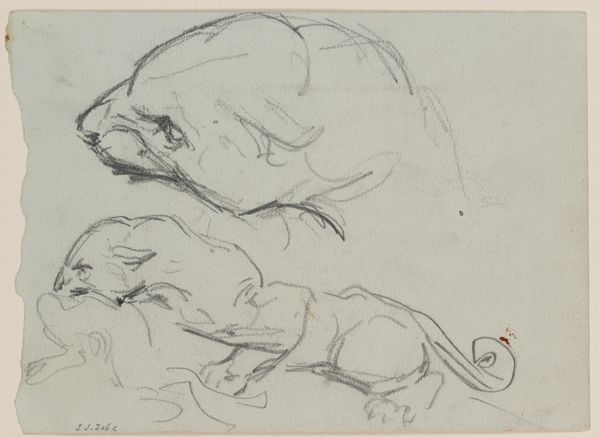

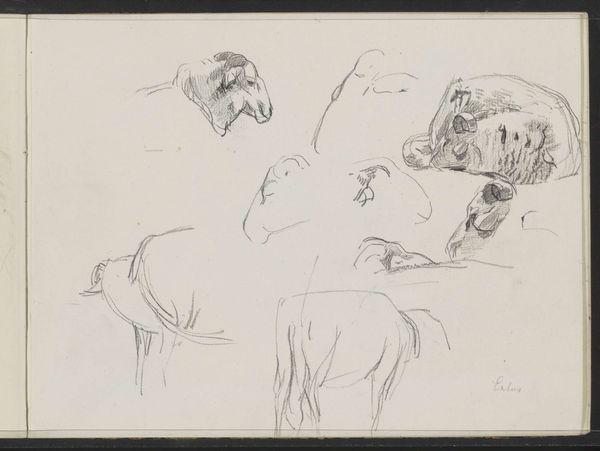

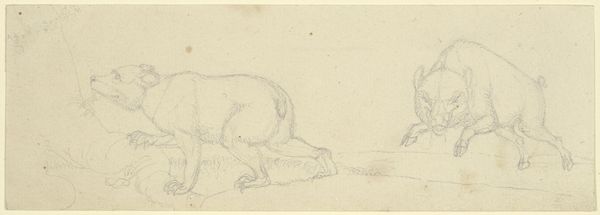

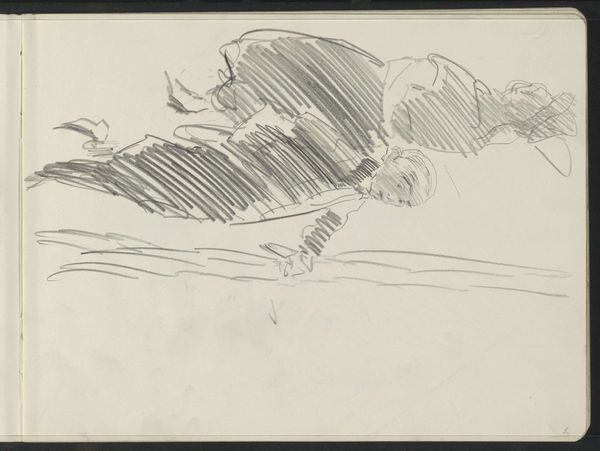

Curator: There's a disarming simplicity to this pencil drawing; almost like a fleeting thought captured on paper. Editor: I see that immediately. It’s the economy of the lines; the work has an immediacy. What can you tell me about the artwork itself? Curator: This drawing, "Path in a Heath Landscape and a Man with a Hat", is by Johannes Tavenraat. Created sometime between 1842 and 1868, it uses delicate pencil work to depict a tranquil scene now held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. It speaks to the Romantic ideals prevalent at that time. Editor: Ah, Romanticism – a period fascinated by nature and the sublime. What is it about the symbolism here, though, that carries an emotional weight across time, even without any grand display of the sublime? Curator: Perhaps it’s the recumbent figure, the man resting – possibly sleeping – in the landscape. It’s a posture of surrender and merging with nature itself. The figure echoes a shepherd in classical iconography; mankind subsumed within nature's grandeur. The heath landscape itself represents a specific kind of untamed nature that offered solace for burgeoning urban populations. Editor: So the work hints at a deeper dialogue about man’s relationship with nature and progress within society? The lone figure certainly prompts consideration, and a reflection on how the artist viewed social norms during that era. Were representations of solitary figures common during this time, and did this pose particular political sentiments through its social commentary? Curator: Solitary figures became a prominent symbol during the 19th century, particularly during the rise of individualism and an increase in feelings of alienation caused by industrialization and modernization, which suggests a retreat inward towards nature. Here, it’s the path itself that's important, a sort of pilgrimage back to natural ways of being that have roots dating to antiquity. Editor: I'd have never thought the "return to nature" archetype that exists so frequently now would have such deep origins. I think what makes the piece resonant, even now, is its understatement. It does not try to awe; rather, it whispers. Curator: I completely agree; that’s the true charm.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.