Dimensions: height 210 mm, width 275 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

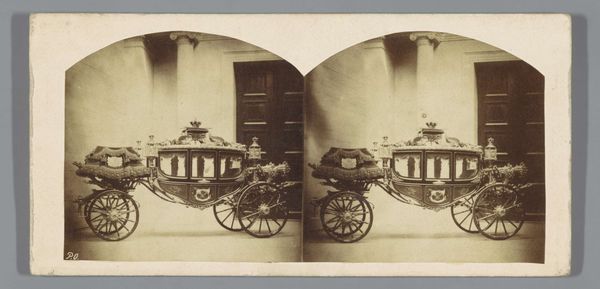

Curator: This albumen print, titled “Koets van Karel X in het Petit Trianon in Versailles,” attributed to an artist only known as “X phot.” and created sometime between 1870 and 1890, immediately strikes me. There’s a subdued elegance, even with such an elaborate subject. Editor: Yes, it feels like faded grandeur. All that ornamentation, yet rendered in sepia tones – it’s almost mournful. One can almost hear echoes of courtly life silenced by history. What statement might we be making, showcasing relics of a monarchy today? Curator: Well, photographs such as this one played a crucial role in shaping public perception of monarchy and power. This one documents a very specific object from a particular political past in a way that invites scrutiny today. In an era grappling with wealth inequality and power imbalances, how do we interpret these relics of opulence? Editor: I find myself particularly drawn to the way the photographer frames the carriage, almost trapping it within the room. It is a static exhibit; what could have symbolized movement, pomp and ceremony is presented as an almost entomological study. The choice to make this an albumen print seems quite deliberate here. Curator: Indeed. Albumen prints, given their popularity in the late 19th century, allowed for wider distribution, almost democratizing the gaze upon these objects, even if access to them in reality was highly restricted. Further, as a technology, photography played a significant role in archiving the material culture of a period, effectively rendering these items subjects to both historical study and judgment. What did the opulence symbolize? For whom did it speak? What realities were concealed by it? Editor: It's fascinating to consider how photography shifted the dynamics between the observer and the observed, especially regarding power. What once might have been a symbol of absolute authority now stands under our collective gaze, ready to be dissected and understood. The still life aspects lend this artwork an eerie tone of finality. Curator: Absolutely. It's not merely a photograph of a carriage; it's a lens through which we examine the construction of power and the evolving relationship between the public and its symbols. That even something intended as active is forced to be still, perhaps the result of larger cultural forces and pressures. Editor: Well, it's given me a lot to think about in terms of what "genre painting" really means and I like thinking about how an old medium and photographic style is actually suited well for critiquing ideas about inherited wealth.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.