painting, plein-air, oil-paint

#

sky

#

painting

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

impressionist landscape

#

oil painting

#

seascape

Copyright: Public domain

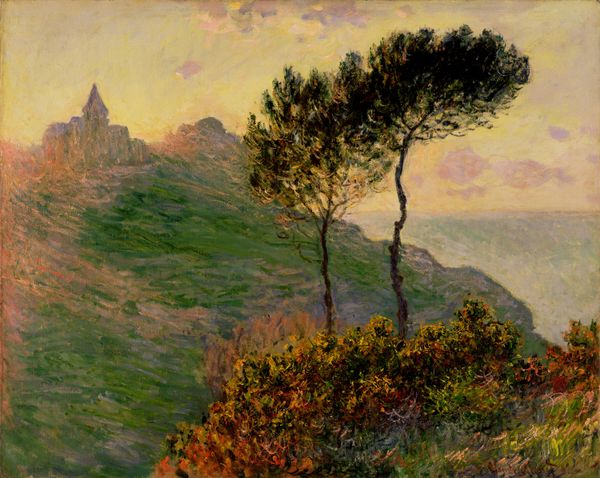

Curator: This is Claude Monet's "The Church at Varengeville and the Gorge of Les Moutiers," painted in 1882. He used oil on canvas in the plein-air style to capture this landscape. Editor: It strikes me as a somewhat melancholic scene, the subdued blues of the sea and sky meeting those muted greens and golds in the foliage. There's a sense of the vastness of nature against the backdrop of that tiny church clinging to the clifftop. Curator: Absolutely, and considering Monet’s frequent moves around this period, often seeking out very specific light and weather conditions, it’s compelling to think about the material constraints he encountered while actually producing this. The transport of the easel, the paints, the very act of confronting the wind—it's all embedded within those brushstrokes. Editor: Right, but let's also consider that this is more than just a picturesque scene. Monet, throughout his career, engaged with the rapidly changing socio-political landscape of France. We see this in his focus on everyday life, and it's critical to understand the rise of seaside tourism during this period, along with the increased visibility of working-class communities. Curator: You're leading into a compelling angle: we often view Impressionism through a lens of idyllic leisure, overlooking that Monet himself was very much involved in the daily labor of *painting*, the mixing of pigment, stretching the canvases; these aspects are often sidelined, making it easier to romanticize the lifestyle of an artist detached from tangible production concerns. Editor: And even this depiction of a seemingly tranquil landscape conceals complex relationships, I believe, in land ownership and usage. These scenes were increasingly commodified through art, and how that act participated in the marginalization of rural communities, these realities need reckoning. It challenges the sanitized perception of this painting to delve a little into the economy behind such landscapes. Curator: Indeed, what’s really useful is how Impressionism reveals these tensions by almost drawing attention to the ephemerality of production and materials. His short dabs and visible brushstrokes are the end result of a very particular, physical undertaking that makes all of this art possible. Editor: Precisely! It forces a questioning on our part, to what we consume and, critically, who is excluded from partaking and whose reality is obscured or outrightly erased within a canvas. Curator: So, reflecting upon "The Church at Varengeville," it serves as a powerful reminder, maybe less on ideal scenes but more as how deeply social and economic structures interweave, from Monet's atelier up to his landscapes. Editor: And it should force us to look past the beautiful light effects, towards those shadowed spaces in the scene, towards questions of power that art is more than capable to evoke if we allow it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.