Dimensions: height 329 mm, width 225 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

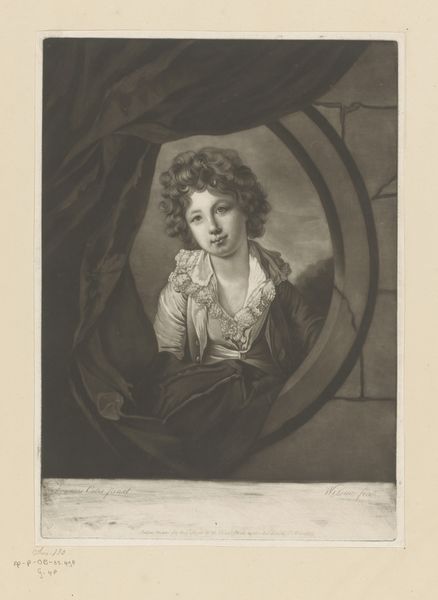

Editor: This is James Watson's "Portrait of Mary Cunliffe as a Child," likely created sometime between 1765 and 1771. It's a pencil and engraving piece. I'm immediately struck by her expression, almost melancholic. The greyhound adds a sense of gentle loyalty. What do you see in this piece? Curator: It's the visual grammar of childhood innocence contrasted with nascent womanhood. Notice the flower crown, a symbol of fleeting purity and virginity, poised atop her youthful curls. The greyhound, more than just a pet, embodies fidelity and nobility, aligning young Mary with aristocratic virtues. The almost classical drapery hints at a staged maturity. Editor: Staged maturity? Could you elaborate? Curator: Consider how portraits, especially of children, functioned in that era. They weren’t just likenesses. They were carefully constructed narratives projecting family status, future prospects, and moral character. What feelings does this contrast stir in you? Editor: I suppose it feels a bit sad. There’s a sense of a performance, or a role that she’s being asked to play. It makes you wonder about the real child behind the portrait. Curator: Exactly! And think about the engraver's skill—the soft shading that renders her skin, the almost photographic detail on the dog. It invites intimacy but also keeps us at a distance. Every line, every choice reinforces a controlled narrative. What will be the impact of all these details? Editor: That makes a lot of sense. It really changes how I view the image, considering all the embedded layers of meaning and purpose. Curator: Indeed. It reminds us that images are rarely simple reflections. They are powerful conveyors of cultural memory and expectation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.